[In recent months I have written very little by way of blogs on this site, due to being preoccupied with other matters – and, when I had the time, finding that I still lacked the creative momentum. However, I have already written large amounts of material on the Middle Way, particularly in the form of my books, and I have decided to start offering some selected extracts from my books as taster blogs. They will just be lightly edited to fit the blog form. This one comes from the beginning of Middle Way Philosophy 3: the Integration of Meaning. – Robert]

Although meaning has traditionally been separated into the two spheres of cognitive and emotional, Middle Way Philosophy involves an inclusive and unifying account of these two spheres of meaning. In every practical situation in which a flesh-and-blood person finds a given symbol meaningful, there must be both cognitive and emotional aspects to that meaning.

By “cognitive” meaning, I mean the recognition of symbols, particularly but not only words, in terms of semantic equivalences: for example, dictionary definitions. The bare recognition that a cross represents Christianity is cognitive. The understanding that the word “cross” refers to the shape of two rectangles overlapping in their centres, with the longer sides of each at 90° to the other, is also cognitive. The ability to recognise a cross and pick it out from other shapes tests understanding of its cognitive meaning.

Cognitive meaning (when treated in isolation in its own limited terms of reference) ultimately depends on the truth conditions of propositions (i.e. the conditions in which a statement would be true), even when it is applied to the meaning of a non-verbal symbol. That is because my ability to cognitively identify a cross depends on my ability to judge whether a statement like “This is a cross” or “This is not a cross” is “true” or “false” in terms I would accept in my representation of the world. “Cross” by itself doesn’t tell me what that judgement would be, because it doesn’t tell me whether a cross is being claimed to be present at all, or where it is. The dictionary definition of a cross can only follow from this ability to tell what is a cross and what is not in the terms in which we accept the word. This is the standard account given in the theory of meaning used by analytic philosophers, which applies exclusively to cognitive meaning.

This cognitive meaning also applies to the merely cognitive interpretation of non-verbal symbols, or what have often been called “signs”. A “sign” in this sense is just a non-verbal indicator of a verbal equivalent: a cross means “Christianity”; a red traffic light means “stop”. Because our understanding of these signs depends on our ability to relate them to verbal equivalents, and those verbal equivalents depend for their meaning on truth-conditions, the cognitive meaning of a sign also depends on truth-conditions. The same can be said for signs in a wider sense. If I think the unpleasant noise of a violin is a sign that it is badly tuned, or a footprint is a sign of deer, then these meanings depend similarly on my ability to relate the sign I am experiencing to a verbal equivalent, and ultimately to recognise whether propositions like “The violin is badly tuned” or “Deer have been here” are “true” or “false” in terms I would accept.

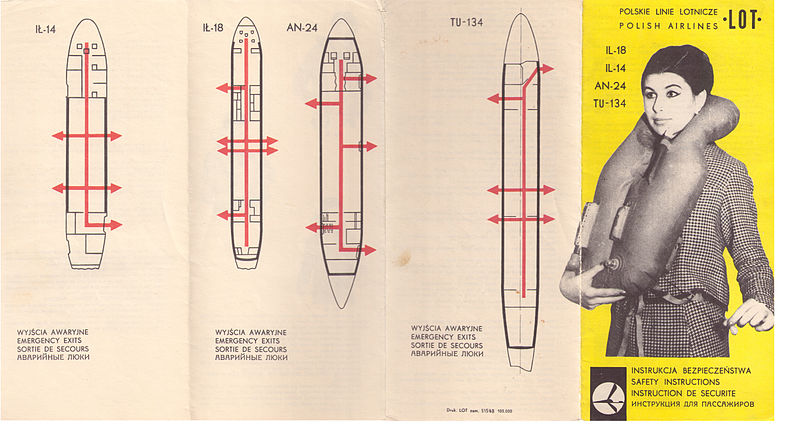

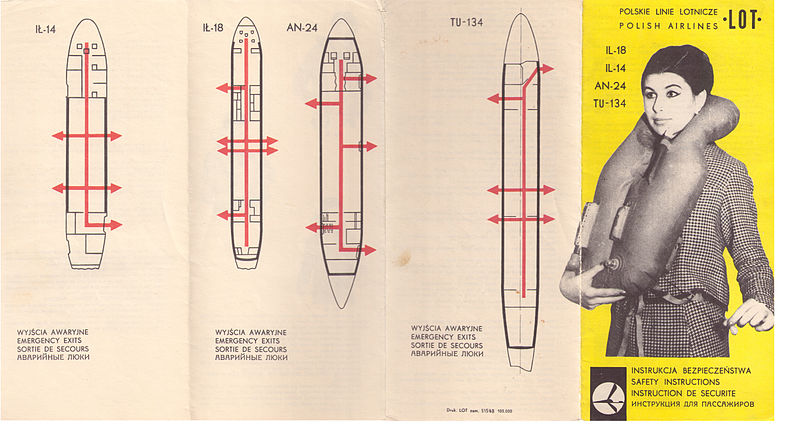

By “emotional” meaning, on the other hand, I mean our responses to symbols: responses that vary in intensity. Regardless of my appreciation of its cognitive meaning, a given statement may be of enormous interest to me, or of practically none. If I am waiting expectantly for an announcement that is crucially important to the fulfilment of my desires: say, the announcement of whether or not I get a job I’ve been interviewed for, or an indication of whether a sexual interest is reciprocated, the language that follows is highly meaningful. On the other hand, routine and formalistic language is likely to be of very little interest, because we know that the person giving it is only going through the motions: for example, the safety information at the beginning of a flight (unless it’s your first flight), or the legal terms and conditions that most people don’t read before installing new software. I can fully understand such language in a cognitive sense, and yet barely register it, because it has little emotional meaning for me.

Emotional meaning is not ultimately dependent on interpretation in terms of propositions, or indeed on interpretation of any kind. It means what it means because of its impact on us, regardless of whether it is a misunderstanding of what the speaker or writer meant to communicate. Emotional meaning can be attached to single decontextualised words (think of “vomit” or “blood”) and to symbols, or to anything that we choose to interpret as meaningful. The emotional meaning of a cross as a symbol may depend on our background and relationship to Christianity, and may be very negative or very positive. Our emotional relationship to a favourite tree on a frequent walk, or a certain gurgle made by a baby, is also a matter of emotional meaning, despite the fact that the symbol to which we attach this significance may be purely personal and not recognised by others as symbolic.

My central thesis about the relationship between these two spheres of meaning is that neither is ever wholly absent. Although our experience of certain symbols may be overwhelmingly dominated by one, and the other may be very attenuated, we can never justifiably claim of any symbol that it has no cognitive or no emotional significance whatsoever. This is because, in the concrete situation in which people experience meaning, both are required to some degree.

This is perhaps most obvious in the case of language that depends strongly on its cognitive meaning, where its emotional meaning may be attenuated. A bored school-child, who is supposed to be reading a textbook which she is quite capable of understanding but has no interest in, will find that textbook as meaningless as any set of undeciphered hieroglyphs. Attention is simply a necessary condition for meaning, and attention has to be motivated by desire. In the absence of such desire, that meaning is absent. As soon as some attention is brought to bear on the symbols, though, cognitive meaning can also follow.

I set aside here the abstracted scenario assumed by analytic philosophers, who assume that a proposition can have meaning by itself, even if it is not a meaning for anyone. Analytic writings on meaning are full of examples like “Paris is the capital of France if and only if Paris is the capital of France”. This is the locus classicus of analytic philosophy abstracting itself into irrelevance by totally disregarding all the conditions in experience by which people find “Paris is the capital of France” to be meaningful. People find it meaningful because they have an understanding of the terms, yes, but also because they find the claim worthy of attention.

Where symbols depend much more strongly on emotional meaning, however, there also needs to be some element of cognitive significance present, however attenuated. Take the example mentioned earlier of a favourite tree. That tree is meaningful to me because I frequently pass it and admire it. I do not merely perceive it, but also accord it a specific significance. So although the significance of the tree consists mainly on my admiration of it, it also has a cognitive significance that could be given a verbal equivalent, such as “That’s one of my favourite trees.”

There is obviously a vague boundary line between perception and meaning, particularly as perception is not a uniform appraisal of everything in view, but is already guided by what might be taken to be at least a potential form of meaning. The boundary-line could be roughly defined by desire, because I define meaning in general as a habitual attachment of desire to a symbol. If I have no particular desires in relation to a landscape, say, I may perceive that landscape without attaching any particular meaning to any features of it. However, if I pick out an ash tree because I want to impress my companion with my tree-identification skills, or because its shape has an aesthetic appeal to me, the intercession of desire has simultaneously created a symbol. Where there is a symbol, there is meaning rather than merely perception.

This raises the question of how far the capacity for meaning of this kind is a unique capacity of persons: “persons” generally meaning, in practice, human beings with sufficient sentience, although theoretically extending to other possible persons such as intelligent aliens. There seems to be no good reason to limit meaning to persons, because other animals seem capable of experiencing both the emotional and the cognitive aspects of meaning. Obviously particular objects have an emotional impact on animals: for example, a dog may signal its desire for a walk by bringing its lead that it associates with walks. However, this same example has a cognitive element because the lead, for the dog, is obviously a sign for “walk” and could be given a verbal equivalent. The verbal equivalent does not have to be given by the dog for it to have that significance for the dog. The cognitive meaning of “I want to go for a walk” as the meaning of the dog’s gesture of bringing the lead ultimately depends on its truth conditions, but not on the dog being able to analyse the truth conditions, any more than it does for the majority of human beings, who would also (if they have not studied any philosophy) probably not be able to analyse the meaning of their language in terms of truth conditions. Meaning, even when understood representationally (i.e. as purely cognitive), thus provides us with no discontinuous justification for discrimination against animals purely on grounds of species. Animals may have a less sophisticated understanding of meaning, but their relationship to meaning only varies incrementally from ours.

The analysis of meaning in terms of cognitive and emotional spheres is of limited value. I think a Lakoffian account of meaning in terms of bodily experience and metaphorical extension is generally more helpful. However, I do not regard the Lakoffian account as inconsistent with cognitive and emotional accounts of meaning, provided that they are understood in the inclusive way I have described here. What Lakoff and Johnson effectively do is to explain why symbols have an emotional (or, more accurately, a bodily) impact on us. Their work on metaphorical extension also helps to explain how the cognitive element of meaning can be related to bodily meaning without appealing to “truth” or “falsity” of an abstract or metaphysically defined sort. However, I have started by relating these two spheres of meaning in order to create some continuity between my account of meaning and those widely used, and to show that my account does not contradict them so much as put them into a wider context.

“Representationalism” is not simply a representational or truth-dependent account of meaning, but the belief (or assumption) that such an account is an exhaustive one, or that meaning is entirely cognitive. Similarly, its less common opposite “expressivism” is not just the belief that meaning is emotional, but the belief that it is entirely emotional and has no cognitive element. The Middle Way can be applied here to avoid such metaphysical accounts of meaning, which are absolute, dualising, and non-incremental. However, like many other metaphysical beliefs, representationalism and expressivism are based on the recognition of certain conditions, the interpretation of which has been over-extended and absolutised. We can reject both representationalism and expressivism, whilst simultaneously accepting that language and other symbols both represent and express. Provided that we maintain an awareness of both, these explanations can both be incorporated into a wider account of meaning.

Pictures:

- Cross in the Sky by Photo Dharma (CCA 2.0)

- LOT safety card from 1968