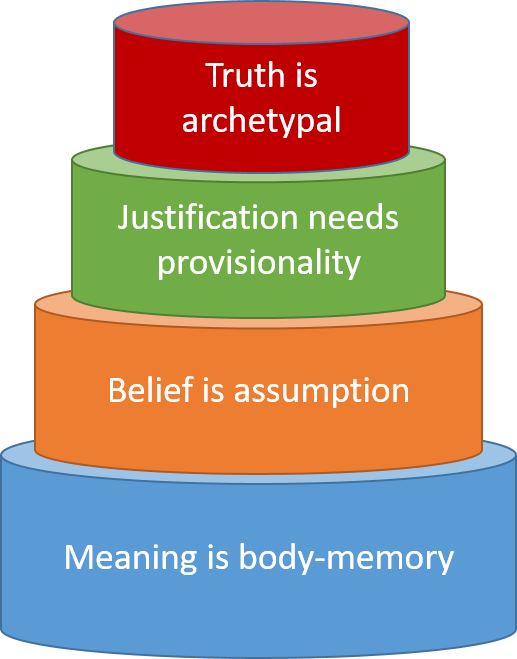

I’m always looking for new ways to get across the key points of Middle Way Philosophy in a compact list that can be readily referred to. The Five Principles on which our summer retreat this year will be based (scepticism, provisionality, incrementality, agnosticism, integration) are one way of doing this, but these five principles focus on qualities to cultivate or use in judgement, rather than on the distinctive world-view they emerge from. So here’s a new attempt to distil that world view into four very brief slogans:

- Meaning is body-memory

- Belief is assumption

- Justification needs provisionality

- Truth is archetypal

The explanation of each that follows will no doubt be rather compressed. However, the main idea of this blog is to encourage you to see these points as interdependent (each building on the previous ones), and to at least glimpse how they challenge much conventional thinking and offer new ways forward for humans stuck in that thinking. For more details on this whole way of thinking, please see first the introductory videos, then the Middle Way Philosophy books.

1. Meaning is body-memory

The embodied view of meaning tells us that meaning is an accretion of memory. But by ‘memory’ here I don’t anything on the analogy of data-storage which people too often use to try to understand memory. Rather, whenever we encounter a new experience, we create new synaptic links connected to our whole body’s active engagement in that experience. That experience may involve associating words or symbols with the experience, and when we are prompted by similar words, symbols, or other associated experiences in future, we mildly re-run the synaptic connections associated with it. We thus lay down layer after unconscious layer of memories that then provide the basis of meaning-association in future, and even quite complex or abstract language draws on this embodied experience to be meaningful, via the medium of metaphorical constructions. Think about the most abstract language – a scientific paper, say, or a company board meeting. The meaning of all this language, however abstract, still depends on your body. When you have no body memories to connect with it, you cease to understand what is being said.

2. Belief is assumption

The dominant tradition in philosophy and science, which then influences the way people usually talk about their beliefs, is to think of them as explicit, but explicit beliefs are the tip of a very large unconscious iceberg. Most of our beliefs are a matter of what we assume, rather than what we have explicitly said. If you said you were hungry and then started looking at the sandwiches in a café, it would not be unfair to conclude that you believed that a sandwich might address your hunger, even though you didn’t explicitly say such a thing. Yet, strangely enough, most of the established thinking about how to live our lives just offers explicit reasons for believing one thing rather than another, rather than trying to work with what we actually assume. It is not reasoning (which always proceeds from assumptions) that will help us make our beliefs more adequate to the situation, but rather greater awareness of the assumptions with which we start to reason.

But we can only believe what we first find meaningful in our bodies, so the second point depends on the first.

3. Justification needs provisionality

How do we tell how well a belief is justified? That’s a question at the core of all the judgements we make in everyday life, in ethics, in science, in politics or elsewhere. The traditional answers all involve explicit reasons: for example, that a certain action is wrong because it says so in the Bible, or a certain scientific theory is correct because it can be supported by evidence. But we are constantly subject to confirmation bias, all of us living in our own little echo-chambers in which we seek out what we want to hear. The old ways of justifying our beliefs are not enough by themselves. We need to take into account the mental state in which the judgement is made too, to incorporate psychology as a basic condition in our reasons for adopting one belief rather than another. If we can hold a belief provisionally, so that we can consider possible alternatives, we are better justified than if we do not.

The mental state in which a belief is held is inextricable from the set of assumptions that support that belief. We can hold a belief provisionally if we find alternatives sufficiently meaningful (using our imagination). In the traditional ways of thinking dominant in philosophy and science, this way of justifying our beliefs cannot be taken seriously, because meaning is assumed to depend on belief and belief to depend on justification. In that way of thinking, reasoning comes first rather than the mental states in which the reasoning takes place, but this mistakes the tip for the whole iceberg. The third point thus depends on the first two.

4. Truth is archetypal

People are typically obsessed with ‘truth’, ‘the facts’, God, nature, ontology, ultimate explanations. Surely these things are important? Well, only in the sense that they are meaningful to us, not in the sense that we need to build up justifications of our beliefs by depending on them. If we think of ‘Paris is capital of France’ as true and ‘Paris is the capital of Mongolia’ as false, that is usually a kind of shortcut for the thought that the first is much better justified than the other, and that we assume it in practice. But, according to the third point above (justification needs provisionality), to be justified in believing that ‘Paris is the capital of France’ I need to believe it provisionally, that is to be able to consider alternatives. Whether I actually do this or not, claiming that it is true or false adds nothing to that justification apart from cutting off the provisionality, making it the final story and closing off any further thought or discussion on the subject. Claiming that it is true or false thus actually seems to undermine one’s justification.

Nevertheless, we can respect the motive of those who seek to establish the truth (which they will do best by considering the justification of a belief against alternatives – by doubting the truth of their claims rather than asserting it). Truth can thus still be a kind of symbolic inspiration or archetype (see this blog post for examples), and not claiming to possess archetypal truth a mark of fully respecting it. Just as we need to avoid projecting an archetype on someone else by thinking that they are God, or the perfect woman, or whatever (even though we may also appreciate ideal artistic depictions of God or of the feminine) we need to recognise truth as a symbol that we find meaningful in relation to our body-memory, without projecting it onto a particular set of words that we take to be ‘true’. Instead, whenever there is a discussion about whether we should hold one belief rather than another (in science, politics, ethics etc.) we can focus on justification.

We could not make sense of truth being archetypal if we did not separate meaning (point 1) from belief (point 2), recognising that meaning precedes belief rather than the other way round, and that we can find truth meaningful without believing that we have it. It’s also precisely because of the need to maintain provisionality about our beliefs (point 3) that we cannot justify claims of truth.

This view of truth can potentially transform our view of science, ethics and religion: whether we are talking about scientific facts, the good, or God, we can respect the motivations of those who value these things without accepting that any of them are actually possessed in a particular verbal formula.

The four points and the Middle Way

The Middle Way means a practice of seeking justification for our beliefs in provisionality rather than in consistency or evidence alone. To stay in this provisional zone, we avoid the absolutes of claiming truth on the one hand or falsity on the other. To do this in practice requires our mental states to be provisional, which is just as much a matter of our emotions and body as of our reasoning. It’s not a question of aiming to be in some wonderfully enlightened mental state, but simply of judging better every time by being less confined by our personal echo-chambers than we might otherwise be.

In connection with the founding story of the Buddha from which the term ‘Middle Way’ derives, we need to focus not on the final state that the Buddha supposedly achieved by using the Middle Way, but how his judgements at each stage reflected provisionality and enabled him to move beyond the rigid assumptions of those around him. First he needed to leave the palace with its rigid ‘truths’, then also move beyond the religious world of spiritual teachers and ascetics with their ‘truths’ (which also declared the world ‘false’). If we unpack what is required for the Buddha to go through this process at each stage, it involves maintaining a sense of the meaning of alternatives (point 1), developing a greater awareness of the limited assumptions of those around him (not just their explicit views – point 2), and recognising their lack of justification (point 3). If the Buddha had at any point discovered the ‘truth’, this would have halted his progress by ending the story, but instead the story continues – indefinitely.