A simple argument consists of a conclusion supported by reasons (see Critical Thinking 1). However, most arguments are actually constructions that join these simple blocks of argument together in more complex ways. Just as a novel consists of various parallel sub-plots coming together into the conclusion, so arguments may bring several strands together in a great variety of possible patterns to support an overall claim. If you read a comment column in a newspaper, or an argumentative blog, for example, there will probably be more than one simple argument.

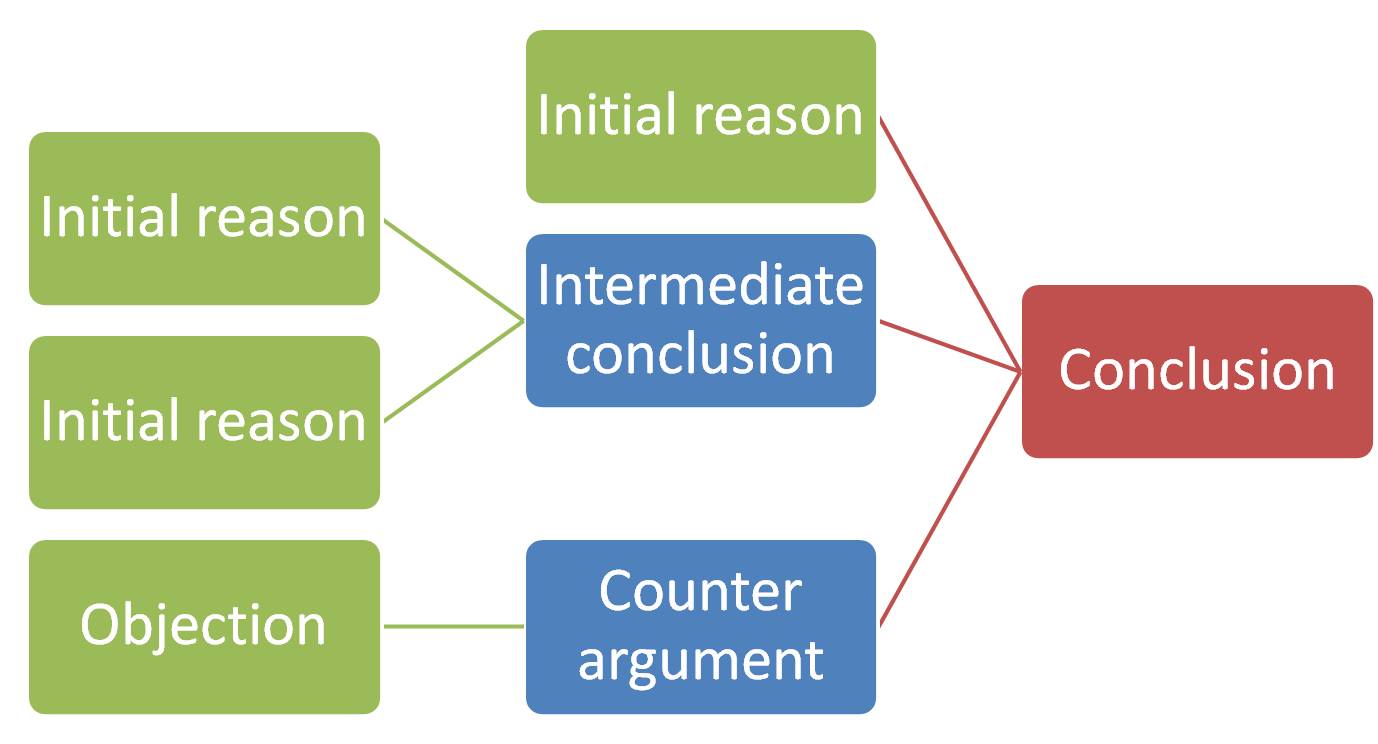

Simple arguments can be joined together in chains in which the conclusion to one argument becomes a reason for the next. The first conclusion us then called an intermediate conclusion. For example, in the following chain argument, the initial reasons are in green, the intermediate conclusion is in blue, and the final conclusion is in red:

Most cats purr when they are stroked.

Purring is a sign of contentment.

So most cats like being stroked.

Felix doesn’t like being stroked.

So Felix is an unusual cat.

Chains can be as long as you want them to be. Having laid out an argument you might also find one of your assumptions being questioned (or anticipate it being so), so you then go back and offer further justifications for your assumption, thus extending the chain backwards.

Arguments can also work in parallel. For example, a list of reasons can be used to support one conclusion, or several chains of argument can all converge on the final conclusion. Complex arguments can also include counter-arguments, where objections are considered and then refuted. The refutation then serves as a reason to support the conclusion.

To make these kinds of arguments clear, diagrams can be very helpful. Austhink have some very useful argument-mapping tutorials if you want to go more deeply into mapping arguments diagrammatically. They sell software for mapping arguments, but it can also be done using Windows SmartArt (examples below) – or, of course, freehand on a piece of paper!

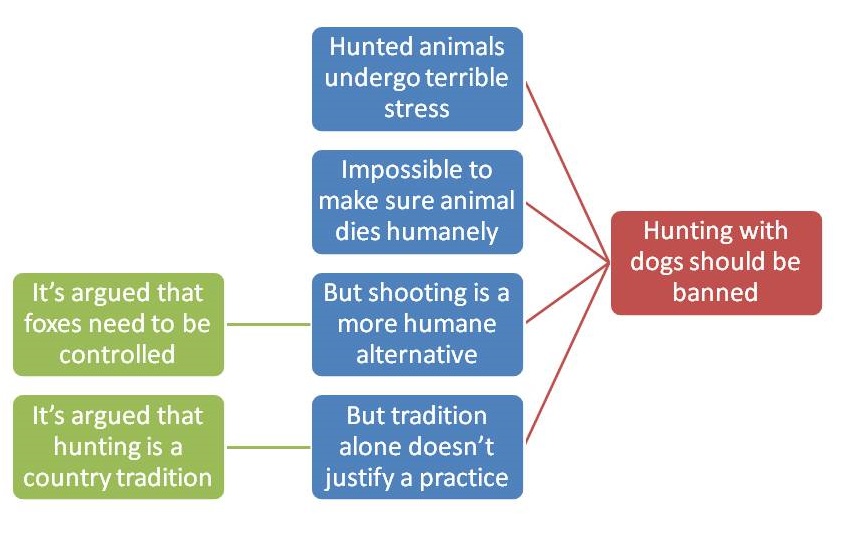

Here’s an example of a ‘list’ style argument with a diagram to illustrate it:

There are all sorts of reasons why hunting with dogs should be banned. Animals hunted with dogs, such as hares and foxes, undergo terrible stress when they are pursued by dogs. It’s impossible to make sure that the animal dies humanely when it’s torn apart by dogs. Fox-hunters argue that numbers of foxes should be controlled, but they can do this by shooting, which is far more humane. They also claim that it is a country tradition that townies could never understand, but merely appealing to tradition does not give justification for a practice.

Exercise

1. Analyse the structure of this argument by stating which sections are the conclusion, intermediate conclusion(s) and initial reason(s). If there are counter-arguments state the objection and the counter-argument.

It is often assumed that world religions all involve different ways of worshipping God or gods, but it can be seen that this is not the case when Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism are counted as religions. These Eastern religions are not focused on God or gods, and the gods that do appear are incidental to them. Scholars of religion have been overwhelmingly influenced by Christian ideas of what ‘religion’ means, but if you look at a wide range of religious practice around the world it becomes clear that the model of religion as belief in God is just one amongst many.

2. Make up an argument (about anything you like) that follows this structure: