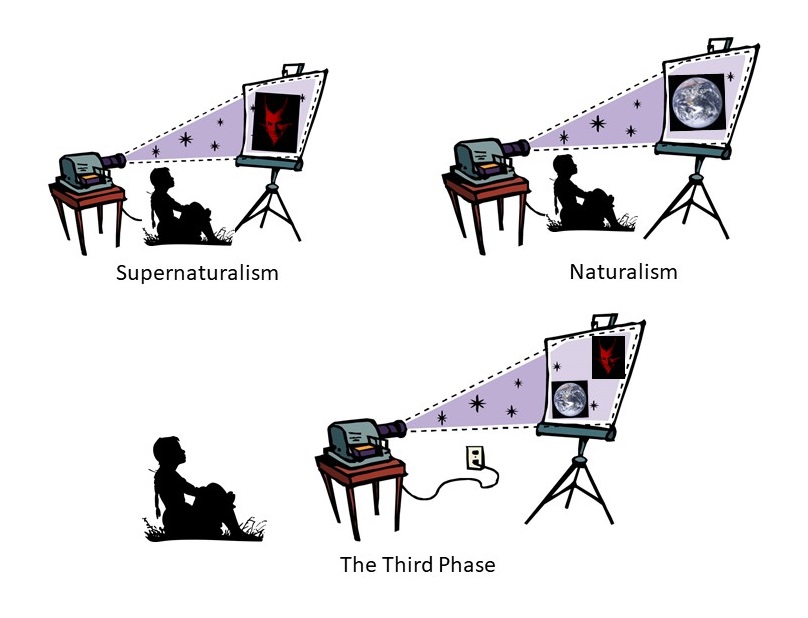

Back in 2013, I wrote a post on this site called the Third Phase. This suggests that, although nothing in history is inevitable, there do seem to be some signs that our civilization as a whole may be entering a new phase of engagement with conditions. You could see that as a new kind of science, philosophy, psychology, or practice. Here is the crucial part of that post that explains the three phases:

In the medieval era, complexity was ignored because of the over-simplifications of the ‘enchanted world’ and its unresolved archetypes. We mistook projections of our psychological functions for ‘real’ supernatural beings. A supernatural world provided a causal explanation for the world around us that prevented us from needing to engage with its complexity. The medieval era was gradually succeeded by the era of mechanistic science, in which linear causal mechanisms took the place of supernatural ones. Although we began to get to grips with the processes in ourselves and the universe, this was at the price of over-estimating our understanding of them, because we were using a naturalistic framework according to which, in principle, all events could be fully explained.

We are now gradually moving beyond this into a third phase of intellectual development. In this third phase, we not only develop models to represent the universe, but we also recognise and adapt to the limitations of these models. We take into account not only what we know, but what we don’t know. The signs of this third phase have been appearing in many different areas of intellectual endeavor.

Look at the original post for a list of what those areas are. They include complexity theory, embodied meaning, brain lateralization, and cognitive bias theory. These are all relatively new developments, involving psychology and neuroscience, that come together to offer the basis of a new perspective. But that perspective is not entirely dependent on them, and is actually far older, since it is another way of talking about the Middle Way. The Third Phase may arguably have first been stimulated by people living as long ago as the Buddha and Pyrrho.

What strikes me, looking back at this idea more than three years after the original blog, is how simple and obvious it is. The idea of being aware of our limitations is not at all a new one. It’s just the product of the slightly bigger perspective that I’ve tried to illustrate in the diagram above. You can merely be absorbed in the ‘reality’ you think you’ve found, probably reinforced by a group who keep telling you that’s what’s real, or you can start to recognise the way that this ‘reality’ is dependent on (though not necessarily wholly created by) your own projective processes. You look at that hated politician and see the Shadow. You look at scientific theories based on evidence about the earth and see ‘facts’. Or you can look at yourself seeing either of them, and also recognise that those beliefs are subject to your limitations. In both cases that doesn’t necessarily undermine the meaning and justification of what makes the politician hated or the theories highly credible. It just means that you no longer assume that that’s the whole story.

The third phase is not simply a matter of the formalistic shrugging-off of our limitations. It’s not enough just to say “Of course we’re human” if the next moment we go back to business as usual. The third phase involves actually changing our approach to things so as to maintain that awareness of limitation in all the judgements we make. I think that means reviewing our whole idea of justification. In the third phase, we are only justified in our claims if those claims have taken our limitations into account. That’s the same whether those claims are scientific, moral, political or religious. So it’s really not enough just to claim that such-and-such is true (or false) just because of the evidence. People have a great many highly partial ways of interpreting ‘evidence’, and confirmation bias is perhaps the most basic of the limitations we have to live with.

So far people have only really dealt with this problem in formal scientific ways, but science is like religion in being largely a group-based pursuit in which certain socially-prescribed goals and assumptions tend to take precedence, even if very sophisticated methods are used in pursuit of those goals. Such scientific procedures as peer review and double-blind testing are not the only ways to address confirmation bias, and they are applicable only to a narrow selection of our beliefs. The third phase, if it is happening, is happening in science, but it is also very much about letting go of the naturalistic interpretation of science: the idea that science tells us about ‘facts’ that are merely positively justified as such by ‘evidence’. In the third phase, science doesn’t discover ‘facts’, but it does offer justifications for some beliefs rather than others, and these are acknowledged as having considerable power and credibility. In the third phase, that is enough; we don’t demand an impossible ‘proof’. Better justified beliefs are enough to support effective and timely action (for example, in response to climate change).

The third phase involves a shift in the most widely assumed philosophy of science, but it is not confined to science. It is also a shift in attitude to values and archetypes. Some of us are still caught up in the first, supernaturalist, phase as far as these are concerned, and others in the second or naturalistic phase. Ethics and religious archetypes are either assumed to be ‘real’ or ‘unreal’, absolute or relative, rather than judged in terms of their justification and the limitations of our understanding. I do have values, that can be justified in my context according to my experience of what should be valued. At the same time, the improvement of those values also involves recognizing that they are dependent on a limited perspective that can be improved upon, just as my factual beliefs can be.

Perhaps what I didn’t stress sufficiently in my first post on the topic is that the third phase is not a matter of clearly-defined scientific breakthroughs. It is individuals who can start to exercise the awareness offered by the third phase with varying degrees of consistency. As Thomas Kuhn wrote of scientific breakthroughs or paradigm shifts, they actually depend on a gradual process of individuals losing confidence in an old paradigm and shifting to a new one. But there can also be a tipping point. When it starts to become expected for individuals to recognise the limitations of their justification, as part of that justification itself, social pressure can begin to be recruited to help prompt individual reflection.

We can hope for some future time when the third phase is fully embedded. When religious absolutists stop assuming that the way to make children more moral is to drill them in dogmas. When secularists get out of the habit of dismissing whole areas of human experience in their haste to find a secular counterpart to religious ‘truth’. When promoting understanding of the workings of our brains is no longer considered suspiciously reductive. When the public is so well educated in biases and fallacies that they complain to journalists who let politicians get away with them. When evolutionists respond to creationists not by appealing to superior ‘facts’, but solely by pointing out deficiencies in the justification of creationist belief, in ways that apply just as much in the realm of ‘religion’ as in that of ‘science’. Yes, we are still a long way off the entrenchment of the third phase. We can only try to get it a little more under way in our lifetimes.

Please don’t write “science is like religion”… this is usually a phrase taken right out of The Obscurantist’s Handbook. (Yes, sorry, I know this is insulting your great work, but I’ve been into “climate debate” for a decade too long…) Yes, scientifical tools are “are applicable only to a narrow selection of our beliefs”. But this narrow selection can (and in the 3rd phase must) be crucial building blocks of our judgement. Paradigm: We are now an integral part of the global carbon cycle, Earth is no longer flat for all practical purpose (as it was until late last century), and if can’t admit that (first) and then try to live up to that practical as well as moral challenge, then we can forget about anything Homo Sapiens.

Science is not a raft as in the Buddha’s parable, to be left behind when the river is crossed. It more like the glasses that keep riding the nose even while the bespectacled enters nirvana…

Hi Martin,

I think the respect in which I was comparing science with religion is clear enough, so any passing resemblance to obscurantism will be just that, a passing resemblance, not a significant one (as you seem to recognise). If you’re implying that I could be misunderstood – well, yes I could – but in both directions.

I do thoroughly accept the practical value of science, and part of my case is that the arguments for recognizing global warming are more likely to be effective if they make it clear that the judgement is a pressing practical one rather than one of ultimate ‘facts’. I’m not sure about the glasses metaphor (which suggests a more basic framing than that of formal scientific activity), but I’m prepared to accept that the river we are crossing on the raft is a very wide one indeed.

I’ve today read this piece by David Chapman, and it seems to more or less parallel what you’ve said in this article but using his terminology and – importantly for me – with a STEM slant:

https://meaningness.com/metablog/bongard-meta-rationality

If I remember correctly, he talks about the practice of science requiring meta-rational skills (which imply a higher level of integration), as it isn’t just about blindly applying rules (which can easily be absolutised by those operating in a rational/systematic mode) but about trying out different rules, understanding that there always must be fuzziness or ambiguity at some level.

Chapman weaves Kegans adult developmental stages into his ideas, which might be useful for considering the Middle Way and how it might help, and who might adopt it. The ideas in Middle Way philosophy are Meta-rational, and so will only be accessible to people within Kegans fifth order – this might signify an obstacle to promoting the middle way, since few people seem be be at fifth order, and those at fourth will misunderstand it and possibly resist it (for reasons made clearer in Chapmans articles) and those at third order will just plain misunderstand it, maybe using their misconstrued version to strengthen their own 3rd order (irrational, as defined by Chapman) ways. On the other hand it may also provide another way of looking at the importance of something like the Middle Way Society, as it exists to promote the Middle Way, and as such may help people at 4th order to make the difficult transition to Kegans 5th order. The article I linked above is describing a way of helping shift STEM oriented people (such as myself, and many of the people I know) away from systematic, rational (eternalistic, scientistic) worldviews towards a more integrated meta-rational worldview.

For more see Chapman’s most recent article, which (amongst other things) considers why meta-rational thinkers may have shot themselves in the foot to some extent by repelling rational thinkers and entrenching irrational thinkers: https://meaningness.com/metablog/rationalism-critiques

Hi Jim,

Thanks for bringing my attention to this: it’s very interesting indeed. I’ve had a fair amount of contact with David Chapman a few years ago, but have ceased to keep up with him – and I’ve obviously been missing some good stuff.

One thing I’d want to stress in relating Chapman’s thought here to the Middle Way is that the Middle Way (being a way) leads from wherever we are forward. So for someone in Kegan’s stage 3 it might be the way to stage 4. But, yes, I also agree that if what you’re focusing on is the distinctive perspective offered by the Middle Way, it does depend on stage 5 type development to be understood.

Kegan’s moral development hierarchy is also interesting from the point of view of brain lateralisation. You could see it as an alternating process of strong left hemisphere control (stages 2 and 4), punctuated by the relaxation of that control to enable new conditions to be addressed (stages 3 and 5). I’m thus not entirely convinced that one has to pass through all these stages quite as neatly as the model suggests. There does need to be absolutized ego to integrate, but the integration of the conflicts created by stage 2 might be sufficient for that. Or perhaps stage 2 can adopt some of the features of stage 4 and stage 3 can adopt some of the features of stage 5. The model probably needs quite a lot of critical examination before it can be trusted to take too much weight, I think.

So, it does look as though there’s a rich seam of material to be mined here that may illuminate the Middle Way. I can see how the Bongard tests might be useful, for instance. But I would be cautious about identifying the Middle Way too hastily entirely in the terms of Chapman’s terminology.