How do we understand the role of saints in relation to the key idea of the Middle Way – i.e. to avoid metaphysics? After all, these people had very real virtues that many people testify to, yet they were steeped in metaphysics. Aren’t they a counter-example to the thesis that avoiding metaphysics is morally and spiritually preferable? I don’t think so, but to explain why will require a bit of exploration of an example. For my example I have chosen St. Francis, as I read his biography (by Adrian House) a little while ago.

St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) is a figure that it is easy to admire, or at least respect. He wasn’t a grisly martyr or a captain of the inquisition, but rather he was renowned for his humility, tranquillity and wisdom. As an alternative to the corrupt monastic orders of his day, he created a new brotherhood and sisterhood – the Franciscans and the Poor Clares. He also had intense religious experiences, and courageously tried to bring peace to Egypt during a Crusade by crossing the enemy lines and speaking directly to the Sultan that the Christians were fighting. However, throughout that time he remained completely obedient to the Holy Catholic Church and its metaphysical dogmas.

Didn’t Francis do pretty well on metaphysics? And how could he possibly have “avoided” metaphysics? Francis can here represent a host of other figures, throughout the ages and including the present, in a similar position. The idea that we should consider the influence of metaphysics on such figures to be a bad thing rather than a good thing requires a complete reassessment of our ideas about religion and morality, to an extent that many people find incomprehensible.

It will become comprehensible only when we look a bit more closely and carefully at what is involved in the idea of a person having a metaphysical belief. The idea of committing one’s life to a metaphysical belief is one that has become dominant, not only in religion, but also in some areas of politics, art and beyond: but it is delusory. Somebody who ran their life entirely on the basis of a belief that bore no relationship to experience would not be able to respond to their experience, because they would have no models available to them that were compatible with that experience. Experience throws up all sorts of specific practical challenges that require specific beliefs. All-encompassing metaphysical beliefs are no use for this. Knowing that God is love does not help you identify which mushrooms are poisonous, or even which friends you should trust.

Thus, we can be confident that even the most committed saint does not in fact run their lives on the basis of metaphysical beliefs. Instead, they have a number of models of the world around them that they construct either directly from experience, or from the models given to them by others in the course of their socialisation and education. Included in these models are metaphysical ones. Deeply rooted in a metaphysical belief is the idea of the ultimate importance of that belief: but experience does not bear out such a claim of self-importance.

In the case of St. Francis, then, we would expect his main beliefs to be ones about the practical world in which he lived: for example, the lasting and solid nature of objects such as walls and tables; beliefs about social relationships and of what sorts of behaviour were acceptable and unacceptable in medieval Assisi; or beliefs about the political rule of the Dukes of Spoleto and the negative effects of questioning their power. The fact that Saint Francis also believed strongly in the existence of God, that Jesus was the Son of God, and that the Pope was the representative of God on earth, did indeed have important effects on Francis’s life, but that does not mean that they were the only or even most practically important beliefs that he held.

Let us take St. Francis’s virtues of tranquillity, humility and wisdom, which Francis himself (and presumably most modern Christians) would attribute to his strong belief in God, Christ and the Church. Yet Francis’s actual experiences relating to these things would have come through prayer, in which he may have attained highly integrated states, from a sense of meaningfulness in his whole life, and through encounters with the Church, its clergy and the Pope. When having a religious experience, Francis would have strongly associated this with metaphysical beliefs – but the meaning of this experience was a direct physical one, as we can see from the embodied meaning theory. The experience itself could not have been based on metaphysical ‘truths’, because these ‘truths’ were themselves constructed through metaphor on the basis of prior physical experience. Rather, the metaphysical ‘truths’ were a rationalisation created by the habitual thinking of his society and projected onto his religious experience. Francis’s encounters with God would be encounters with an archetypal symbol of integration in his deepest experience, not a metaphysical belief appealing to concepts. His religious experiences were so physically immediate that he is said to have received the stigmata (marks of Christ’s wounds) and to have walked on burning coals unharmed: whether these happened in a more literal or a more symbolic way we do not know, but if they did happen in a way that others witnessed they can hardly have been the result of a merely abstract metaphysical belief – rather of an experience that possessed his entire being.

So Francis’s virtues would have come, not from his metaphysical beliefs, but from his more basic experience of integration. Temporary experiences of integration, especially when experienced deeply on a regular basis, as they are by some meditators, are a wonderful source of tranquillity, of a kind that could keep Francis content with extreme self-imposed poverty. They are also a source of wisdom, because they provide a wider perspective on experience that can help judgement take into account a wider range of conditions. This experience of integration would also keep the edges of his cognitive models supple and malleable in a way that would enable him to accept correction by others and recognise his own limitations: in other words give him humility.

Francis was a saint not because of, but despite, his metaphysical beliefs. The very fact that he could emerge in the context of medieval Catholicism tells us something of the strengths of that tradition. The virtues of integration were admired, even though there was a good deal of confusion about their source. It was possible, in fact, to believe that metaphysics was good and ordinary physical experience was evil – the exact opposite of what I would argue to be the actual case, and to make that belief stick. But at the same time, people would actually make most of their judgements based on ordinary physical experience – including many of their moral and religious judgements.

How has such a belief been made to stick for so long? I can only suggest that this is because it had an adaptive value in maintaining group loyalty. People maintained their loyalty to the Church in medieval times, and this loyalty helped them to live together with limited conflict, as well as uniting them against enemies that would otherwise have defeated them. There is nothing better than an apparently unquestionable belief for maintaining loyalty and group identity.

However, this apparently positive effect of metaphysics comes at a price. We can see that price illustrated in Francis’s own life. Unable to question the Pope’s authority, he remained at the mercy of papal whims. Deeply committed to the ideal of poverty as an end in itself based on the self-sacrifice of Christ, Francis got into conflict with other early members of his order who wanted a slightly less ascetic lifestyle in which a few more of their needs could be met. Francis had his weaknesses, and we can trace each of these directly to an appeal to metaphysical authority.

More widely, the medieval society in which Francis lived suffered from its obsessive relationship to metaphysics. Conflict was created both internally (e.g. putting down of heresies such as the Cathars) and externally (e.g. the Crusades). The scientific advances that had been made in Classical times were largely forgotten, continued and developed only in the (at that time) slightly less rigid Islamic world. Political rule remained autocratic, society stratified, education and learning extremely limited. New ideas were dangerous and ideological change very slow. The medieval world is a warning to us of what a society dominated by metaphysical commitments might be like. Nevertheless, it was neither unchanging, nor incapable of creating striking innovators like St. Francis.

I hope from this example, the possibility of avoiding metaphysics might become a little clearer. Metaphysics is not a basic set of assumptions that we can’t avoid, as some claim. We do often make such basic assumptions, but it’s our business to question them and hold them provisionally as far as we can. Nor are metaphysical beliefs responsible for our virtues. We do all have them, to a greater or lesser extent, and will not be able to give them up all at once. However, an incremental approach can work in shifting our energies from metaphysical beliefs to non-metaphysical ones.

St. Francis himself may have got about as far as he could in avoiding metaphysics, given that he lived in such a deeply metaphysical society. So part of the effort in avoiding metaphysics may take place at a social and political level. For example, if we were no longer indoctrinated into metaphysical views from early childhood, this would no doubt help us in avoiding them. However, each of us is placed in a situation now in which we have certain metaphysical influences and certain non-metaphysical influences. We need to work with whatever we have, from wherever we start.

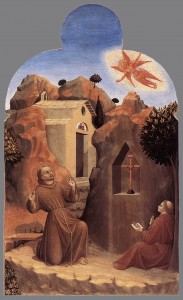

But there is no reason today why we should not be inspired by the virtues of Saint Francis. Every time I visit the National Gallery in London I enjoy the paintings of his life by Sassetta, which are all part of the San Sepolcro Altarpiece (one of these illustrated). The saint has a symbolic value for me that I find difficult to explain, beyond a broad understanding in Jungian terms that he is an instance of a Wise Old Man archetype. Somehow seeing fifteenth century depictions of him strikes much deeper than any later depiction could do.