It’s almost a simplistic metaphor, but … picture three boxes: order, disorder, reorder. … [I]f you read the great myths of the world and the great religions, that’s the normal path of transformation.

–Richard Rohr

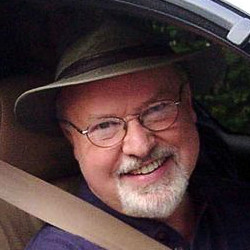

This blog post is the final part of a three-part series inspired by the above quote by Richard Rohr (shown in the photograph on the right). If you’ve not read parts one and two I recommend doing so now so that you appreciate the context of Rohr’s words and how they might apply to the great myths of the world, and to political maturation.

This blog post is the final part of a three-part series inspired by the above quote by Richard Rohr (shown in the photograph on the right). If you’ve not read parts one and two I recommend doing so now so that you appreciate the context of Rohr’s words and how they might apply to the great myths of the world, and to political maturation.

Here I will attempt to frame my own spiritual development in terms of Rohr’s model, although I have some reservations about using the term ‘spiritual’ about myself. I will also acknowledge the limitations of such a simplistic metaphor, with reference to my personal history. I will conclude by taking stock of where I am right now, aged 40 – which is viewed conventionally as the mid-point of life, and where I may perhaps navigate to in future with the aid of the middle way.

Born into disorder? Not me.

What’s difficult is so many people formed in the last 30 years were born into the second box of disorder. [They] don’t have that order to begin with, to reject and improve on.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order.

Due to the specific strictures of our denomination (which was a part of the so-called Holiness movement) I was brought up with very rigid views on the moral validity of abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes, drugs, gambling and pre-marital sex, as well as the more usual protestant insistence on truthfulness before God, honesty in my human interactions, an awareness of my innate sinfulness, observance of the Ten Commandments, belief without evidence (which was termed ‘faith’), worship of the one true God, Bible-reading and prayer. There was also a very strong devotion to charity work, putting others first, observing Sundays as a holy day (so no shopping or engaging in other worldly pursuits on a Sunday) and a lot of encouragement to proselytise to my unconverted peers, through deliberate use of words of personal testimony and through the example (or ‘witness’) of my actions.

This ordered container – which, of course, seemed normal, reasonable and inevitable to me as I grew up, as I didn’t know any different – started to develop holes as I moved into adolescence. It became obvious that other people did not have the same beliefs, and not just those people in the wider ‘sinful’ world but even people who I respected and looked up to within our own congregation. I’m not talking about anything illegal or conventionally controversial like child sex-abuse or misappropriation of funds, but it seemed eye-poppingly amazing to me that other church-goers might be quietly making money on a Sunda or perhaps discreetly but casually conducting a sexual relationship with someone that they weren’t married to. When the holes got big enough, I could get a better view of what might be in store for me in the disorder box. It was a confusing, topsy-turvy place…

For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere.

For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere.

Breaking away

Anyway, the upshot was that by the time I was an adult the cognitive dissonance became too great, in a quiet crisis I abruptly dropped the public pretence of being ‘a good Christian’ in my denomination, to the quiet disappointment and confusion of the older generations in my family. In time my siblings also rejected the same container that they’d been brought up in, but I was the first and with that I had to lead the way. In fact my younger brother rebelled in a more roundabout way when he was 18 by moving to a different continent and becoming even more enthusiastically evangelical… a phase during which we communicated little (he did once urge me, by email, to “repent and get saved”) and which only lasted a couple of years before ending with a rather shameful implosion. He returned and recovered, I’m pleased to say.

The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow this link to a piece I wrote in 1997 about the firewalk we did with Wessex Skeptics). This was easy enough for me to do considering that I was at university studying for a physics degree, with only superficial contact with my family back home. I even adopted a new name through this conversion: James became Jim. Conditioned humility kept me from openly trumpeting my new order to all and sundry, along with some guilt that I’d rejected the certainties of the older generations in my family, who as far as I could tell were good people with the best of intentions in the way that they’d brought me up.

The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow this link to a piece I wrote in 1997 about the firewalk we did with Wessex Skeptics). This was easy enough for me to do considering that I was at university studying for a physics degree, with only superficial contact with my family back home. I even adopted a new name through this conversion: James became Jim. Conditioned humility kept me from openly trumpeting my new order to all and sundry, along with some guilt that I’d rejected the certainties of the older generations in my family, who as far as I could tell were good people with the best of intentions in the way that they’d brought me up.

I adapted quickly to my new sense of order, and very little occurred to challenge it – at first. I was living in a secular society, and my friends and colleagues during my degree, PhD, and teaching career were pretty much all of an atheistic persuasion and those who did have religious beliefs similar to my own from childhood were discreet about it. I knew where I stood, along with the secular majority – viewing organised religion as a childish fantasy based on a human need for consolation – and it hardly had any influence on my life. I winced when I read the polemical work of the more vociferous ‘new atheists’ like Richard Dawkins, who seemed to over-simplify a rather complex situation by attacking crude stereotypes and probably succeeded in pushing moderate Christians away via the ‘backfire effect‘.

Going through disorder

And yet, what I always tell the folks is there’s no nonstop flight from order to reorder. You’ve got to go through the disorder.

So, I think it is more accurate to say that it is only in the past few years, after the certainties of the academic world, after working way too hard as a school teacher for ten years and allowing that ordered container to define my existence, that I have moved into the disorder box. I have been brought to disorder, I have not chosen it. In fact it took a while for me to even realise that I was there, but eventually, gradually, it dawned upon me.

It seems a bit too soon to speak as frankly about this period of my life as I have about the earlier, ordered period, so I’ll just say that in my renewed search for meaning I encountered the Middle Way Society – and I’ve found it to have been immensely helpful in my navigation of the ‘messy middle’ between absolute metaphysical certainties. So, in Richard Rohr’s scheme, I’m right on schedule – as I enter mid-life I’m bumbling around in the disorder box, but I think there’s hope that I can bumble less and eventually crawl through into the metaphorical reorder box.

There is, as always, a danger of absolutising this model and treating it as a single linear progression through three distinct stages, with a definite ‘destination’. Rohr’s usage of it is as an over-arching framing of spiritual development during a person’s life, from naive, exclusive ‘early stage’ religion through to a more mature, inclusive, flexible religion that unites rather than divides. In the shorter term our integration is likely to proceed in a series of cycles rather than through a single pass through the sequence order-disorder-reorder. Also our integration may well proceed asymmetrically, which is not wholly a bad thing as explained in this video from the Middle Way philosophy series.

I’m still uncomfortable with the specific term ‘spiritual’, as I (rather clumsily) tried to explain in the podcast interview with Barry last year: to me the term is inextricably associated with New Age ‘woo’, eternal souls and Cartesian dualism, the Pentecostalist understanding on the ‘Holy Spirit’, and other metaphysical absolutes which cannot be justified by experience. Richard Rohr, as you might expect, seems to be quite comfortable with using the term but I’m encouraged by the fact that he’s more inclined to talk about spiritual development as the increasingly ethical use of your intellect, heart and body, which seems a long way from metaphysical woo.

A term that’s more agreeable to me than ‘spiritual development’ is ‘integration’, as used here in the Middle Way Society. What others may look upon as my spiritual development, I would like to name as my progress with integrating desire, meaning and belief – and in the process becoming more ethical, a person of greater integrity. As a child I could see a disconnect between the stated beliefs of the adults around me, and their ethical actions. The archaic collection of metaphysical claims which formed their creed were ostensibly used to justify their actions, but I thought that their actions would probably have been just as ethical in the absence of these words. Perhaps a more succinct way of putting it is that there was great emphasis on orthodoxy, and an equally strong emphasis on orthopraxy, but that the connection between the two was not necessarily what it was claimed to be.

A term that’s more agreeable to me than ‘spiritual development’ is ‘integration’, as used here in the Middle Way Society. What others may look upon as my spiritual development, I would like to name as my progress with integrating desire, meaning and belief – and in the process becoming more ethical, a person of greater integrity. As a child I could see a disconnect between the stated beliefs of the adults around me, and their ethical actions. The archaic collection of metaphysical claims which formed their creed were ostensibly used to justify their actions, but I thought that their actions would probably have been just as ethical in the absence of these words. Perhaps a more succinct way of putting it is that there was great emphasis on orthodoxy, and an equally strong emphasis on orthopraxy, but that the connection between the two was not necessarily what it was claimed to be.

An ongoing process of transformation

I’m not claiming to have achieved perfect wisdom, in fact I don’t really believe that such as thing is anything other than an archetypal aspiration anyway. To be more objective in the justification of my beliefs, to hold them provisionally and adapt them incrementally is a more realistic and ethical proposition. In the past few years I think I’ve had a few tastes of what might lie ahead in the second half of my life, beyond the current disorder.

For example, although I’ve felt guilty about leaving the religion that I was brought up in, I can now appreciate that I rejected the ideology and the beliefs of my parents and grandparents, without rejecting the parents and grandparents themselves. In Christianity this sentiment was expressed by Saint Augustine as “hate the sin, but love the sinner”, but – as Gandhi pointed out – this is easy enough to understand though rarely practiced.

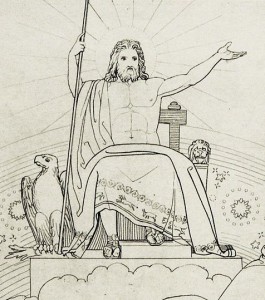

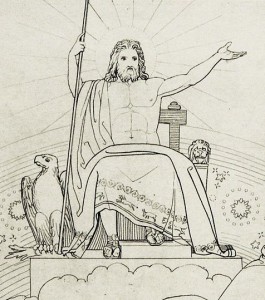

I can also see that the Zeus-like Christian God that I was brought up with is a rather childish (but widespread) interpretation of Christian theology, and my subsequent rejection of all understanding of an Abrahamic God was also rather extreme – more subtle and nuanced agnostic understandings of the concept of “God” exist, and the meaning associated with the God archetype does not have to be thrown out with the metaphysical bathwater. For example, what I came to see as the preposterous proposition of Jesus’s resurrection at Easter can in fact be a source of meaning and inspiration, as discussed in this superb article by Robert M. Ellis.

I can also see that the Zeus-like Christian God that I was brought up with is a rather childish (but widespread) interpretation of Christian theology, and my subsequent rejection of all understanding of an Abrahamic God was also rather extreme – more subtle and nuanced agnostic understandings of the concept of “God” exist, and the meaning associated with the God archetype does not have to be thrown out with the metaphysical bathwater. For example, what I came to see as the preposterous proposition of Jesus’s resurrection at Easter can in fact be a source of meaning and inspiration, as discussed in this superb article by Robert M. Ellis.

Thirdly, with regards to the way that I choose to live my life, I can still abstain from smoking, from getting into debt and from lying… but that it is largely my choice, what currently seems most appropriate within the wider conditions of my life, and not a set of imperatives dictated to me by the absolute metaphysical dogma of a particular religious tradition. My upbringing could be (somewhat uncharitably) viewed as an indoctrination into a specific moral code, but in rejecting the supposed authority behind this code I do not instead have to embrace a nihilistic relativism. To paraphrase from Robert’s books on Middle Way philosophy:

The absolutist’s mistake is to understand the right choice in terms of overall principles regardless of the specifics of the situation. The relativist’s mistake is to believe that there is no right choice.

In conclusion…

Turning 40 is something I’ve mentioned to my friends and associates, not because it has great significance for me, but more because it seems to have significance for them. In opposition to our youth-obsessed culture’s conventional position on ageing, I approve of getting older: looking back I can see that I’m not the same fool I was at 30 (or 20, or 10, or even 39 and 51 weeks). Here’s to maturation in general, not just spiritually, and here’s (hopefully) to the next 40 years!

Featured image is an engraving by William Blake, from The Pilgrim’s Progress, via Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Richard Rohr by Svobodat [License: CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Image of ‘God on this throne’ is actually an engraving of Zeus from John Flaxman’s Iliad, via Wikimedia Commons

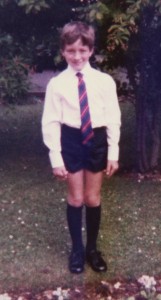

The three photos of me (aged roughly 7, 18 and 23) were scanned in from the original prints. Retro.

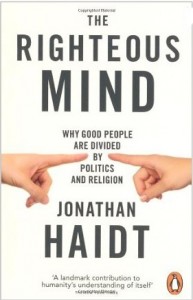

One of the most prominent researchers in this area is Jonathan Haidt, and in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind he sums it up like this:

One of the most prominent researchers in this area is Jonathan Haidt, and in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind he sums it up like this: In the subtitle above I imply that I possess the metaphorical elephant, whereas – in the light of Haidt’s moral psychology model – it might be more accurate to say that the elephant both is me (as the part of my mind that works before and at a more fundamental level than my conscious cognition) and has me (in the sense that the conscious cognitive “I” serves it and has little control over where the elephant is going).

In the subtitle above I imply that I possess the metaphorical elephant, whereas – in the light of Haidt’s moral psychology model – it might be more accurate to say that the elephant both is me (as the part of my mind that works before and at a more fundamental level than my conscious cognition) and has me (in the sense that the conscious cognitive “I” serves it and has little control over where the elephant is going). Looking back on it, perhaps there was a bit of embarrassment that I didn’t have a rational reason for not wanting to eat eggs any more, after all, usually people want to know why you’ve changed your position on an issue and it seems culturally appropriate to have a ‘proper’ rational reason. My wife said something like “If that’s your decision that I stand by you making it.” and I went off to make something eggless for our evening meal. The elephant had decided: “Boom! No more eggs for you!” and then my cognitive mind was left floundering around trying to do some strategic reasoning that would no doubt be required in socially justifying my new food ethos.

Looking back on it, perhaps there was a bit of embarrassment that I didn’t have a rational reason for not wanting to eat eggs any more, after all, usually people want to know why you’ve changed your position on an issue and it seems culturally appropriate to have a ‘proper’ rational reason. My wife said something like “If that’s your decision that I stand by you making it.” and I went off to make something eggless for our evening meal. The elephant had decided: “Boom! No more eggs for you!” and then my cognitive mind was left floundering around trying to do some strategic reasoning that would no doubt be required in socially justifying my new food ethos. It goes back, of course, to childhood. I was a fantastically fussy eater, ‘difficult’ about food, and I cannot remember ever not being this way. My brother, two years younger, was quite different: a human dustbin, he’d happily eat what I would not, and probably this was why so many adults asked if we were twins; despite him being two years younger he was always the same size as me (as you can see in the photo on the right, taken perhaps when I was 9 and he was 7).

It goes back, of course, to childhood. I was a fantastically fussy eater, ‘difficult’ about food, and I cannot remember ever not being this way. My brother, two years younger, was quite different: a human dustbin, he’d happily eat what I would not, and probably this was why so many adults asked if we were twins; despite him being two years younger he was always the same size as me (as you can see in the photo on the right, taken perhaps when I was 9 and he was 7). What was the ‘right’ choice for us to make? To what extent would he decide what he ate and why? Either the elephant, or pragmatism, made the decision: we weren’t going to specially buy in meat for him to eat at home. He grew up healthy and un-deformed, despite some frowning from meat-eating adults, and he eventually settled into something like a pescatarian diet—vegetarian, but with occasional fish dishes—and, as far as I know, he’s never eaten the conventional chicken, beef, turkey, lamb and pork foods that most of his friends eat.

What was the ‘right’ choice for us to make? To what extent would he decide what he ate and why? Either the elephant, or pragmatism, made the decision: we weren’t going to specially buy in meat for him to eat at home. He grew up healthy and un-deformed, despite some frowning from meat-eating adults, and he eventually settled into something like a pescatarian diet—vegetarian, but with occasional fish dishes—and, as far as I know, he’s never eaten the conventional chicken, beef, turkey, lamb and pork foods that most of his friends eat.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order. For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere.

For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere. The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow

The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow