Spoiler Alert: This isn’t a synopsis or a review but I will reveal certain, important, plot points. As such, if you haven’t yet seen it yet – and would like to – you may want to stop reading now.

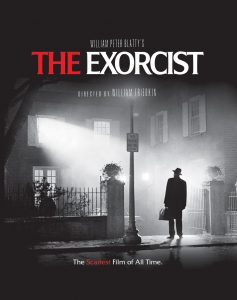

Cursed. Obscene. Scary. Nauseating. Pea Soup. These are just a selection of words  associated with William Friedkin’s 1973 film, The Exorcist (adapted from William Peter Blatty’s novel of the same name). The Exorcist tells the story of the Exorcism of 12-year-old girl, Regan MacNeil, who has been possessed by a malevolent force. It is set in affluent 1970’s Georgetown USA, where Regan lives with her atheist mother, who also happens to be a famous actress.

associated with William Friedkin’s 1973 film, The Exorcist (adapted from William Peter Blatty’s novel of the same name). The Exorcist tells the story of the Exorcism of 12-year-old girl, Regan MacNeil, who has been possessed by a malevolent force. It is set in affluent 1970’s Georgetown USA, where Regan lives with her atheist mother, who also happens to be a famous actress.

Even in the early 1990’s, when I was at school, this film had a reputation as being the most disgusting and frightening film ever made – which of course meant everybody wanted to see it. This desire was only intensified by the fact that The Exorcist had been banned in the UK since 1984; a few friends and I even attempted to watch a pirated copy of it on VHS, but  our excited anticipation was soon extinguished once we realised that the video quality was so bad as to render further viewing impossible. In 1998 the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) lifted the ban, and The Exorcist was released – with much fanfare – in cinemas across the country. Many of my peers came back with reports of disappointment and boredom. ‘It’s not scary at all. I didn’t jump once’ they’d say, or ‘I don’t know what the fuss is about, nothing even happens for most of the film’. I was worried. I’d recently read the book and really enjoyed it, but wasn’t sure how it would be translated into the ‘Scariest Film Ever Made’. Could this really be the same film that had caused people to faint and vomit while watching it? I knew loads of people who’d seen it the first-time round and refused to even talk about it, let alone watch it again. Perhaps it hadn’t aged well?

our excited anticipation was soon extinguished once we realised that the video quality was so bad as to render further viewing impossible. In 1998 the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) lifted the ban, and The Exorcist was released – with much fanfare – in cinemas across the country. Many of my peers came back with reports of disappointment and boredom. ‘It’s not scary at all. I didn’t jump once’ they’d say, or ‘I don’t know what the fuss is about, nothing even happens for most of the film’. I was worried. I’d recently read the book and really enjoyed it, but wasn’t sure how it would be translated into the ‘Scariest Film Ever Made’. Could this really be the same film that had caused people to faint and vomit while watching it? I knew loads of people who’d seen it the first-time round and refused to even talk about it, let alone watch it again. Perhaps it hadn’t aged well?

When I did eventually get to see it that I could understand why my peers were confused about the reputation it had achieved. I’m not the kind of person that finds Horror films particularly scary anyway, but I had expected The Exorcist to be an exception. It wasn’t. In this respect, the length of time that had passed since its original release did seem to have had an impact. Horror films throughout the 90’s had a tendency to reject the kind of subtle psychological techniques used in the 60’s and 70’s in favour of ‘jump scares’ and ‘gore effects’. Therefore, that is what any teenager going to see a Horror movie at this time would be expecting. That’s not what they got with The Exorcist. There’s hardly any ‘gore’ and it is almost entirely void of ‘jump scares’. In addition to this, much of imagery was much less shocking in the 90’s than I suspect it would have been to a 70’s audience. With these considerations in mind I can understand many of my peer’s sense of disappointment – in this respect it had not lived up to the hype. However, as much I wasn’t scared in the cinema, I loved it. I found it absorbing in a way that few films had been and was surprised by the skilful way in which it created an atmosphere. The deep layers of meaning hidden within the imagery and narrative demanded repeated viewing. It is a deeply unsettling film and I found that it stayed with me (as the book had) long after I’d left the cinema; something that did not happen with contemporary horror films such as ‘I Know What You Did Last Summer’ (which is instantly forgettable). While it wasn’t what the hype had lead me to believe it would be, The Exorcist, as a film, had aged very well indeed.

After a period of about 10 years, where I watched it quite a lot, I spent a further 10 years without seeing it at all. That is, until a few months ago, when I heard Mark Kermode (film critic and Exorcist expert/ super-fanboy) discussing it on the radio. With some trepidation  – I feared that it really might have aged badly by now – I sought out a copy and sat down to watch it again. I needn’t have worried, it stands up incredibly well & I enjoyed it just as much (if not more) than I had before. More importantly for this blog however, I also realised that it related, both stylistically and narratively, to the Middle Way.

– I feared that it really might have aged badly by now – I sought out a copy and sat down to watch it again. I needn’t have worried, it stands up incredibly well & I enjoyed it just as much (if not more) than I had before. More importantly for this blog however, I also realised that it related, both stylistically and narratively, to the Middle Way.

Watching The Exorcist is a physical experience. I know that watching any film can be described as a physical experience, we are embodied beings after all, but The Exorcist goes further. You can feel the cold of Regan’s bedroom. You can smell her necrotic breath as she lies, unconscious on the bed. I don’t understand what cinematic tricks are used to create this effect but I suspect that it has as much to do with the sound as it has with visuals. The ambient sound is hypnotic and the groaning rasp that accompanies Regan’s breathing creates a powerful and absorbing effect. There are other scenes where the combination of visuals and sound work together to create the experience of embodied physicality, such as when Regan is made to undergo a range of intimidating and painful medical tests.

On the surface, The Exorcist is a fairly standard tale of good versus evil; light overcoming darkness. During the first scene – where an elderly Jesuit priest, Father Merrin, is seen attending the archaeological excavation of an ancient Assyrian site in northern Iraq – the contrast between quiet contemplation and loud commotion is jarring. While the scene is set within the suffocating glare of the desert sun, it is also pierced with dark imagery. It’s within this context that we finally see an increasingly disturbed Merrin wearily, but defiantly, facing a statue of the Assyrian demon Pazuzu. It is no coincidence that this scene brings vividly to mind the Temptation on the Mount, where Jesus overcame Satan’s attempts to divert him from his holy path to righteousness. I’m sure that this premonition of the battle to come, is constructed and representative of several Jungian archetypes, but I’m not familiar enough to identify them all. However, I’m confident that there’s the Hero, the Shadow, God and the Devil; the latter two also being representations of two metaphysical extremes: absolute good and absolute evil. The key point however is that Father Merrin is not God (or even Jesus) and the statue is not the Devil (or even Pazuzu), they are both the imperfect embodiments each.

On the surface, The Exorcist is a fairly standard tale of good versus evil; light overcoming darkness. During the first scene – where an elderly Jesuit priest, Father Merrin, is seen attending the archaeological excavation of an ancient Assyrian site in northern Iraq – the contrast between quiet contemplation and loud commotion is jarring. While the scene is set within the suffocating glare of the desert sun, it is also pierced with dark imagery. It’s within this context that we finally see an increasingly disturbed Merrin wearily, but defiantly, facing a statue of the Assyrian demon Pazuzu. It is no coincidence that this scene brings vividly to mind the Temptation on the Mount, where Jesus overcame Satan’s attempts to divert him from his holy path to righteousness. I’m sure that this premonition of the battle to come, is constructed and representative of several Jungian archetypes, but I’m not familiar enough to identify them all. However, I’m confident that there’s the Hero, the Shadow, God and the Devil; the latter two also being representations of two metaphysical extremes: absolute good and absolute evil. The key point however is that Father Merrin is not God (or even Jesus) and the statue is not the Devil (or even Pazuzu), they are both the imperfect embodiments each.

Understandably perturbed by her daughters increasingly disturbing behaviour, Regan’s mother seeks the help of neurologists and then physiatrists. Both fail to identify a cause and both fail to succeed in their interventions. Eventually, the perplexed psychiatrists suggest that Regan’s exasperated mother enlist the services of a priest, to which she reluctantly agrees.

The priest that she finds is a man called Father Damian Karras. Karras is unlike Merrin, whose background is not really explored, in that he is clearly a conflicted and complex character. We see him caring for his elderly mother, when no one else seems willing to, and we also see him, dressed in his Jesuit regalia, turn away from a homeless man who asks for his help. Karras, then, is not a bad person, but neither is he that good. The viewer is left to wonder the nature of this priest’s faith. When we add to this the fact that he is a scientist (psychiatrist) as well as a priest, we start to see the depiction of a complex, multifaceted individual who struggles, in all aspects of his life, through the messy middle in which we all exist.

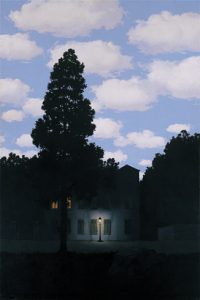

Karras, who is not qualified to perform the Exorcism ritual, convinces the Church of Regan’s need and Father Merrin is subsequently called upon. The moment when he arrives at the house and looks up at the room which contains the possessed girl is inspired by The Empire of Light, a series of pictures painted by René Magritte in 1953-4. As with the opening sequence, we are shown our archetypes juxtaposed in preparation for battle; this striking image was also used as the now famous promotional poster (which I used to have on my bedroom wall). The clichéd battle between good and evil begins. Except it doesn’t… not really. Like the statue of Pazuzu, Regan is not an absolute representation of evil; she has been embodied by evil but is not the embodiment of it – she’s a 12-year-old girl. Father Merrin is not the embodiment of good, he is just a representative of Christ (and therefore God). This is made explicitly clear (if it wasn’t already) in an extended scene where the two priests desperately shout, ‘the power of Christ compels you, the power of Christ compels you’ over and over while throwing Holy water on the levitating girl. A lesser film would have Merrin eventually defeat the demon and save the girl, but this is not what happens. The elderly Exorcist dies during the gruelling exchange and Karras is left facing the demon alone. Again, a lesser film would have Karras take up the role of Exorcist and overcome the evil force against all odds. This is not what happens. Religion, like science before it has failed and Karras appears to be in a hopeless predicament. In the heat of the moment he takes the only course of action that he feels is available to him; he grabs Regan and shouts

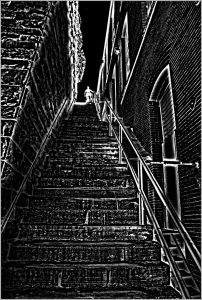

Karras, who is not qualified to perform the Exorcism ritual, convinces the Church of Regan’s need and Father Merrin is subsequently called upon. The moment when he arrives at the house and looks up at the room which contains the possessed girl is inspired by The Empire of Light, a series of pictures painted by René Magritte in 1953-4. As with the opening sequence, we are shown our archetypes juxtaposed in preparation for battle; this striking image was also used as the now famous promotional poster (which I used to have on my bedroom wall). The clichéd battle between good and evil begins. Except it doesn’t… not really. Like the statue of Pazuzu, Regan is not an absolute representation of evil; she has been embodied by evil but is not the embodiment of it – she’s a 12-year-old girl. Father Merrin is not the embodiment of good, he is just a representative of Christ (and therefore God). This is made explicitly clear (if it wasn’t already) in an extended scene where the two priests desperately shout, ‘the power of Christ compels you, the power of Christ compels you’ over and over while throwing Holy water on the levitating girl. A lesser film would have Merrin eventually defeat the demon and save the girl, but this is not what happens. The elderly Exorcist dies during the gruelling exchange and Karras is left facing the demon alone. Again, a lesser film would have Karras take up the role of Exorcist and overcome the evil force against all odds. This is not what happens. Religion, like science before it has failed and Karras appears to be in a hopeless predicament. In the heat of the moment he takes the only course of action that he feels is available to him; he grabs Regan and shouts  at the demon, ‘take me, take me’. The demon gladly obliges and, a now possessed, Karras – who already exists somewhere between good and evil – is able to throw himself out of Regan’s window, where upon hitting the ground he falls down a flight of steep stairs, where he dies, presumably taking the demon with him and leaving Regan to make a full recovery.

at the demon, ‘take me, take me’. The demon gladly obliges and, a now possessed, Karras – who already exists somewhere between good and evil – is able to throw himself out of Regan’s window, where upon hitting the ground he falls down a flight of steep stairs, where he dies, presumably taking the demon with him and leaving Regan to make a full recovery.

Science, religion and the explicitly archetypal forces of good have not triumphed over evil and, in this muddled mess, appeals to authority do not always provide the promised solutions. Instead our Middle Way hero, who’s able to hold onto his beliefs lightly, is left to address challenging conditions as they arise. The solution he finds, I would like to suggest, seems remarkably like an extreme example of the ‘two donkeys’ analogy that is a favourite of this society. By integrating competing desires, he is able to overcome conflict, albeit at great cost to himself.

I haven’t seen this film, but find this interpretation of the story very interesting. What worries me slightly about your interpretation of the end of the story is that it appears to be self-sacrificial. Isn’t self-sacrifice as likely to be an absolute as any other value – indeed more so because it often involves repressing instinctual self-regard? It sounds as though Father Karras may be being offered as a Christ-like figure, not just in the sense of mediating between absolutes and humanity, but in the sense of self-sacrifice. Not having seen the film, of course, I don’t know whether its presentation of the events emphasises that intention.

Then there’s the whole belief in demonic possession in the modern context – a belief that itself may be seen as absolutist when there are alternative psychological explanations available (which, of course, there weren’t in the Biblical context). By turning a mental illness into a ‘demon’, aren’t we often projecting outwards into a negative absolute something that is an incremental problem in the individual? I guess I would have much preferred an ending that emphasises the humanity of the girl, as well as that of the priest, and recognises in some way that the problem has been unnecessarily absolutised, without undermining the powerful meaning of the archetypes being depicted.

Hi Robert,

It’s interesting to me that you mention the ending, because this is the part of my argument that I have less confidence in, but before I go further with that I think it might be helpful to briefly explore how Blatty (the author and screen writer) saw the film.

As I understand it Blatty, a Catholic, said that he saw the film very much in terms of good overcoming evil; God overcoming Satan. It has even been said that The Exorcist was a very effective piece of Catholic propaganda, which had a measurable effect on the numbers of practising Catholics. What interested me, however, was that the film is much more ambiguous than this, to such an extent that the long gruelling battle between the two forces really ends with the ‘evil’ party being victorious. Almost all of what the priests did before Karras throws himself out of the bedroom window could be argued to have been futile.

My point here is that, like the story of Adam & Eve, there is one, literal, way to understand it. However, there are deeper layers of meaning in which the Middle Way can be found – even if this is not what the author intended. With Genesis there is no way of knowing the authors intentions, but the way that the Exorcist ends causes me to suspect that Blatty was well aware that his story could, and should, be interpreted in more nuanced ways than good vs. evil.

With regards to self-sacrifice, I don’t think that such action is always an absolute contradiction of the Middle Way. There must be times when people have to make quick decisions in dangerous situations in which they conclude that the right course of action is to put oneself in harms way for the benefit of another, and I would argue that such a decision could be the result of Middle Way thinking. Karras made such a decision. If he had more time then perhaps he could have constructed a better solution, but circumstances do not allow for this. Moreover, the film would be much less dramatic if Karras, Regan and what ever it is that is possessing her come to a reasonable compromise. I hadn’t thought of Karras’ sacrifice as Christ like, but I suspect that the correlation is deliberate. Having said that I would not say that Karras is Christ like character, rather he is made up of many archetypes, the Christ being one of them.

The issues you raise about possession and mental illness are urgently valid, especially as there are still many communities in which those with mental illness are declared as being possessed, and treated appallingly. However, The Exorcist does attempt to deal with this. As a famous and wealthy actor, Regan’s mother is able to afford the best Neurological and Psychological treatment available, all of which fails. It makes it clear that what ever is happening to Regan, it is beyond contemporary understanding. The Church is only approached as an act of desperation, and the Church itself is reluctant to get involved.

The other point relevant to the possession is that it is never really made clear what or who is causing it. There are allusions to Pazuzu. The ‘demon’ identifies itself as the Devil and also claims that there are many personalities residing within Regan, including Karras’ mother. Merrin contests this by saying that there is only one and that the demon is playing tricks, but we have his word on this point. Like other aspects of this film the nature of Regans possesion is ambiguous, even if is clear that her life is in immediate danger.

I think that Regan’s humanity is at the heart of the film, and it is this that makes it so effective. The viewer never loses site that at the centre of this situation is a young girl. In this sense the Priests are merely trying to save a child rather that defeat evil for it’s own sake.

I could have been more critical, but really I wanted to demonstrate why I like the film so much and demonstrate the deep layers of meaning contained within it, much of which can be viewed through the prism of the Middle Way.

To develop a Middle Way interpretation of a film like The Exorcist felt ambitious, but some of the points I made in the blog seemed so striking that it seemed worth while. I do hope that people who haven’t seen it give it a go (or read the book instead), but I understand that it will not be to everyone’s taste. For my part The Exorcist seems to reveal something new to me each time I watch, which is impressive considering how many times I have seen it. I like the fact that it means something different to me now, than it did when I was 17.

Thanks Rich. I agree that a self-sacrificing action could potentially just be the most adequate response to a particular situation – it’s just that we have a long history of Christian absolutisation of self-sacrifice to deal with here!

As regards the overall intention, whether it has other layers of meaning, and the treatment of mental illness, I should obviously watch the film before venturing any further comments!

Like you, Rich, I went to see this film in the cinema when the ban was lifted, after hearing Mark Kermode wax lyrical about it (on Radio 1 in the evenings). I haven’t watched it since though, but the main things I remember were the oppressive painful medical tests that the girl was put through (screaming at points) and the dramatic ending with its self-sacrificial element.

Robert – in the film there doesn’t seem to be any other way of interpreting what is going on other than a ‘demonic possession’, firmly in the land of fantasy and the supernatural – unless the levitation and such was very explicit hallucination (or some other kind of special pleading is used). It is what always feels a bit weak to me about supernatural fantasy – how do the ordinary human beings with their mortal bodies have any way of winning a battle with supernatural entities? I don’t even think it can be used to represent the way that we have to find ways of coping in the face of seemingly insurmountable problems, or things that we have very incomplete knowledge of.

Just to add – in 2001 I watched “2001: a space odyssey” in the cinema, for the first time. I found that a more effective horror, in the form of HAL, in the ‘what monster have we created?’ kind of way. That too went a bit off the rails at the end though, in a film that in every other way had taken great lengths to accurately portray realism about the physics and conditions of space flight.

Hi Jim,

Yes, 2001 is a great film (I don’t understand the ending at all) and Sci-fi is often more horrifying than supernatural horror. As someone who remains sceptical about supernatural experiences, sci-fi seems to explore situations that seem more within the realms of possibility. The recent television adaptation of The Handmaids Tale is a great example of this.

Having said that I can still find supernatural films to be effective. There are many reasons for this, I suspect. Firstly, although I do not find it helpful to give supernatural explanations for events – just because there no other possibility is immediately evident – I do think that people experience unexplainable, weird and frightening things. I don’t think that because I don’t believe I’m immune to such experiences, and I suspect I would be a frightened as anybody else. Secondly, if the film makers do a good job then they can create a scenario that I can ‘believe’ in, however improbable. Finally, and relating to the previous two points, I am open to the possibility that things that I find improbable could happen. I might be wrong, perhaps ‘possession’ might be a possibility. How would I react if it became apparent that it is and it was one of my lived ones affected?

The ‘medical test’ scenes have only stood out to me upon recent viewing, and I did find them very affecting. It seemed to elicit an empathy response that caused me to ‘feel’ like I was there with Regan, experiencing what she was (even though I clearly wasn’t). These scenes can be interpreted in several way, I think, and one might conclude that they are anti-medicine, anti-scientific. I don’t see it that way though.

There is a desperation to it, a desperation to find a cause and to then be able to relieve the suffering. I think that it also serves to demonstrate that medical interventions can (and often are) frightening, invasive and painful. Therefore when we later see Regan strapped to her bed (in order to prevent harm to herself and others) with two priests shouting at her, as they throw holy water, we can recognise the similarities. Both experiences are unpleasant and both are being carried out in good faith, as attempts to relieve suffering.

Although I don’t think this was the purpose of the scenes, they also raise questions about how we view those who treat those deemed possessed with brutality. To what extent do they believe what they are doing are acts of kindness? When we see such treatment our instinct is to assume that the people doing it are being intentionally cruel, evil and sadistic, but if such behaviour and beliefs are to be challenged effectively don’t we need to try and understand the motives of those who carry them out? Motives that may not always seem as they first appear.

This book by Mark Kermode looks like a detailed analysis. I’ll have to get a copy.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Exorcist-BFI-Modern-Classics/dp/0851709672

There is about a page on Jesus’ exorcism of ‘Legion’ in my forthcoming book ‘The Christian Middle Way’ – which I’ll extract here in case it’s of interest.

The exorcisms also provide an impression of Jesus as integrated and thus as able to help others achieve integration when they are subject to the horrific internal conflict we now tend to call mental illness. Perhaps the most striking example of this is the exorcism of ‘Legion’.

“Jesus asked him, ‘What is your name?’ ‘Legion,’ he replied. This was because so many demons had taken possession of him. And they begged him not to banish them to the abyss. There was a large herd of pigs nearby, feeding on the hillside; and the demons begged him to let them go into these pigs. He gave them leave; the demons came out of the man and went into the pigs, and the herd rushed over the edge into the lake and were drowned. “(Lk 8:26-33)

The multiplicity of conflicting identities may be associated with what we might now call schizophrenia or multiple personality disorder, and the personification of these identities as ‘demons’ is not irrelevant to modern understanding. As discussed above, the archetype of the Shadow can be associated with Satan, as it can with other devils or demons: beings that are constituted by the narrow hatred of our rejection of them. The less integrated we are the more demonic our experience becomes, as it becomes more dominated by qualities like power, obsession, craving, defensiveness, impatience, literalness and despair, and these qualities either take us over or are temporarily rejected and then reassert themselves. Iain McGilchrist also discusses the links between over-dominant left-hemisphere states and schizophrenia.

The ending of the demonic possession is presented as an exorcism – i.e. a conflict between Jesus using divine power and the demons as separate, negative supernatural entities. However, there are many hints in the narrative that can help us interpret it in a way that simply reveals Jesus’ integration and the overwhelming effect that could have on others. One such hint is the way that the demons immediately recognise Jesus and are overawed. They recognise that here there is a perspective far beyond their conflicted world, but, given their limitations, fear is the dominant response. Integration, to a demon, looks like conflict in which absolute force is used against them. So the demon cries, on first seeing Jesus “What do you want with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? … I implore you, do not torment me” (Lk 8:28). Another indication is the way in which Jesus does not simply destroy the demons or ‘banish them to the abyss’. Instead, they are allowed to go into the pigs. Whatever we may think of this from the animal welfare point of view, Jesus is here using his influence to challenge absolutised conflict, and avoiding a merely negative absolutism in response by providing an alternative for the demons. The demons then destroy themselves rather than being destroyed by Jesus. In the same way, whatever our demons may be, we cannot merely destroy them or banish them. The Middle Way suggests that we should be deliberate about not adopting their narrow assumptions, but that we should provide their energies with alternative directions in which to flow.

Hi Robert,

Blatty’s follow up novel, to the Exorcist, is called ‘Legion’, and as with Karras’ ‘christ-like’ sacrifice, this story – as you have interpreted it here – can also be applied to the final moments of the film. As well as representing Christ he also plays the role of the pigs. I could not argue that Karas is a well integrated individual, but he does seem open to experience. He is also not fixed to dogmatic beliefs, nor does he submit – unquestionably – to any authority, despite being a Jeusit priest. The dialogue below is the point in the film where Karas meets Regan, who claims to be, first the Devil, and then multiple ‘personalities’:

Karras: Hello, Regan. I’m a friend of your mother’s. I’d like to help you.

Regan: [possessed voice] You might loosen these straps then.

Karras: I’m afraid you might hurt yourself, Regan.

Regan: I’m not Regan.

Karras: I see. Well then, let’s introduce ourselves. I’m Damien Karras.

Regan: And I’m the devil. Now kindly undo these straps!

Karras: If you’re the devil, why not make the straps disappear?

Regan: That’s much too vulgar a display of power, Karras.

Karras: Where’s Regan?

Regan: In here. With us.

I’ve found this 2010 video clip of Mark Kermode explaining his love of the Exorcist.

https://youtu.be/xcUXtEeVy-Y

I thought I’d share my excitement that this blog has now been read and endorsed by William Friedkin himself.

Excellent!

This is a legend of a movie in its own right. A subtle shriek of despair is sensed throughout the movie that makes for the background score . An atmosphere builts up. It is stifling and frightening would not be the right word, let’s say it is disturbing and the phycological assault straight affects your system, the cardiovascular system to be precise. Pea soup vomit, flash of demon face on wall for split second or the unknown shadow at Regan’s shuttered window pain all converge into a heightened sense of cold creeps. It stays in your system at the back of your neck long after you have seen the movie.