Since early childhood, I have been fascinated by maps. I used to pore over my father’s old atlases from the 1930’s (where half the world was still pink), and then draw my own fantasy maps – which, as I became a teenager, turned into map-based strategy games drawn on grids of hexagons. Maps were a way of conceptually controlling a world of uncertainty, of creating and defending clear boundaries. In that way, despite their graphical nature, maps can be just another way of absolutizing, and the Middle Way can be a challenge to the assumptions we often make about them. What would a Middle Way geography look like?

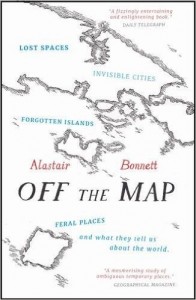

I have been stimulated to think more about this recently by reading a fascinating book called Off the Map by Alastair Bonnett. Off the Map is an account of a set of places that defy our assumptions about geographical boundaries. There are islands of silt, pumice, ice or rubbish that come and go. There are cities that change identity (such as Leningrad), or are totally deserted by humans (such as Pripyat near Chernobyl). There are no-man’s-lands such as Bir Tawil between the Egyptian and Sudanese borders, or an inaccessible traffic island in Newcastle. There is an enclave within an enclave within an enclave in the ‘Chitmahals’ of an incredibly complex borderland between India and Bangladesh. There’s the monastic republic of Mount Athos in Greece, where no women are allowed. Then there’s the self-declared independent country called Sealand based on an abandoned Second World War gun platform off the coast of Essex, England.

It is tempting to be Romantic about such places, to identify with them as brave redoubts against the bureaucratising imposition of normal geographical expectations. Sealand, for example, was created by a man called Roy Bates, who created himself Prince of his offshore gun platform and refused to pay British taxes. But this example is also clearly one of unsustainable fantasy. Bates’ obsessions were those of negative metaphysics such as the love of freedom for its own sake, merely counter-dependent on the positive metaphysics of the despised normal state and its boundaries. Sealand can be an apt illustration of the perils of relativism. If you absolutise your own independence you cut yourself lose from the values you relied on up till then. If you just deny your connection with your roots and their founding values and institutions rather than engaging in a critical relationship with them, you can end up in an unsustainable and vulnerable position. Sealand was first invaded at gunpoint, and then later exploited by others selling its passports from abroad at a massive profit.

If you absolutise your own independence you cut yourself lose from the values you relied on up till then. If you just deny your connection with your roots and their founding values and institutions rather than engaging in a critical relationship with them, you can end up in an unsustainable and vulnerable position. Sealand was first invaded at gunpoint, and then later exploited by others selling its passports from abroad at a massive profit.

Nevertheless, it is good to acknowledge many of the denied and forgotten places that Bonnett tells us about, whether they are empty cities in Inner Mongolia, remote Utopian communities in Russia, ‘dogging’ venues by an English lay-by, or children’s dens. The boundaries here are more about what we expect a community to be: populated, conventional, free of ‘private’ sexual activity, and known by adults. I think that provides one set of pointers towards a Middle Way geography. First we need to acknowledge that our ideas about places and boundaries are incomplete, riddled with holes and exceptions, and thus not absolute. But then we also need to acknowledge their provisional value in many cases. By looking a bit more closely, beyond the expectations either of an absolute boundary or of its denial, we find the messy uncertainties of experience once again.

What would that mean in practice for someone living in a more conventional city, town or village? Well, taking our political borders provisionally has implications for how we treat immigration, as I have argued in another blog post about the European refugee crisis. But beyond the political issues, Middle Way geography can also be linked to our attitudes to our own locality. If we treat it ‘mindfully’ (in Ellen Langer’s terms) by being open to new distinctions in that locality rather than relating to it in terms of fixed categories, even familiar localities will always reveal new features. Here’s a little exercise you can try now: look up at whatever room or other environment you’re in, and just note one new feature about it that you haven’t noted before. There, you are already engaging in Middle Way geography, by challenging whatever positive or negative fixed beliefs you had about that place.

Geography can hardly be neglected in the practice of the Middle Way, because it is a key aspect of human experience. Whether you like geography or not, you have a geography. Just by being an embodied being, you inhabit a place, and you interact with that place on the basis of beliefs about it. That place is then spatially related to lots of other places, to which you also relate in varying degrees. Your thinking about all of these places can be absolutised, or it can be made increasingly adequate to conditions by avoiding such absolutisation. This may just offer an alternative approach to aspects of your beliefs that you would otherwise engage with from different directions, but it is nevertheless a rich one.

Picture of Sealand by Ryan Lackey CCA2.0

Here’s a video I’ve just come across about the Indian/Bangladeshi ‘chitmahals’. Signs of hope that a Middle way has been found there, at least. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-aIzkvPwFo