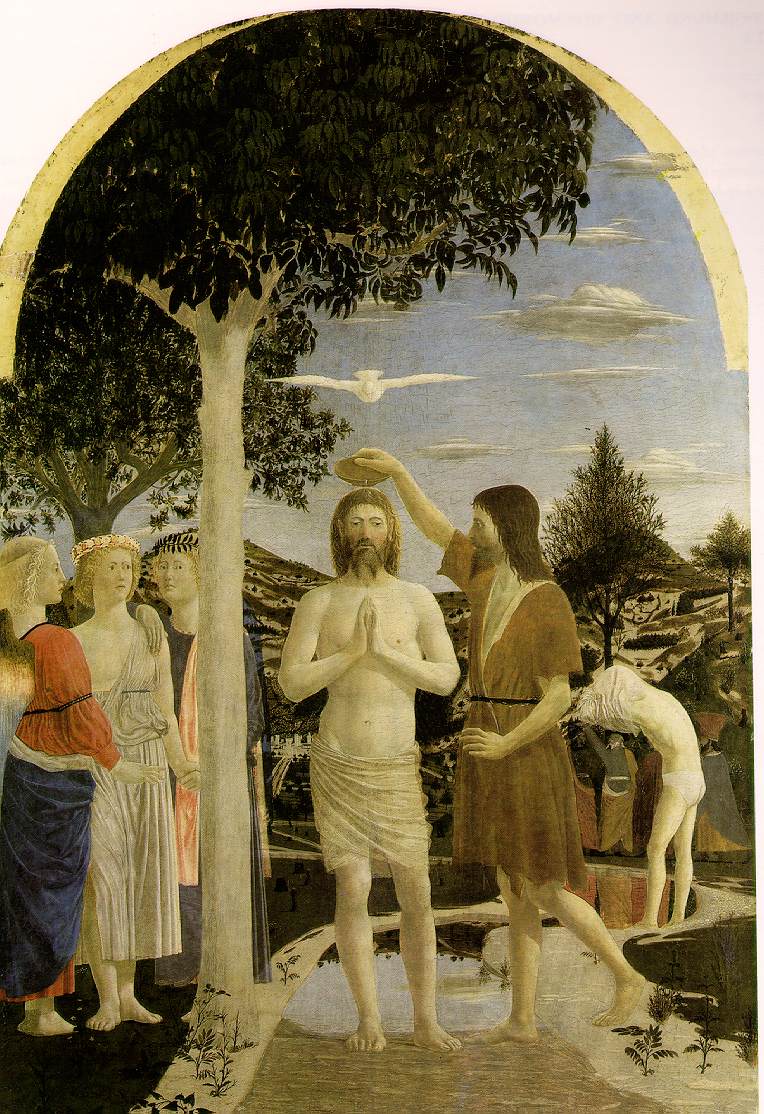

This is one of the best-known paintings of the Italian Renaissance, a classic depiction of a Biblical scene: that of John the Baptist baptising Jesus in the Jordan. Like many such paintings, there is also much more to it than may initially meet the eye. I have been thinking a good deal recently about the life and teachings of Jesus, and the ways that we could choose to interpret them in terms of the Middle Way. You could ‘read’ this painting only in terms of dogma and discontinuity if you wished: as a symbol of purity (a concept that it often absolute), and of Jesus’ claimed power as the Son of God. But it is much richer and more ambiguous than that. I choose now to understand it more positively.

One of the first things that has puzzled me about this painting is that, although the gospels clearly say that Jesus was baptised in the river Jordan, here there is no sign of the river. The reason for this may be that Piero was following a medieval story that the Jordan miraculously stopped flowing at the time of the baptism – so that we are meant to be looking at a dried up river bed. But this may have quite different resonances today, focusing not on miracle stories but on the meaning of an exposed river bed. The drying up of a great river is an ecological catastrophe, but to engage in a quiet, reflective ceremony in those circumstances has a special power. In the face of dramatically adverse changes in conditions such as droughts, wars and revolutions we more than ever need to find a point of reflectiveness and openness in order to adapt.

The sacredness of the ceremony is emphasised by Piero’s unique use of pallid colours, by the balance of the picture around the figure of Christ, and by the spectators. According to the gospel narratives, Jesus had just returned from his temptation in the wilderness: a story that bears some very interesting parallels to the story of the Buddha going out into the jungle. He is now about to return to society and share the insights that he has found in solitude, but to do this successfully he will need awareness, confidence, resolve and support from others. Interpreted positively and experientially rather than just as a conversion ceremony, baptism is a rite of passage that could help a person to integrate all of these things.

The figure of the dove above Jesus, representing the Holy Spirit, more than anything reminds us of the God archetype as Jesus might have been experiencing it at that moment: as a glimpse of his own potential as a fully integrated figure. To maintain a strong link with that potential we need a stable awareness of a right hemisphere perspective to supplement the narrow and goal-driven left-hemisphere dominant state, and the solemnity of a ritual can help achieve this.

But, apart from Jesus and John the Baptist, there is another very important presence in the painting: the tree immediately to the left of Jesus. Experts say this probably depicts a walnut tree such as Piero would have been familiar with in Italy. It is this tree that for me, more than anything else in this picture, that helps put Jesus’ baptism in a genuinely spiritual setting based on the Middle Way. The tree can represent the process of integration as one of organic growth, taking up nourishment through its roots from shadowy and rejected energies in ourselves and transforming them incrementally into a finished, balanced organism. I have already written in an earlier blog about the Tree of Life motif as it is used by Jung in his Red Book, and the Tree of Life can be a powerful alternative symbol for the Middle Way.

On the left hand side are three spectators that I at first did not realise are intended to be angels. One of them has a pink garment that may be intended to re-clothe Jesus after the baptism. An interesting tradition also links these three figures to a process of reconciliation in the Church (and thus to a Middle Way between opposed beliefs). Nicholas Cranfield explains:

A once popular recension of scholars convincingly argued that the picture alludes to the then recent Council of Florence that in 1439 had briefly, and importantly, forged a concordat between the Western and the Eastern Church, a short-lived salve for the centuries’ old rift that had breached Christendom since 1054 and which re-opened soon after the collapse of Constantinople in 1453. Such a ‘reading’ hinges on the gesture of the two angels closest to the Lord, watched by the third, the (?)Archangel, a seemingly superior angelic being. The angels immediately to the right of Jesus take hands in a classical gesture that is associated with Concordia and the Augustan tradition of peace. (from a sermon given in 2004)

The undressing figure depicted behind John the Baptist is also quite striking. His presence seems to emphasise that Jesus’ baptism was not unique: that there were many other people going through the same process. Jesus was not the first or the last to be baptised, or to go through a process of integration. The water and sand behind the main figures also resembles a winding (flooded) path, so we could also see the undressing man as representing another point in the path behind Jesus. We could even interpret him as Jesus himself at an earlier point in time, following the cartoon-like conventions often found in early Renaissance paintings whereby the same figure is represented at different points in a story within the same picture.

In the end, though, I find that such interpretations can only contribute to an overall impression in which aesthetic appreciation of light and colour, awareness of symbol, and a sense of cultural context merge with a recognition of Piero della Francesca’s overall moral and spiritual purpose. My understanding of Jesus as a figure and of the archetypes he invokes are both affected by this picture and feed back into my understanding of it. It seems to be not for nothing that this is such an acclaimed picture in the history of art.

The picture can be seen in the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery, London.

Links to earlier art blogs by Robert M Ellis:

The Tower of Babel by Breughel

Given the original was in a church you might be interested in this for the middle way –

The original setting was between two paintings of Peter’s Keys and Paul’s witness as he was put to the sword. The pale colours and blue would have blended with the blue in the background of those panels. Was there an image of God above completing the Trinity?

You might also be interested in the use of the golden ratio of the painting with the tree whilst the bird, hand, bowl divide the picture in two. Piero was like Da Vinci painting as a way of truth rather than for art. Piero was a mathematician this is part of the purpose of the work. A contemplation of the form of the world inside the world of appearance. Hence the structure of worship between the keys and the sword for Peter and Paul and God above pouring through the holy spirit (dove). So the ‘archetypes’ are more explicit.

The side panels are here

http://www.museocivicosansepolcro.it/it/museo-di-piero/collezioni

and here is an article giving some context

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/religion/8711641/Piero-wasnt-just-painting-pictures.html

Hi David,

Thanks for this, though I couldn’t find the side panels on the Museo Sansepolcro link.

I think Piero and Da Vinci use mathematics very effectively as a tool for creating striking effects of balance that contribute to the symbolic power of the art. Whether or not they believed that mathematics tells us ultimate truths about the universe, though, it seems clear to me that the meaning and interpretation of mathematics depend on us, our bodies and brain structure, just like any other meaning. We can attribute archetypal significance to mathematical structures and thus use maths to contribute to meaning, but if that then slips into absolute beliefs about the ‘truth’ of those structures we would then be unhelpfully projecting the archetypal process. I can appreciate Piero’s archetypal use of mathematics as well as of other forms of symbology without either agreeing or disagreeing with the further beliefs he may have held about it.