If we are told about Santa Claus, will we “automatically” believe in Santa Claus?

I’ve recently been reading a big tome – ‘Belief’ by professor of psychology James E. Alcock. In many ways this book can be recommended as a helpful and readable summary of a great deal of varied psychological evidence about belief, including all the ways that beliefs based on perception and memory are unreliable, and all the biases that can interfere with the justifiability of our beliefs. However, I’m also finding it a bit scientistic, particularly in its reliance on crude dichotomies between ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’ beliefs, for instance. It seems like a good indicator of the mainstream of academic psychological opinion, with both its strengths and its limitations. (I haven’t got to the end of the book yet, so all of those judgements will have to remain fairly provisional.)

One particular point has interested me, that for some reason I had not come across before. This is Alcock’s claim that accepting what we are told as ‘truth’ is “the brain’s default bias”.

There is abundant and converging evidence from different research domains that we automatically believe new information before we assess it in terms of its credibility or assess its consistency with beliefs we already hold. Acceptance is the brain’s default bias, an immediate and automatic reaction that occurs before we have any time to think about it. Only at the second stage is truth evaluated, resulting in confirmation or rejection. (p.152)

One of Alcock’s examples of this (seasonally enough) is the child’s belief in Santa Claus. If people tell the child that Santa Claus exists, he or she will ‘automatically’ believe exactly that. Now, it’s one thing to claim that this is quite likely, but quite another to claim that it is ‘automatic’.

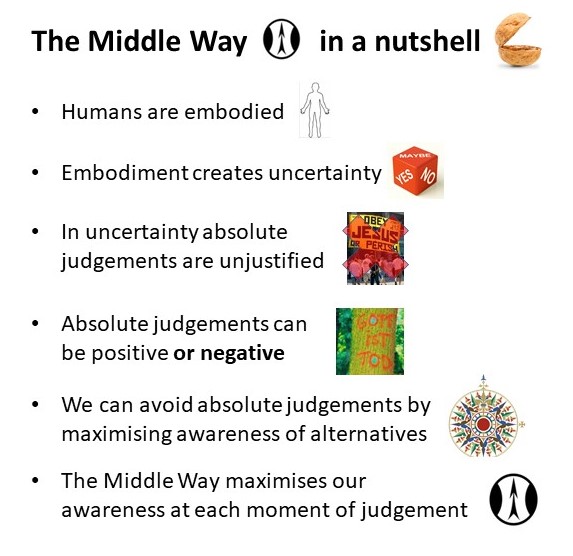

If this is correct, it seems to be a significant challenge to the things I have been writing and saying in the last few years in the context of Middle Way Philosophy. If we automatically believe what we are told, then it seems that there is no scope for provisionality in the way we initially believe it, and we are left only with ‘reason’ – i.e. a second-phase reflection on what we’ve come to believe – to rescue us from delusion. The distinction that I like to stress between meaning and belief would also be under threat, because we could not merely encounter meaningful ideas about possible situations without immediately believing them. So, I was sceptical when I encountered this information. But, it coming from a professor of psychology, I certainly needed to look into it and check my own confirmation biases before rejecting it. Was this claim actually well evidenced, or had dubious assumptions been made in the interpretation of that evidence?

Alcock references a 2007 review paper that he wrote in collaboration with Ricki Ladowsky-Brooks: “Semantic-episodic interactions in the neuropsychology of disbelief”. This paper does summarise a wide range of evidence from different sources, but reading it easily made it apparent that this evidence has also been interpreted in terms of assumptions that are highly questionable. The most important dubious assumption involves the imposition of a false dichotomy: namely that the only options in our initial ‘acceptance’ of a meaningful idea about how things might be are acceptance of it as ‘truth’ or rejection of it as ‘falsehood’. If one instead approaches this whole issue with an attempt to think incrementally, then we can understand our potential responses in terms of a spectrum of degrees of acceptance – running from certainty of ‘truth’ or ‘falsehood’ at each extreme, via provisional beliefs tending either way, to an agnostic suspension of judgement in the middle. The introduction to Alcock and Ladowsky-Brooks’ paper makes it clear that this dichotomy is being imposed when it says that

The term ‘‘belief’’ will refer to information that has been accepted as ‘‘true’’, regardless of its external validity or the level of conviction with which it is endorsed.

If we start off by assuming that all degrees of conviction are to be categorised as an acceptance of “truth”, then we will doubtless discover exactly what our categorisations have dictated – that we accept things as ‘true’ as a default. This will be done in a way that rules out the very possibility of separating meaning from belief from the start. But since the separation of meaning from belief enables us to approach issues like religion and the status of artistic symbols in a far more helpful way, surely we need to at least try out other kinds of assumptions when we judge these issues? Alcock’s use of “true” as a supposed default in the “truth effect” that he claims is so broad that it effectively includes merely finding a claim meaningful, or merely considering it. This seems to involve an unnecessary privileging of the left hemisphere’s dichotomising operations over the more open contributions of the right, when both are involved in virtually every mental action.

The alleged two-stage process that then allows us to reconsider our initial assumption that a presented belief is ‘true’, and decide instead that it is ‘false’, also turns out not to necessarily consist of two distinct stages. On some occasions, we do immediately assume that a statement is false, because it conflicts so much with our other beliefs. However, Alcock identifies “additional encoding” in the brain when this is occurring, implying that both the stages are taking place simultaneously. Yet if both stages can take place simultaneously, with the second nullifying the effects of the first, how can the first stage be judged “automatic”?

So, in some ways Alcock obviously has a good point to make. Very often we do jump to conclusions by immediately turning the information presented to us into a ‘truth’, and very often it then requires further effortful thinking to reconsider that ‘default’ truth setting. But the assumptions with which he has interpreted his research have also unnecessarily cut off the possibility of change, not just through ‘reason’, but through the habitual ways in which we interpret our experience. There is no discussion of the possibility of weakening this ‘truth effect’ – yet it is fairly obvious that it is much stronger in some people at some times than others at other times. He seems not even to have considered the possibility that sometimes, perhaps with the help of training, our responses may be agnostic or provisional, whether this is achieved through the actual transformation of our initial assumptions, or through the development of wider awareness made so habitual that the two phases he identifies are no longer distinct.

This issue might not be of so much concern if it did not seem to be so often linked to negative absolutes being imposed on rich archetypal symbols that we need to appreciate in their own right. If I consult my own childhood memories of Santa Claus talk, I really can’t identify a time when I “believed” in Santa Claus. However, that may be due to defective memory, and it may well be the case that many young children do “believe” in Santa Claus, as opposed to merely appreciating the meaning of Santa Claus as a symbol of jollity and generosity. At any rate, though, surely we need to acknowledge our own culpability if we influence children to be obsessed with what they “believe”, and accept that it might be possible to help them be agnostic about the “existence” of Santa Claus? To do this, of course, we need to start by rethinking the whole way in which we approach the issue. “Belief” is simply not relevant to the appreciation of Santa Claus. It’s quite possible, for instance, for children to recognise that gifts come from their parents at the same time as that Santa Claus is a potent symbol for the spirit in which those gifts are given. We don’t have to impose that dichotomy by going straight from Santa Claus being “true” to him being “false”, when children may not have even conceived things in that way before you started applying this as a frame. If we get into more helpful habits as children, perhaps it may become less of a big deal to treat God or other major religious symbols in the same way.

Apart from finding that even professors of psychology can make highly dubious assumptions, though, I also found some interesting evidence in Alcock’s paper for that positive possibility of separating meaning from belief. Alcock rightly stresses the importance of memory for the formation of our beliefs: everything we judge is basically dependent on our memory of the past, even if it is only the very recent past. However, memory is of two kinds that can be generally distinguished: semantic and episodic. Those with brain damage may have one kind of memory affected but not the other, for instance forgetting their identity and past experience but still being able to speak. Semantic memory, broadly speaking, is memory of meaning, but episodic memory is memory of events.

Part of what looks like a big problem in the assumptions that both philosophers and psychologists have often made is that they talk about “truth” judgements in relation to both these types of memory. Some of the studies drawn on by Alcock involve assertions of “truth” that are entirely semantic – i.e. concerned with the a priori definition of a word, such as “a monishna is a star”. This is all associated with the long rationalist tradition in philosophy, in which it is assumed that there can be such things as ‘truths’ by definition. However, this whole tradition seems to have a mistaken view of how language is meaningful to us (it depends on associations with our bodily experience and metaphorical extensions of those associations), and to be especially confused in the way it attributes ‘truth’ to conventions or stipulations of meaning used in communication. No, our judgements of ‘truth’, even if agnostic or provisional, cannot be semantic, but need to rely on our episodic memory, and thus be related to events in some way. If we make this distinction clearly and decisively enough (and it goes back to Hume) it can save us all sorts of trouble, as well as helping us make much better sense of religion. Meaning can be semantic and conventional, whilst belief needs to be justified through episodic memory.

Of course, this line of enquiry is by no means over. Yes, I do dare to question the conclusions of a professor of psychology when his thinking seems to depend on questionable philosophical assumptions. But I can only do so on the basis of a provisional grasp of the evidence he presents. I’d be very interested if anyone can point me to any further evidence that might make a difference to the question of the “truth effect”. For the moment, though, I remain highly dubious about it. We may often jump to conclusions, but there is nothing “automatic” about our doing so. Meanwhile, Santa Claus can still fly his sleigh to and from the North Pole, archetypally bestowing endless presents on improbable numbers of children, regardless.

Santa pictures from Wikimedia Commons, by Shawn Lea and Jacob Windham respectively (both CCBY2.0)