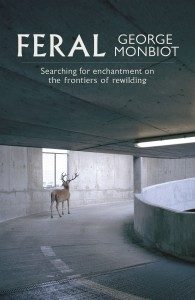

I’ve just been reading a highly recommended book by George Monbiot, the radical British environmental journalist, called ‘Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life‘. I think it’s fair to say that it’s transformed my view of rewilding, making me see important connections between it and the Middle Way. I previously thought of rewilding very much as an extreme romantic fringe of environmentalism. Given ever-increasing human exploitation of the planet, I thought it was a hard enough job even to moderate its effects, let alone throw it into reverse. But Monbiot has made me think again.

Part of the power of his book is revealed by the last part of the subtitle: rewilding is very much about us and our relationship to ourselves, not just about a high-minded focus on the environment for its own sake. The wild is a part of us, not just an aspect of the world, that we repress at our peril. Monbiot does not discuss the neuroscience, but the over-dominance of the left pre-frontal cortex, with its over-confident imposition of order and its endless confirmation bias, is an important aspect of the strained human repression of the wild. He effectively shows its self-defeating nature again and again in his account of our defensive attitudes to wildness in the world.

The over-confident imposition of order tends to neglect the complexity of our relationship with the conditions, and thus undermine our own interests in the long run. Generally, the more inequality of land ownership and the more intense the investment in human uses of the land, everywhere in the world, the more intense the monoculture and the more impoverished the biodiversity. ‘Shifting baseline syndrome’ also means that we have very restricted – localised and temporally limited – standards as to what a ‘natural environment’ looks like. This is especially evident in the highly humanised landscape of the UK, in which, for instance, the utterly treeless sheepwrecked landscape of the Glaslyn ‘nature reserve’ in Montgomeryshire is deliberately conserved exactly like that through continual over-grazing – exactly like the rest of Wales – whilst being described as “the wildest and most regionally important site”. You only need to go back a few thousand (rather than a mere hundred) years to recognise that the ‘natural’ vegetation of most of the UK is temperate rainforest, not overgrazed pasture, but it’s not only sentimental members of the public and the National Farmers’ Union who think otherwise, it’s even some ‘conservationists’.

The particularly perverse example of the British uplands is revealed particularly well by Monbiot, as he shows that the extermination of biodiversity is also so much contrary to even a hard-headed economic assessment of human interests. The bare compacted soil of the green deserts barely retains any water, so after heavy rainfall it is the riverside towns in the plains below that flood as a consequence – but the links between sheepwrecking and flooding are barely discussed. The sheep farms are only maintained at the cost of huge EU subsidies – but ones that Brexit will probably not end, as they are also supported by a British government in the pockets of the Farmers’ Union. Monbiot shows that the economic value of sheep-farming to rural communities is also much less than the revenue they could get from tourism if the uplands were rewilded – so the farmers are not even defending a coherent assessment of their own economic interests. One thing Monbiot does not discuss is also that hardly anyone in Britain even eats sheep any more – most of them are live-exported to Europe and the Middle East at the cost of huge animal suffering.

There are only a few pockets of land where re-wilding of the uplands has been tried – but sufficient to prove that it could be done. Monbiot finds those places in both Wales and Scotland (where, in the Highlands, it is deer rather than sheep that are the wreckers). Although much soil has been lost in some places, there is still sufficient in most of the uplands to support trees, together with vastly greater diversity and a much greater capacity for carbon absorption. The development and maintenance of rewilded land can be greatly aided by the re-introduction of top predators, such as wolves and lynx, who keep the numbers of grazing animals in check far more cheaply and effectively than humans can, preventing grazers destroying the forest, and in the process have a dramatic effect on the landscape.

Monbiot gives a big perspective on the possibilities for re-introduction. Reminding us that not that long ago, hippopotamuses were wallowing in what is now Trafalgar Square in London. He doesn’t realistically expect elephants and lions to be re-introduced into Britain any time soon, but does point out that the native vegetation is adapted to their presence: with the splitting properties of willows probably attributable to an ability to recover after elephant attacks. The environmental system has a complexity that we need to understand over a long period of time rather than only in the terms of one time and place. But the most striking aspect of his discussion of re-introductions to me is just the recognition that in some ways we need dangerous and inconvenient animals around for our own psychic health. If there is no wildness and threat, we tend to create our own substitutes, and these may actually be far more dangerous. Personally, reared in safe Britain, I’m not at all ready for coping with dangerous wild animals, and my experience goes no further than believing that a moss-covered trunk in Lapland was a bear, but I can see that it might be good for me to have to engage more fully with that unacknowledged area of experience.

Monbiot also talks at length about the sea, and the massive destruction of its life and biodiversity by nets that trawl the sea-bed. He narrates at length his personal experiences of dangerous forays off the Welsh coast in a kayak. I don’t share his enthusiasm for angling or his willingness to risk his life alone in small boats, but, again, I can recognise the value of this personal attempt to confront and engage with wildness, and the close connection it has with our embodied experience. In the end his argument about the sea is the same as that about the land: to rewild we have to preserve in a way that allows the biodiversity of the sea to redevelop to its amazing pre-industrial levels (where the tales of abundance are practically unbelievable today). Just as sheepwrecked pasture is not a ‘wild’ nature reserve by any stretch of the imagination, nor is a ‘marine reserve’ that still allows commercial fishing.

So what does this have to do with the Middle Way? It is obvious that absolutisation is closely related to the overexploitation and monoculture that has impoverished the environment, not just in Britain but across the world. Though there is also a reverse absolutisation that might try to deny the worth of human beings, the Middle Way nevertheless actually seems to demand quite a radical view – one that focuses on the long-term interests of human beings, rather accepting the deluded and short-sighted assumptions that support absolute monocultural answers of any kind. What is regarded as ‘moderate’ conventionally or politically is not likely to be anywhere near adequate in addressing the conditions here. The Middle Way instead takes us in the direction of allowing complex systems to form relatively stable structures that we are recognised to be a part of: i.e. getting rid of the bloody sheep.

Picture: ewe by George Gastin (creative commons – Wikimedia Commons)