During a recent(ish) podcast, in which Peter Goble and I discussed issues surrounding the experience and management of pain, I suggested that the distinctions between mind and body – which have existed in modern medicine – are beginning to be broken down; that scientific medicine was embracing holistic ideas and practices with more than mere lip service. This, in part, has been in response to the apparent rise of ‘holistic’ or ‘complementary’ therapies (I say ‘apparent rise’ because I think that therapies offering alternatives to the mainstream have been popular in one form or another for a very long time). Despite harbouring some doubts about such theories, usually regarding their underlying theories or their general efficacy, I have long thought that the tendency to treat the ‘whole person’ rather than focus solely on specific diseases is a good one. If we take lung cancer, as one obvious example, then it’s right to say that it’s a disease that can be identified in one area of the body and treated locally. If it’s found early enough it can even be surgically removed and the patient can be ‘cured’. All of this can be achieved without much thought for the individual involved, but it shouldn’t be. There are many reasons why a holistic approach should accompany (or rather form part of) the medical approach. A person’s lifestyle or environment can be manipulated to aid recovery, or even help reduce the risk of getting lung cancer in the first place, and the person’s emotional needs should also be considered. Getting lung cancer is not just a physical event; there will likely be considerable emotional effects too – which, like physical symptoms will be different for each individual.

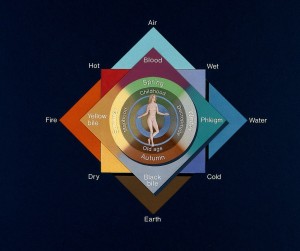

Such things are increasingly being contemplated and acted upon by the medical community, which is interesting when one considers that the humoral model had been doing this for centuries, before being rejected roughly 200 years ago, by the scientific model. From the 10th to the 19th century CE the established medical orthodoxy was based, almost entirely, on the ancient ideas of thinkers such as Hippocrates, Aristotle and Aelius Galen. This system was based on the belief that the human body consisted of four fluids (or humours): Yellow Bile, Pure Blood, Black Bile and Phlegm. Each humour had unique properties and were related to such factors such as Aristotle’s four elements and the four seasons of the year. So, the properties of Yellow Bile were considered to be ‘hot and dry’ meaning that it was related to the ‘element’ fire and the summer season. Phlegm, on the other hand, was ‘wet and cold’ and thus associated with ‘water’ and ‘winter’. Each person had an optimum ratio of these four humours, which was specific to them; personality, emotion and physical condition were all determined by this ratio (or complexion). One’s health was the product of one’s complexion; if the ratio of humours became deranged then ill health would follow. Factors such as environment, food or the position of celestial bodies could all alter the amount of each humour.

the four seasons of the year. So, the properties of Yellow Bile were considered to be ‘hot and dry’ meaning that it was related to the ‘element’ fire and the summer season. Phlegm, on the other hand, was ‘wet and cold’ and thus associated with ‘water’ and ‘winter’. Each person had an optimum ratio of these four humours, which was specific to them; personality, emotion and physical condition were all determined by this ratio (or complexion). One’s health was the product of one’s complexion; if the ratio of humours became deranged then ill health would follow. Factors such as environment, food or the position of celestial bodies could all alter the amount of each humour.

Diseases were not thought to be specific entities in of themselves. Every incidence of disease was specific to the person who was suffering, and thus treatments were tailor made to address the specific conditions that were responsible. If a set of symptoms were thought be caused by a surplus of Yellow Bile, then any treatment would have the opposite properties of cold and wet. Such treatments could include a prescription to change the properties of ones environment or diet, as well as for medical concoctions and surgery. By considering psychology, physicality, lifestyle and environment as deeply interrelated factors, thereby focusing on the whole patient as an individual, humoral medicine was truly holistic. It was impressively versatile too; from Christianity, through the emergence of human dissection, to the enlightenment, challenges to the ancient system came from many sources. Often, such challenges would be integrated into the existing theory. God became the primary cause of disease, causing it and allowing it to spread as a punishment for sin, and new treatments based on chemical experimentation were added to the long list of remedies and concoctions. What did not change, and what was not readily challenged within the mainstream, were the core ideas of the classical scholars. It was widely believed that the work of those such as Galen could not be bettered, only expanded upon (although this too was a matter of debate). Even when human dissection showed that anatomy differed from what Galen proposed (Galen only dissected animals) it was frequently assumed that the anatomist, not Galen, had made a mistake. Some scholars would even alter their descriptions to fit the Galenic sources. Mainstream medicine spent over 1000 years being based on a, largely, unchallenged appeal to authority. Those who dared practise outside of its dogmatic sphere could find themselves the unfortunate victims of persecution.

A combination of factors (theoretical, technological, political & social), occurring up to and throughout the late 18th to the mid 19th century, eventually led to the decline of this long lived classical theory. The emergence of increasingly scientific medical theories led to a general shift in focus from the patient – as an individual to be treated as a whole – to a specific part of the body or an external, disease causing, entity. As such the patient, in many cases, came to be viewed as an incidental part of the disease process. That’s not to say there was a clearly defined shift from the ways of the old to those of the new; there rarely is. Nor was there a move from a wholly holistic practice to one where such considerations were completely absent. Nevertheless, the medical community was becoming increasingly specialised and all to often the human being was becoming lost in the detail.

I’m not going to argue that this process shouldn’t have happened. The tendency to specialise and focus on diseases as distinct entities and specific parts of the body has given us incalculable benefits. If faced with the prospect of a Tuberculosis outbreak, I’ll take the scientific explanation and subsequent course of action over that of a humoral practitioner any day. Similarly, if I ever need complex cardiac surgery and I’m given the option of a surgeon that is warm, kind and empathetic with an above average mortality rate or a sociopath with a rude, unpleasant bedside manner, who has a very low mortality rate, I’ll take the latter every time. Of course, it would be much better if I could have a surgeon who combines the best of both. This might be a bit idealised, and it would be unrealistic to expect every practitioner to experience and radiate the same levels of empathy, just as one could not expect every surgeon to have the same technical skills, but that does not mean it shouldn’t be aimed for. A surgeon would probably not think much of the notion that they should always endeavour to become as technically skilled as they possibly can be, but the suggestion that the same principle should apply to bedside manner might not always be met with enthusiasm. I think that it’s an oversimplification to claim that patient’s are viewed merely as objects rather than individuals but there is some truth to this, as demonstrated by this very funny video (which is only funny because there is more than a whiff of truth, and familiarity for anybody that works in an operating department). I’ve even fallen into such language myself:

‘Are we doing the abscess next’?

Although I’m glad to say, that in my experience, I’ve always (rightly) been pulled up on such utterances by a colleague:

‘We are not “doing an abscess”, we are treating a person who has an abscess’.

I think that there have been many improvements – from wider environmental and lifestyle concerns to the understanding that our physical or psychological conditions cannot always (if at all) be considered in isolation from each other. Pain management services (in Britain, at least) are a good example where services are being integrated, but there is still a long way to go. The provision for the psychological well being of those staying in hospital, for example, is often inadequate (a situation potentially made worse if you also happen to suffer from a mental illness) – of course a positive emotional experience will not fix that broken hip, but it may well assist in your recovery and help prevent you form developing a new founded, and avoidable, phobia of hospitals. There are obviously financial and logistical factors at play here, which can be hard to overcome – but this is not an excuse for the wider needs of patients to be neglected.

Modern medicine has many advantages over humoral medicine. It is demonstrably more effective at preventing and treating disease and it is not based upon such dogmatic appeals to authority. Clearly, there is dogma and there are appeals to authority, but due to the requirements for evidence and expectations for innovation, such dogmas are short lived – perhaps lasting a generation or so, but falling far short of the 1000 years that Medieval medical orthodoxy managed to exist. However, the shift away from the old ideas probably went to far and our focus became too narrow, meaning, in some respects, we have spent the last 200 or so years rediscovering some of the valuable ideas which had become obscured. The Middle Way Philosophy is unapologetically inspired by many, sometimes apparently incompatible, sources; a ‘magpie’s nest of influences’ made up from those aspects of other ideas which, after critical analysis, have been deemed useful. Good science and, by extension, good medicine also does this, but all too often there is hesitation, often borne from suspicion of ideas that do not fit neatly into the current orthodoxy. There are plenty of ‘alternative/ complementary’ therapies that are widely popular and don’t hold up to scientific scrutiny. To dismiss them all, in their entirety, because of this may be a mistake. Yes, such and such therapy might not treat what it says it treats, in the way that it claims, but that doesn’t mean there is no value to be found. If a GP prescribes a contraceptive pill, it will almost certainly work (if used correctly). As far as I know there is not a Homeopathic equivalent to the contraceptive pill, but the extended consultation that one is likely to receive from a Homeopath could provide many other benefits that GP could not hope to achieve in a 5-10 minute consultation. We shouldn’t be uncritically open to all ideas that come our way, or to the ones that are currently in vogue, but neither should we dismiss them out of hand (even if one aspect has already proven unhelpful). This is not easy to do and we will continue to take wrong turns, just as we have in the past. However, in general, I believe that we will continue to move in something like the right direction, albeit in a haphazard, uneven and uncertain fashion. I also believe that the five principles of the Middle Way, and the wider philosophy that emerges from them, are well placed to help us avoid many of the hindrances of the past.

Picture: The four elements, four qualities, four humours, four season. From Wellcome Library, London (CC BY 4.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Hi Rich, and thanks for this thought-provoking and rather brave post about holistic health and healthcare. I say brave because, if you’re a practitioner within conventional medicine, any challenge to clinical conventions may raise a few eyebrows, and even pose something of a risk to one’s career development. I wouldn’t want to overstate the case about the tension that’s still around, but some medical men (ususally men) do exaggerate the dangers of alternative and complementary approaches to disease, and with some justification.

There are indeed not a few quacks out to make a quick buck out of the gullible and the deperate; and some sincere types who think science is an assault on nature by control freaks in white coats who enjoy torturing bunnies.

Ever since I dipped my toe in the medical world in the mid 1950s I’ve been aware of the tension in myself brought about by the sense – born of personal experience in the care of sick people in hospital – that “there’s more to illness than germs, tumours, accidents and wear and tear”, and that ipso (sort of) facto there’s more to recovering health than pills, potions, injections and rummaging about in someone’s insides to find bad bits to cut away.

Most people, I find, have a very incomplete and muddled sense of what makes us tick, and how our organs and systems work together to keep us well, with the whole organism balanced and kept in equilibrium, in an ever changing world. Your allusion to the ‘humours’ how bumpy has been the way to a clear(er) understanding of the body, and its interpenetration with the mind of perception, sensation, thought and emotion, is a unitary field, and also a integral entity with the world, and all the other life-forms in it. I’ve found as a nurse that many patients (who never had to get to grips with humours) are still lost somewhere in that mediaeval mist. Science, for some, is still remote and hard to understand. Which may be why simple and relatively straightforward ideas such as ‘like cures like’ (homeopathy) and the influence of the sun, moon and planets (astrology) are popular and reassuring to some.

In my travels and work in Zambia, and by working and learning alongside Zambians in healthcare, I was struck by how much weight they place on human relationships in the maintenance of health, and in the causology of illness. Traditional healers in Zambia seem to ‘cut to the chase’ in their interrogation of sick people who consult them, by asking the sufferer directly about ‘who’ might be paying a part in the illness. It’s my impression that this isn’t so much looking for someone to blame, more a opening move in an investigation of the patient’s complex social and interpersonal circumstances, which may be a factor in the genesis of illness, and – more significantly – may play a key role in recovery and rehabilitation.

Perhaps this is something we may discuss in this forum? I think I can see how this relates to the Middle Way, but will be much helped if this understanding can be developed collaboratively. I think you and I and other migglers would see this as a very important part of Midde Way praxis, something to be developed, sophisticated and spread more widely.

Best wishes, Peter

Hi Peter,

Thanks for your kind and thoughtful comments. I’m glad that what I have written resonates in some way with your own experiences.

If I were to have a criticism of what I’ve written, it would be that I haven’t related it to the Middle Way explicitly enough. However, I hope that evidence of how it might usefully apply is at least implicit. Further collaborative exploration would be useful to make such points clearer. I especially see the five principles as being key here.

Rich