I am sometimes asked whether Middle Way Philosophy offers a meaning of life, and what it has to say about death. I have often been hesitant in trying to offer perspectives on these kinds of questions, because there is such a long tradition of unhelpful metaphysical speculation about them. However, I think the Middle Way can be applied helpfully here, if only to challenge that tradition of speculation and point us back to experience. This post is the final chapter of my new introductory book, Migglism, which should finally be published within a week or so now. I have added it to the book recently in response to a useful suggestion from Mike Fedorski.

If we are to avoid metaphysics, there can be no meaning to life as a whole beyond the meaning that we experience. That may sound like a familiar truism – that the meaning of life is just what we make it. However, the Middle Way implies a couple of other points here as well. Not only is there no absolute metaphysical meaning to life, but there is no denial of meaning either – life is not meaningless, but rather full of the meaning we find in it. The other crucial point is that meaning is an incremental matter. We are not going to find meaning all at once, as a solution to all our struggles to find meaning. Rather, we can gradually increase the meaningfulness we encounter in life.

I suggest, also, that this incremental meaningfulness is found with our degree of integration. The meaning and value we find in life as a whole, after all, need be no different from the meaning and value we find in different specific things in life: for example, the momentary value we find in stroking a pet, or embracing someone we love. The problem with getting a meaning of life as a whole from these experiences is not that they are not meaningful in themselves, but that this meaning is momentary, and perhaps in conflict with the lack of meaning we may experience at other times. When I’m feeling frustrated in the office later on, the embrace of the early morning is already gone from my awareness.

Thus it seems that we should gradually find more meaning in life the more we become integrated, whether that integration is of desire (bringing our energies together), meaning (bringing our sense of significance together), or belief (bringing our views of the world together). The more we are integrated, the less likely we are to be caught up in inner conflict and frustration, and thus the more likely we are, on average and on the whole, to find life unified, meaningful and fulfilling.

This fulfilment is always relative to the circumstances we find ourselves in. If, for example, you are a citizen of Aleppo being constantly bombed by Syrian government forces during the Syrian civil war, you will spend most of your energy just dealing with extremely difficult and stressful external conditions. However, there will still be more or less integrated ways that you can respond to these conditions. The meaningfulness of your life in such circumstances could only really be measured against what it might have been in different circumstances, whether those circumstances were reasonably secure or even over-protected – not against some abstract absolute. Some people can be destroyed by difficulties, while others gain an intense sense of fulfilment by responding in an integrated way to them.

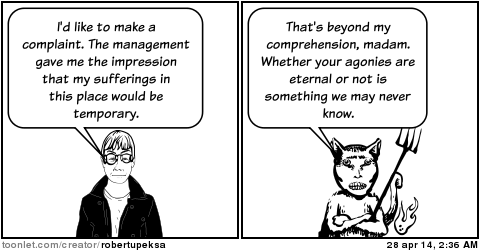

One of the basic conditions of difficult circumstances in life is the ever-present threat of death. Like other conditions in life, it seems that the key question is whether we can accept death and respond to it in a balanced way, rather than anything about death itself. Speculation about death itself is just a distraction from the Middle Way – whether such speculation involves beliefs about an afterlife (or reincarnation), or the denial of such beliefs. Our living experience gives us no purchase at all in justifying either affirmation or denial of afterlife beliefs, so, for example, the amount of debate about rebirth that distracts Buddhists who are otherwise interested in practising the Middle Way is rather unfortunate.

Death itself seems to be just a condition of life. It is something we are often inclined to forget that it is the temporariness of our living experience that makes it meaningful to us. An eternity of pleasure could be no more meaningful to a breathing, changing creature than an eternity of suffering, as we can only grasp the idea of pleasure or suffering in relation to an experience in which things change. The idea of such an eternity is thus just a symbolic abstraction. In practice, our pleasures are pleasurable and our pains painful only because they are impermanent, and the same could be said for life as a whole.

So, death is just a condition of life. It may be one that causes us anxiety, but anxiety is just another term for conflict between a part of us that is attached to living experience and a part that recognises the inevitability of death. If we can still that conflict, through integrative practice of one kind or another, there seems to be no reason why we should not make progress in stilling our fear of death.

I understand the sentiment that leads Dylan Thomas to write

Do not go gentle into that good-night,

But rage, rage against the dying of the light!

I read his poem as a protest against passivity and morbidity. It is possible to be too passive in the face of death, or too obsessed with the question of death. If we swap the immediate experience of living for a mere abstract idea of how we might adapt to death, we are merely distracting ourselves from the full use of the life that is available to us. However, I think Thomas’s mistake is to identify the acceptance of death with one partial feeling we have in life. Instead, I think acceptance of death probably comes through integration of our different desires in life. We do not have to fight against our fear of death, but rather incorporate the energy of that fear into an overall recognition that we can live life better in a full acceptance of its conditions – and those conditions include death.