It’s almost a simplistic metaphor, but … picture three boxes: order, disorder, reorder. … [I]f you read the great myths of the world and the great religions, that’s the normal path of transformation.

–Richard Rohr

This blog post is part two of a three-part series inspired by the above quote by Richard Rohr (shown in the photograph on the right). If you’ve not read part one I recommend doing so now so that you appreciate the context of Rohr’s words and how they might apply to the great myths of the world. Here, in this post, I consider what Rohr’s three-box model might have to say about political polarisation in society, and what its limitations might be. In the third and final post I will frame my own ‘spiritual’ development in terms of Rohr’s model and make some concluding remarks.

This blog post is part two of a three-part series inspired by the above quote by Richard Rohr (shown in the photograph on the right). If you’ve not read part one I recommend doing so now so that you appreciate the context of Rohr’s words and how they might apply to the great myths of the world. Here, in this post, I consider what Rohr’s three-box model might have to say about political polarisation in society, and what its limitations might be. In the third and final post I will frame my own ‘spiritual’ development in terms of Rohr’s model and make some concluding remarks.

A political perspective

What conservative people want to do is just keep rebuilding the first box, “order, order, order,” at all costs, even if it doesn’t fit the facts or fit reality. … So many progressive, academic, liberal, educated folks, they just keep sloshing around in the second box and almost resist any sense of order.

So, the context in which Richard Rohr is speaking here is that of the political situation in the USA: dominated by two parties, Republican and Democratic, conservative and liberal, traditional and progressive. We may have a different national political dynamic here in the UK, perhaps slightly less polarised, but it is broadly similar and people tend to position themselves one way or the other on the conventional political spectrum.

From Rohr’s choice of words here, he sees the difficulty with the individual maturing politically if that individual strongly identifies with one political orientation or the other. If you identify with the conservative ideology then you feel as if you’re being constructive in rebuilding the “order” box over and over, but in adhering so rigidly to the absolute belief that order must be maintained at all costs you’re blocking the path towards a more provisional, nuanced situation where you can better address conditions.

Conservative over-confidence?

I’ll tentatively suggest that the recent ‘Brexit’ result of the UK referendum (on continuing membership of the European Union) represents an example of this. I have to admit a specific difficulty here, though, as part of the large minority that voted to remain in the EU. The echo chamber and filter bubble of social media mean that I’m rather out of touch with views that might help me to understand why a majority voted to leave the EU in the referendum.

From the limited discussions I’ve had with ‘Brexiteers’ I get the impression that there’s a desire to put the country into a new order box that very closely resembles the one that existed before the UK entered the EU in the early 1970s (before my time!). Not that we were experiencing a period of disorder during the years of EU membership – and there was a long stretch of ordering along neoliberal lines during the Thatcher years – but there is a belief that once we’ve got through the process of leaving the EU the country will be able to construct a better order without ‘interference’ from Europe.

From the limited discussions I’ve had with ‘Brexiteers’ I get the impression that there’s a desire to put the country into a new order box that very closely resembles the one that existed before the UK entered the EU in the early 1970s (before my time!). Not that we were experiencing a period of disorder during the years of EU membership – and there was a long stretch of ordering along neoliberal lines during the Thatcher years – but there is a belief that once we’ve got through the process of leaving the EU the country will be able to construct a better order without ‘interference’ from Europe.

Of course I’d argue that Brexit does not represent an improvement, that it is not a synthesis after the years of pre-1973 order and the perceived disorder of the EU years; I personally view it as a step backwards to an outdated form of political order (that probably wasn’t so great anyway back then) and seems unlikely to adequately deal with conditions now. But then my political inclinations dispose me towards that kind of view. I imagine the stereotypical conservative Brexiteer to be clinging to a fragile absolute view (“it is right that the UK determines its own path” or “our greatest problems are caused by immigrants”), and that view cannot be properly examined because the lack of incrementality means that it wouldn’t survive the examination process… fear of disorder (where simplistic, absolute beliefs are recognised as being inadequate, or even harmful) holds them from making political progress.

Progressive pitfalls?

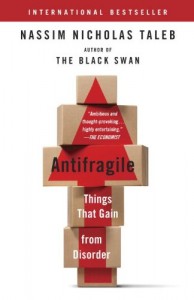

On the other hand, if you strongly identify as a progressive, as a liberal, then there’s the danger of only being able to see tradition and the existing order as an absolutised evil, and rejecting it wholesale, whether or not it actually addresses conditions. I’ve found the Taleb’s perspective to be of use here in helping me to challenge my own liberal, progressive views – for example, in his book Antifragile he points out that the longevity of a product, tool, book, idea or ideology is positively correlated with its age, since the products, tools, books, ideas and ideologies that don’t address the conditions of the real world don’t survive! Time, using his language, is the best creator of antifragility, as in the course of time unexpected events eventually occur and demolish the things that were fragile to that occurrence. This is also known as the ‘Lindy effect‘.

On the other hand, if you strongly identify as a progressive, as a liberal, then there’s the danger of only being able to see tradition and the existing order as an absolutised evil, and rejecting it wholesale, whether or not it actually addresses conditions. I’ve found the Taleb’s perspective to be of use here in helping me to challenge my own liberal, progressive views – for example, in his book Antifragile he points out that the longevity of a product, tool, book, idea or ideology is positively correlated with its age, since the products, tools, books, ideas and ideologies that don’t address the conditions of the real world don’t survive! Time, using his language, is the best creator of antifragility, as in the course of time unexpected events eventually occur and demolish the things that were fragile to that occurrence. This is also known as the ‘Lindy effect‘.

It is tempting for me to think that the Middle Way would involve a liberal, progressive politics – but since it seems to me like such an obvious, certain fact the Middle Way itself suggests that it is a belief worth critically examining in significant detail. The work of Jonathan Haidt on what he calls ‘moral foundations theory’ looks for common ground between the conventional camps of the political divide, which might be useful in finding a middle way that better addresses the current political conditions that we find ourselves in. The idea of synthesis also suggests that a better way lies beyond the dualism of conservative and progressive, and the Middle Way is a promising tool to guide us in examining and integrating our desires, beliefs and meanings.

There’s also the problem of progressives taking the order-disorder-reorder model and appropriating it into an absolutised form. Consider, for example, the Russian revolution. The old order of the Russian tsars collapsed in the disorder of the first 1917 revolution, and eventually the one-party state of the Soviet Union emerged from the disorder. The party constructed the history as an inevitable progression from order, through disorder, to re-order – and then stifled any political attempts to challenge the re-ordered state by stating that history had run its course and the inevitable end-state had been achieved. In political revolutions the dis-ordered period is lasts a relatively short time – a likely sign that it’s not going to lead to a more synthetic, re-ordered situation but instead to more of the same order in a different guise. (Aside: see this excellent article by Nicky Case for more on the perils of and alternatives to political revolution.)

There’s also the problem of progressives taking the order-disorder-reorder model and appropriating it into an absolutised form. Consider, for example, the Russian revolution. The old order of the Russian tsars collapsed in the disorder of the first 1917 revolution, and eventually the one-party state of the Soviet Union emerged from the disorder. The party constructed the history as an inevitable progression from order, through disorder, to re-order – and then stifled any political attempts to challenge the re-ordered state by stating that history had run its course and the inevitable end-state had been achieved. In political revolutions the dis-ordered period is lasts a relatively short time – a likely sign that it’s not going to lead to a more synthetic, re-ordered situation but instead to more of the same order in a different guise. (Aside: see this excellent article by Nicky Case for more on the perils of and alternatives to political revolution.)

It seems likely, on an individual level, that adherence to a dogmatic left/right ideology is an impediment to our own maturation politically, as well as spiritually (whatever that means – more on this in the final part of this series). There’s a clear link here with the very Middle Way-ish idea of looking for a synthetic approach to dealing with apparent dilemmas: the thesis and the antithesis initially clash, but through some difficult process the two seemingly opposed ideas are somehow brought together into a more complex new whole. The practice of critical thinking, and the processes by which we can encourage integration are prominent in the Middle Way: see this post by Robert about integration, for example.

- Continue to Order, disorder, reorder – Part 3

- Go back Order, disorder, reorder – Part 1

Featured image of ballot boxes created using an image from pixabay.com (License: CC0 Public Domain)

Photograph of Richard Rohr from wikimedia commons (License: CC0 Public Domain)

EU/UK flag graphic and photograph of revolutionary fresco courtesy of pixabay.com (License: CC0 Public Domain)