I have been thinking recently about the Fall – no, not the leaves falling off the trees, in American parlance. I mean the story in the book of Genesis of the Bible, about how Adam and Eve ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, then were expelled from the Garden of Eden by God. Just mentioning this story may raise the hackles of secularists, who associate it with metaphysical dogma. However, I think there is an important distinction to be made between metaphysical claims, which are dogmatic, and stories and symbols, which are not. To make a claim like “Adam and Eve made all humans sinful” is metaphysical, and we can see the negative effects of the Christian dogma of Original Sin in terms of psychological conflict. However, to tell and re-interpret the myth of the Fall so as to relate it more usefully to experience is a different matter.

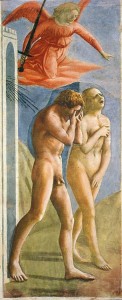

The myth is a potent one. Take this very famous picture by Masaccio of the expulsion from Eden. For me this communicates a very basic experience of suffering and links it powerfully to a sense of exclusion. The story is exploring the meaning of human suffering through creating a story about its causes. Obviously, the way these causes are symbolised is to some extent dependent on the culture of the early Hebrews in which the story developed. However, one would also expect it to tap into more universal human experiences. How we interpret the story in terms of these is something we can play around with. I’m going to offer an interpretation which I think helps to relate the story to universal human experience. That doesn’t mean that I think that’s what the story is “really” about (the “really” would take us back into metaphysics). Rather it’s an interpretation, which I take responsibility for as such.

Let’s think about the basic elements of the story. It divides roughly into three: (1)God creates the Garden of Eden, (2) Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit, and (3) then they are expelled.

If we take a Jungian interpretation of God and his meaning, he represents the integrated psyche, just as a Buddhist mandala does. God is a represented idealised form of how we would be if we were entirely free of conflict, internal or external, and we may associate this symbol with people we know or have heard of who may have got further on this road than we have – Wise Old Men and Wise Old Women. The Garden of Eden, said to be created by God, bears a similar interpretation. It is an idealised symbol of complete contentment through full integration.

However, this garden-mandala contains the seeds of conflict – the tree of knowledge of good and evil. I think one helpful way of interpreting this would be as the ego, or the obsessive function of a detached left hemisphere of the brain. When we eat the fruit (develop the representational functions of the left hemisphere) we gain power and insight because we are able to manipulate the world to our own ends far better than we were before. We can use language to make plans, instructions, warnings etc and communicate them to others. We are capable of gaining an increasingly coherent view of the world in which we act. However, this ability also comes at a price – the tendency of the left hemisphere to absolutise, to believe that it has the whole picture, and to turn its beliefs into metaphysical ones. This might be thought of as ‘knowledge of good and evil’ because of the ego’s tendency to accept and reject things dualistically, thinking of what it happens to like at the moment as ‘good’ and what it dislikes as ‘evil’.

By eating this forbidden fruit, then, we create suffering as well as power, because we exclude ourselves from the degree of integration between the hemispheres we might have otherwise. We emerge from an undifferentiated and implicit awareness into a world of concepts – a process that can be disorientating and alienating. We have been thrown out of the garden because we no longer feel whole in the sense that we might, and yearn for a missing integration.

One of the early church fathers, Irenaeus, described the sin of Adam and Eve as felix culpa, a ‘happy sin’. This suggests that he was getting to grips with the contradictions involved in the Fall. We feel shut out, but we also feel empowered by the ego and its associated conceptualisations. He perhaps implicitly recognised that the ego is not a bad thing to be destroyed, but the basis on which we can develop further. However, stretching the ego so as to gradually dilute its weaknesses requires effort and practice: we can’t rely on a salvation from the effects of the Fall from Christ, as the metaphysical doctrines of Christianity have it.

The story of the Fall is such a basic part of Western culture, that it would be a great shame to merely shut it out by dismissing it as ‘untrue’, as some secularists appear to do. ‘Truth’ is really not a relevant test to apply in understanding what this story – or any story – has to offer. I would suggest that the Middle Way here involves finding creative ways to engage with it and harness its power – whether that is through the kind of interpretation I am suggesting or some other way. Even if we also recognise its limitations, every myth can speak to us in some way.