At the time I was writing ‘The Buddha’s Middle Way’ (published this year), in 2017, I was able to refer to Stephen Batchelor’s 2015 book ‘After Buddhism’ as its nearest forerunner, but I had not yet read Batchelor’s collection of essays ‘Secular Buddhism’, which was only published in 2017. Reading that further book, more recently, I don’t think it would have made a huge difference to any of the (largely positive) things I said about Batchelor’s work. However, its essay ‘A Secular Buddhism’ does seem to be the nearest thing to a manifesto Batchelor has produced, and I guess that it’s one of the most influential statements to date of what ‘secular Buddhism’ means. For that reason, if no other, I feel it’s worth engaging with and responding to.

The reason I’ve been increasingly interested in Batchelor’s work, and have also been very glad to meet him personally, is not because I identify myself with the label ‘secular Buddhist’ (though I have been through an earlier phase when I used the term). However, I continue to be interested in what lies behind it – namely a fruitful process of deep critical thinking about Buddhist tradition, parallel to the similar process that is going on in relation to many other traditions.

Batchelor’s other metaphor for what he means by ‘Secular Buddhism’, ‘Buddhism 2.0’ appeals to me a little more. Despite its IT connotations, and the danger that these connotations will be taken too literally or reductively, it does convey the key idea of changing the paradigm that creates key assumptions about Buddhist practice. To do ‘Buddhism 2.0’ you don’t have to change your “hardware” (i.e. your body and brain) nor your specific app (e.g. ethical or meditation practice), but you do need to change the “operating system” that gives a wider formatting to your practice. You need to do so because the old operating system is no longer well-adapted to a new set of conditions. That’s a metaphor that could just as easily be applied to the reform of other traditions: e.g. Christianity 2.0, Science 2.0, or Liberalism 2.0.

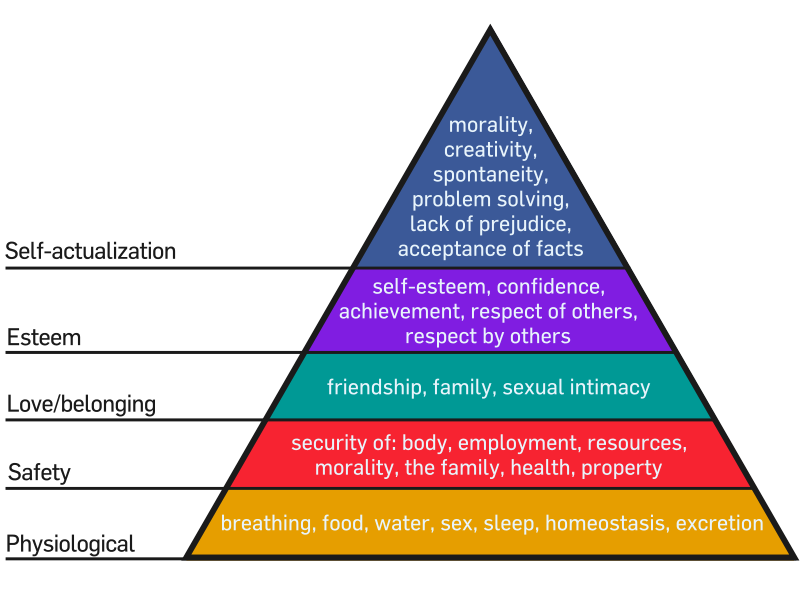

The switch from one operating system to another may also seem like a sudden one, because it involves a disengagement from one set of connected assumptions in order to re-engage with another. Batchelor captures this very well when he writes about a “gestalt switch” from a metaphysical interpretation of Buddhist doctrines to a pragmatic one. In the work of Robert Kegan on levels of adult psychological development, that switch can be seen as the one between level 4 (thinking based on paradigmatic rational rules) to level 5 (flexibly moving between paradigms with a practical justification).

When this switch occurs, how does the new ‘operating system’ differ from the old one? Here, the key point where I agree with Batchelor wholeheartedly is that the new operating system is pragmatic whilst the old is dogmatic. The question, however, is what exactly “pragmatic” means. The implications of pragmatism need to be simultaneously pursued both in theory and in practise if they are to provide a strong enough alternative to the dogmas people are used to relying on. The more long-term and universal one tries to make one’s pragmatism, the further one will need to look beyond one’s personal experience and one’s immediate audience, and thus the wider and more fruitful one’s pragmatism is likely to become. Batchelor’s strength is that of communicating new possible approaches to people who are interested in Buddhism in a way that can inspire them and is consistent with practical experience. However, his limitations lie more in the area of how much he critically examines the perspectives he offers, to make his pragmatism more universal.

This takes me to my concerns about the framing of ‘Buddhism 2.0’ as ‘Secular Buddhism’. In his essay ‘Secular Buddhism’, Batchelor starts off by trying to clarify exactly what he means by that term. Let’s start with ‘Secular’. Batchelor says that there are three senses of secularity he is using: (1) opposition to religion, (2) being concerned with this world, and (3) involving a transfer of authority from ‘church’ to ‘state’. If that is what ‘secular’ means, then identifying my approach with any of them would worry me, because they all seem to rely on a (thoroughly false, in my view) dichotomy between ‘secularity’ and ‘religion’. If we state that we are concerned with this world, that seems to imply that we are still avoiding concern with another one, and if we are transferring authority away from religious institutions, this also suggests that we are rejecting religious institutions as holders of power. Surely that is continuing with the old paradigm, but just flipping our priorities within that paradigm, rather than adopting a new one? To adopt a new pragmatic paradigm, surely we need to apply the same sorts of autonomous criteria to critique both ‘religious’ and ‘non-religious’ spheres, recognising that religion is a complex system embedded in human societies?

There are, indeed, other possible uses of the term ‘secularism’, that I think may get a bit closer to what I take Batchelor to mean. Charles Taylor, in his big book ‘A Secular Age’ offers another alternative sense of secularity, as a transition “from a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others”. The phenomenon of secular thinking has given us options that were not there before: to follow the church, to think oppositely to the church, and potentially, also, to break the dichotomous paradigm on which the popular view of religion as absolute belief depends. That’s a type of secularism I would personally find it much easier to sign up to: both individually and socio-politically, I think it’s very important to maintain those options. But secularists would need to be a great deal clearer about this as the prime reason for secularism than they tend to be for me to sign on the dotted line. Batchelor’s account of it does not suggest that it’s this kind of definition that he has in mind.

The other side of Batchelor’s account of ‘Secular Buddhism’ is the ‘Buddhist’ part. Here it may be helpful to quote him at some length.

On what grounds would such a Buddhism 2.0 be able to claim that it is “Buddhism” rather than something else altogether? Clearly, it would need to be founded on canonical source texts, be able to offer a convincing interpretation of key practices, doctrines, and ethical precepts, and to provide a sufficiently rich and integrated theoretical model of the dharma to serve as the basis for a flourishing human existence. (p.80)

Firstly, here, I wonder why he is so concerned as to whether ‘Secular Buddhism’ could possibly be mistaken for “something else altogether”. It’s a worry I’ve also encountered amongst many other Buddhists when discussing these issues, to such an extent that when I asked one Buddhist scholar why he was so narrowly focused on the Buddhist tradition, he answered “because I’m a Buddhist” – as though that answered the question! It should hardly be necessary to point out to Buddhists that essentialism is not part of their brief. Surely, if the practices work, it matters not in the least whether they are thought of as ‘Buddhism’? What matters practically, in relation to the Buddhist tradition, is whether it is a source of inspiration and practical support for spiritual progress, not what we call it. Its practical function as a tradition does depend on continuity, but not on essentiality, and helpful continuity can be maintained without essential identity.

Charitably assuming, then, that what Batchelor wants here more deeply is an effective practical relationship to Buddhist tradition rather than ultimate grounds for claiming that it is not ‘something else’, we can then find three criteria for it in the quotation above, only two of which are obviously pragmatic. A convincing interpretation of all the elements of the tradition is undoubtedly needed to maintain helpful continuity with it, and “a sufficiently rich and integrated model of it” to be practically helpful is also a pragmatic criterion. Why ever, though, does it need to be “founded on canonical source texts”?

There seems to be a contradiction between this criterion and Batchelor’s approach on the very next page:

The more I am seduced by the force of my own arguments, the more I am tempted to imagine that my secular version of Buddhism is what the Buddha originally taught, which the traditional schools have either lost sight of or distorted. This would be a mistake, or it is impossible to read the historical Buddha’s mind in order to know what he “really” meant or intended. (p.81)

Why does secular Buddhism need to be “founded on canonical source texts” if these very source texts have such a highly debatable relationship to the Buddha? Even if the scholarly lines of transmission were clearer than they are, would there not also be a basic issue of responsibility here? If we have responsibility for our practice, surely we cannot take any “canonical source text” as a complete account of it? Once we take responsibility for an idea, its source becomes irrelevant.

However, responsibility needs to be exercised in interpreting Batchelor as well as in interpreting scriptures. I’m fairly sure, having met him and discussed some of these issues, that he would deny that he intended “canonical source texts” to be an absolute source of authority. Nevertheless, I think there is a major issue about what one implies when one argues about such texts. In my own book ‘The Buddha’s Middle Way’, I have tried to make it extremely clear that I am using source texts from the Pali Canon as a source of inspiration rather than as a source of ‘truth’. Even then I found that some early readers of my draft book did not understand this approach, assuming that any reference to the texts was effectively an appeal to authority, and any changed interpretation must be based on a rival historical or textual claim of some kind. Appealing to authority is such an engrained habit in every sphere of religion, that one has to make a supreme effort even to open the Overton Window to other possibilities. People will still read in what they are used to even when you try to make it very explicit. In the absence of an extremely explicit statement about how one is using texts, then, I think it is very difficult to avoid the presumption, in readers if not in the writer, that one is offering a new version of what the Buddha “really” meant. For that reason I would like Batchelor to be very much more explicit on this point.

I think Batchelor’s concern with the dating and origin of texts also leaves him open to this interpretation. Sometimes the fact that one text is earlier or later than another is an informative part of the total story it offers and its significance. For example, knowing that ‘The Tempest’ is a late play of Shakespeare’s does make a difference to our appreciation of it, as we can understand the echoes of Shakespeare himself in the character of Prospero. In a similar way, awareness that the ‘Chapter of Eights’ in the Sutta Nipata is probably a very early text may help us to interpret it contextually. However, the dating of religious texts is very often part of an authority game in which the earlier text is taken to ‘win’ as the reward for a convincing (but unavoidably fallible) scholarly argument. In such cases, it has nothing much to do with the meaning of the text. Claims about dating may become hostages to fortune, and the practical meaning of the text very quickly becomes submerged in scholarly competitiveness. I very much feel that serious pragmatism demands agnosticism about claims that are heavily associated with the authority of texts, at least as the default option.

Overall, then, I think Batchelor’s account of secular Buddhism, though it has the great virtue of engaging many people in a pragmatic critique of Buddhist tradition, leaves a great deal that is of importance still unresolved or unnecessarily open to unhelpful interpretations. One reason for this is that it tries to use the concept of ‘secularism’ for a purpose for which it is ill-equipped. The other is that it remains unclear in practice how committed Batchelor is to a pragmatic interpretation, rather than one that continues (at least implicitly) to rely on tradition through the historical appeal to canonical sources.

Of course, I also think that one underlying reason for these limitations in Batchelor’s account is his neglect of the Middle Way, which really only gets passing mentions here and there, and is never really highlighted as important, despite all Batchelor’s discussion of the character and teachings of the Buddha. As Batchelor was kind enough to write an appreciative foreword for ‘The Buddha’s Middle Way’, I hope this may change in future. The key point missing here so far, though, is that, although Batchelor recognises that metaphysics is a problem, he doesn’t show any recognition that negative metaphysics is just as much of a problem as positive. As negative metaphysics in reaction to positive is such a feature of many interpretations of secularism, this is obviously a crucial reason for being cautious about identifying oneself with it.