What psychologists call apophenia—the human tendency to see connections and patterns that are not really there—gives rise to conspiracy theories.

–George Johnson

Today I learned a new term: apophenia, the tendency for humans to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things. I was already familiar with this particular cognitive bias from reading the work of Taleb and a number of different popular psychology books, but I didn’t know that there was a specific term for it. The neologism was coined in the 1950s by the psychologist Klaus Conrad, who considered this aberration in cognition to be a symptom of the onset of psychosis, but more recently apophenia has been recognised as a universal human tendency. In this blog post I will take you on the journey that led me to encounter this term, and I will also grapple with what I’ve learned from the experience, and what it might have to do with the Middle Way.

Today I learned a new term: apophenia, the tendency for humans to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things. I was already familiar with this particular cognitive bias from reading the work of Taleb and a number of different popular psychology books, but I didn’t know that there was a specific term for it. The neologism was coined in the 1950s by the psychologist Klaus Conrad, who considered this aberration in cognition to be a symptom of the onset of psychosis, but more recently apophenia has been recognised as a universal human tendency. In this blog post I will take you on the journey that led me to encounter this term, and I will also grapple with what I’ve learned from the experience, and what it might have to do with the Middle Way.

The background story

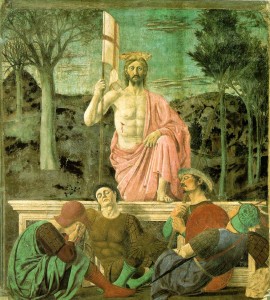

So, yesterday the UK (and many other Western countries) observed the Good Friday bank holiday, which traditionally is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion and death of Jesus Christ. Accordingly the day has—for those who adhere to traditional Christian religious beliefs—a rather solemn nature. On the day before Good Friday the largest supermarket chain in the UK, Tesco, ran an advertisement in some of the print versions of the national newspapers that featured the text “Great offers on beer and cider. Good Friday just got better.” Amusing or offensive? Or something else entirely? Of course it depends very much on your personal perspective.

By lunch-time on Thursday this advert, unlike most other newspaper adverts, had become a national news story in its own right. The BBC website published a story entitled “Tesco sorry for Good Friday beer advert“, featuring a quote from a Tesco spokesperson who said “We know that Easter is an important time of year for our customers. It is never our intention to offend and we are sorry if any has been caused by this advert.[sic]” This story was then widely shared and commented on in the usual social media channels, and it was on my Facebook feed that this story popped up after a friend had ‘reacted’ it. If you’ve got this far and are still not sure why anyone might have taken offence, follow the above link to the BBC news story and read it.

By lunch-time on Thursday this advert, unlike most other newspaper adverts, had become a national news story in its own right. The BBC website published a story entitled “Tesco sorry for Good Friday beer advert“, featuring a quote from a Tesco spokesperson who said “We know that Easter is an important time of year for our customers. It is never our intention to offend and we are sorry if any has been caused by this advert.[sic]” This story was then widely shared and commented on in the usual social media channels, and it was on my Facebook feed that this story popped up after a friend had ‘reacted’ it. If you’ve got this far and are still not sure why anyone might have taken offence, follow the above link to the BBC news story and read it.

Or course, I had to see what all the fuss was about and clicked on the link myself in order to read the details. It took no time at all for the following idea to take shape in my mind: this isn’t an issue of Tesco employees with a poor grasp of religious sensibilities in the UK making a goofy gaffe, this is a deliberate conspiracy from within Tesco to grab free publicity by pushing the ‘controversy’ button in the run up to Easter! [Note that we’ve also recently had a media “storm in an egg-cup” involving the Prime Minister, the National Trust and accusations of manufactured controversy.]

A conspiracy built up, and knocked down again

It all seemed so obvious. This is how the conspiracy stacked up in my mind: Someone deep within the Tesco advertising machine had struck upon a fiendishly clever plan. (1) Run a weakly controversial advert in the Holy Week national newspapers where only a minority of the nation will see it. (2) The initial reaction to the ad on social media is picked up by the BBC and other national news agencies, who report it through their own channels. (3) The story goes viral on social media, fueled by parties on both sides of the conventionally religious/secular split making comments like “I’m outraged by Tesco’s insensitivity!” and “Get over yourself, its supposed to be funny!” (4) Issue an official apology, saying that no offense was ever intended (and it wasn’t… it was the public expression of that offense that was intended) (5) Sit back and watch the extra customers pile into Tesco stores to take advantage of the beer and cider offers that they’d seen mentioned on Facebook and Twitter.

Thankfully, after the few seconds that it took me to concoct this conspiracy story I paused to think things through before blurting it out in any public forum. During that pause I could tell that I felt quite pleased with myself for ‘seeing through’ this particular story, that I had taken it a step beyond the knee-jerk reactions of the commentators on social media. Noticing that feeling produced the suspicion that I had fallen for the classic move of fooling myself. I told myself I’d come back to it in the morning, even if it wasn’t such a hot news item then.

This morning, then, I did return to my Good Friday conspiracy. And having let it lie overnight, I felt less possessed by the idea. In fact I outlined my conspiracy privately to a friend, one who I respect deeply for his ability to think critically… although honestly I think I’d chosen to communicate with him because I thought he would agree with me, and be amused at our mutual cleverness and superiority. His point of view was measured, reasonable, and stopped just short of being in total disagreement with me.

My friend made some good points that I’d swept away in my excitement to nail a conspiracy: it is unlikely that Tesco could predict human behaviour that well, so it would be too much of a gamble for them in case it back-fired. And for it to be a corporate strategy it would have to be sustained for a number of instances, without being leaked to the public, and without causing considerable damage to the company’s reputation. Remember Occam’s razor! He also opined that the same people who come up with these conspiracies (which require extraordinary competence from the alleged perpetrators) simultaneously criticise the alleged perpetrators for being incompetent in most other aspects of their business.

Only a fool learns from his own mistakes…

So what have I learned from this (largely inconsequential) affair? With hindsight there shouldn’t be any surprise that it’s the perennial moral of the story: It’s Not All About Me. It seems to be a very very hard lesson for me to learn, and I presume I will never be able to entirely avoid it as it’s something deeply built into the way that we self-aware humans operate.

Firstly, as I’ve already confessed above, there was a sense of self-satisfaction of being clever enough to concoct this conspiracy. In short: aren’t I special? Secondly, I saw myself as being above all the bickering fools reacting to the news story. Again, in short: aren’t I a superior specimen amongst my peers? Thirdly, I saw this as vindication of my pre-existing belief that Tesco was an amoral corporation, willing to deceive the public for their own profit. In short: what I believe is correct, and aren’t I an altogether more ethical entity? In summary, the episode confirms to myself that I’m the super-great guy that I already thought that I was. And this feeling persists, even though day after day I recognise that I was a fool yesterday – but never today!

Critical thinking is crucial

How, then, might all this be connected to the Middle Way? Primarily, I think it is a good illustration of the practice of critical thinking in a low-stakes ethical situation. Consider this quote from Robert M Ellis’s “Migglism: A beginner’s guide to Middle Way Philosophy“:

The development of critical thinking is crucial to the practice of the Middle Way. The Middle Way enables us to address conditions by avoiding the interpretation of our experience through metaphysical preconceptions. Very often those preconceptions become apparent through critical thinking as unjustified assumptions. We need a certain amount of awareness to become aware of a critical problem and apply thought to it, but critical thinking skills are then needed to identify what the unhelpful and unjustified assumptions are.

The major metaphysical preconception in my story is that “I must be right because I feel so right.” It’s a position that’s untenable upon closer inspection, but so often that closer inspection never gets a chance to happen! In this instance it was the fact that I paid attention to the tiny end of the wedge of doubt that my conspiracy story might have no justification whatsoever apart from the fact that it felt so right to me. And notice how I drove the wedge in deeper between the foolishness of my thoughts and the eventual outcome of my actions: I noticed the ‘alarm bells’ that come along with a sense of smug self-satisfaction, I counted to ten (actually, I slept on it), and—perhaps most importantly of all—I offered up the justification for my beliefs to be criticised by an honest friend, one that I could be sure of getting an honest appraisal from, and I was open to the possibility that he may change my mind. And he did.

I can only hope that by practicing and reflecting on this kind of examination of my assumptions in a low-risk situation, that I would be more likely to take a similar approach when the stakes are higher.

My brain’s left hemisphere loves a conspiracy

So, to finish, now that I’ve successfully avoided making a fool of myself on social media with regards to this Good Friday story, I’ve become intrigued as to what might lie behind my desire to concoct a conspiracy. And that’s where apophenia comes in, and I suggest it might be understood in terms of the psychological model of brain lateralisation expounded by Iain McGilchrist. This is how he summarises the nature of the attention of the left hemisphere in the 2016 Blake Lecture:

The attention of the left hemisphere is narrow, targeted, piecemeal, isolative, producing a world of tiny discrete fragments, each appearing certain, static and unchanging. Particles which could, so it seems, be put together like bricks building a wall or cogs making a machine to produce something of use. It has designs on the world.

So, when I read that news story on the BBC website, my left hemisphere analysed it into pieces, compared those pieces with the so-called facts I already knew (which perhaps were really prejudices in the form of absolute concepts such as ‘Tesco is an unethical profit-motivated corporation’) and concocted a satisfying, specific, self-consistent theory that fitted with my pre-existing beliefs. The down-side being that, despite its certainty and logical splendour, it had no degree of objectivity whatsoever. Its assumptions had little justification from wider experience.

Contrast this with the attention of the right hemisphere, as described by McGilchrist:

The right hemisphere meanwhile sees the whole breadth of the picture in a sustained and continuous way. This is an entirely different experiential world, one in which we are involved with, affect and are affected by everything through the sheer fact of our relationship with it. It is indeed a world primarily of relationships, in which the things themselves are never wholly separable from the context in which they lie, and the interconnections which exist between everything that is. It is a world that is never fixed, unchanging, certain, but constantly evolving and creating new wholes.

So, in order to avoid being trapped within the delusions of the left hemisphere, I had to find a way of bringing in the right hemisphere to play its role. Simply appealing to rationality would not work, as that would just be more left-hemisphere action. I had to be sensitive to the ambiguity in the situation, to seek out another person’s point of view, to consider the story in its wider context where that context included my own left-hemisphere’s tendency to prefer simple, certain, rational judgments no matter how inaccurate those judgments are. In other words: apophenia may be appealing, but not justified in the messy muddle and complexity of existence.

Now, I must wrap this up now as all this typing has made me rather thirsty, and I hear that they’ve got some good deals on at my local supermarket…