It’s about time we had some more visual art on the site. Norma Smith did a series of blogs on paintings during the first year of the site’s existence, but since she stopped doing those we’ve had very little art. I’m going to try to post occasional art blogs about paintings I find meaningful in relation to the Middle Way, but others are welcome to contribute likewise when they feel inspired.

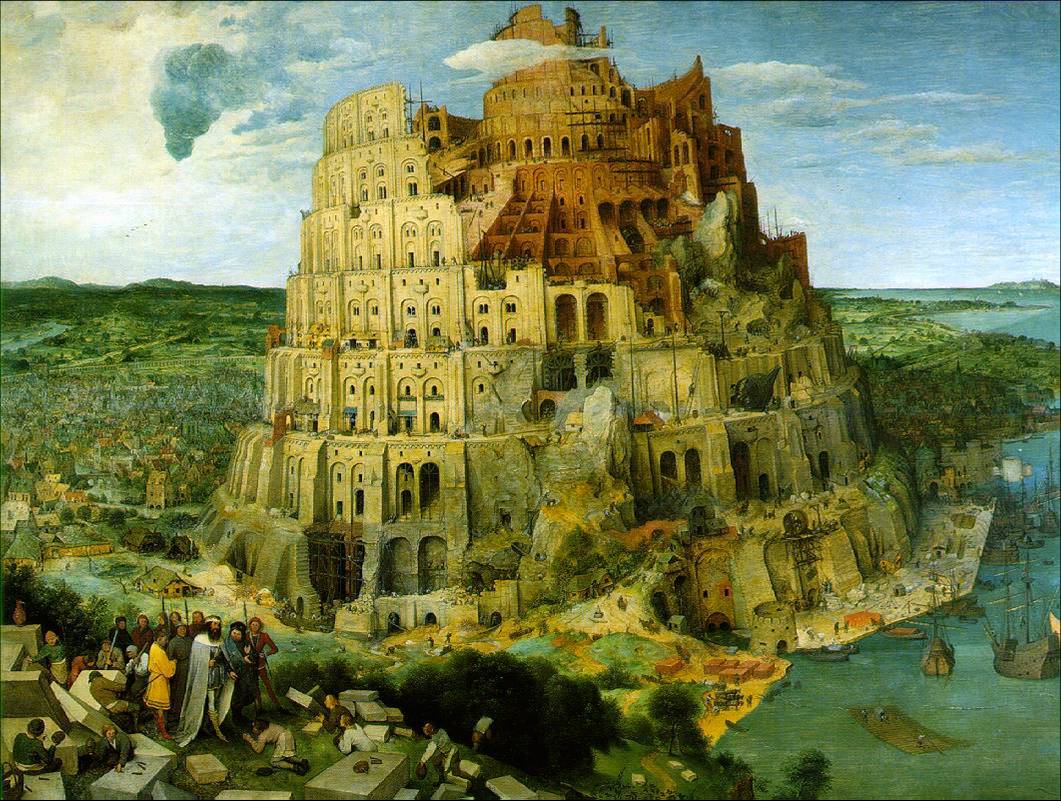

The picture I’m going to look at is Bruegel’s Tower of Babel (click picture below to enlarge).

The painting depicts the building of the Tower of Babel, as described in Genesis 11. The story (for the benefit of anyone unfamiliar with it) is that in ancient times people all spoke one single language. They gathered in one place (Babel, i.e. Babylon), developed brick-making, and built a city. They set out to build a tower into the heavens. God saw them doing this, and complained “now they have started to do this, nothing will be beyond their reach.” So to stop them, he confused their language and dispersed them, so that they would not be able to work together in building the tower.

Bruegel imagines the tower under construction, under the command of a king, and using technology very much of his own time rather than of ancient Babylon. But for us the anachronism can be a good prompt to understand the painting symbolically, not as a depiction of a historical event. The Tower of Babel has often been interpreted as symbolic of pride: of humans trying to be like God, but not succeeding, and being punished for their hubris.

But we could go a bit further than this in interpreting the painting. It’s a depiction of a massive construction project: think of the Three Gorges Dam. The planners think they’ve got it all worked out, but fail to take into account the unknown unknowns. What are the conditions that really operate when you build that high? It points out a limitation in utilitarian-type thinking which fails to take into account the degree of human ignorance.

But the story also closely links the planning and the over-ambitious goal with language, and in doing that it can represent the close relationship between representational language and goal-orientation in the left hemisphere of the brain. The tendency of the left hemisphere, when it gets over-dominant and neglects the Middle Way, is to think its beliefs are completely accurate, and that its words correspond with reality. The ‘dispersal’ of the builders and the loss of a single language could be related to the recognition that we don’t communicate in that way: our language has no absolute meaning, but rather its meaning depends on what is experienced by each person. The linguistic assumptions in our big plans are thus dangerous and precarious ones. We think the words in our plans must correspond to things in the world, but they may not do so at all.

Bruegel represents the pomp and power of the organising king with his big plan in the bottom left-hand corner, with his servants prostrating themselves before him. But given what virtually everyone viewing the painting will know about the subsequent fate of his construction, this power seems empty. Like Donald Rumsfeld before the Iraq War, he probably throws all warnings about his tower into the waste paper basket, but things turn out rather differently from his obsessive projections.