‘Indian wisdom has always extolled art as the key in the salvation of ultimate release sought by all good Hindus’. In particular I find Indian miniature paintings very beautiful and colourful, designed with great ingenuity to fit a small space.

In Hinduism the central idea, the philosophy, is that there is a continuing cycle of birth and rebirth as humans search for emotional and psychological pleasure which perpetuates until the soul is freed from karma and reaches Moksha. This complex religion had its roots in India some say as far back as 10,000 years BC. It recognises a single deity Brahman but other gods or goddesses are recognised as an appearance of the supreme god Brahman who is the creator and one in a trinity comprised of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

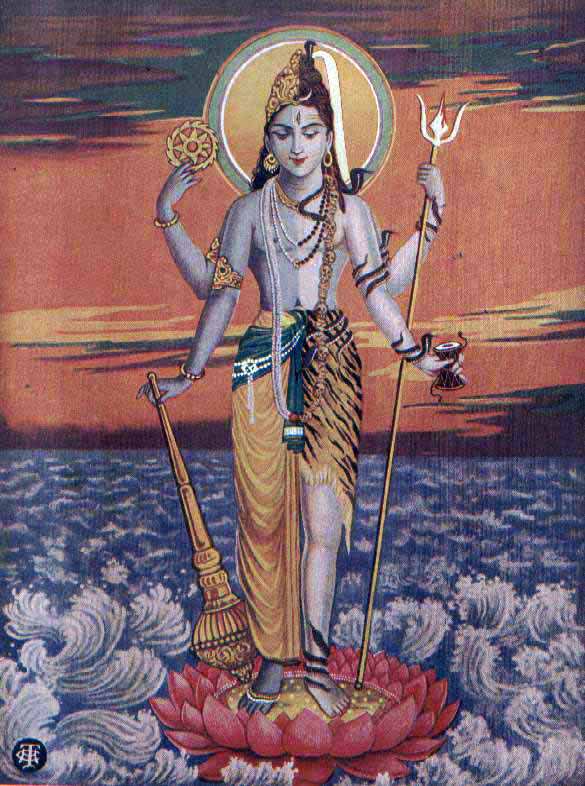

In this painting we see the combination of the two gods, Vishnu and Shiva, creator/destroyer, formed as one figure, the painter explores metaphorically the ground between these extremes, to find a balance, is there middle ground between such opposed roles, that of Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer, a divided self? It is in our power to be both creative and destructive.

Indian art in the Hindu tradition contains a wealth of symbols in a way similar to those used in Renaissance art centuries later. I do not know who painted this or where in India it orignated or its date but it is probably painted in oils. Indian art is found on cave walls, as reliefs, frescoes and scultpture and in many styles.

Vishnu in Hinduism is a popular deity, a Supreme god of the Vaishnavism denomination, one of the three most influential denominations in contemporary Hinduism. He is believed to be eternal and supreme, beyond the material universe, he is the maintainer or preserver who can be worshipped in the form of ten avatars, Rama and Krishna being the most famous, not seen or measured by material science or logic, each Hindu aims to dwell in a place of bliss for eternity. Here the question once again is posed of whether we are finite beings or infinite.

Vishnu is depicted as having a dark complexion like water – filled clouds, usually he is seen with four arms, he stands on a lotus flower, an ancient Indian symbol of purity and special power and is also shown as an example of ‘glorious existence and liberation’, he holds a discus, a mace, a conch and a trident, the lotus flower in this painting is set on a cosmic ocean with a red sky, a sunset or sunrise I’m not sure. Vishnu is married to Lakshmi, they have children who are also worshipped such as Ganesh, the elephant god.

Shiva is worshipped by the Chauvism denomination, the oldest of the major sects of Hinduism, it probably has its roots in Shiva worship in the Indus Valley. He is the other god portrayed whose role is that of the destroyer, he will destroy the ego and the universe at the end of a age, he is also seen as the God of the Dance, he dances the dance of death, he destroys illusions and imperfections making way for beneficial change, he is the source of good and evil and can swing to and fro from hedonist to ascetic. Parvati is his eternal wife, she is able to keep him in balance within the bonds of marriage. We see him portrayed with a blue face and throat and usually he has a white body, although that can also be blue, he has a third eye which depicts his wisdom and untamed energy, he is often seen wearing a cobra necklace to show his fearless domination of dangerous animals, three white lines lie across his forehead drawn with white ash which may hide his third eye, these lines show that he possesses superhuman power and wealth. He holds a three pronged trident to symbolise the triumvirate of the three in one god, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, lastly he is dressed in simple animal skins and is often set in austere surroundings looking tranquil and smiling.

In this portrayal known as Hari-hara, the gods holds a conch shell, a symbol of the five elements, water, fire, earth, air and space or sky, it produces the sound ‘Om’ the primeval sound of creation, a discus which refers to the mind, a trident which I mentioned earlier and lastly the mace which represents mental and physical strength. All aspects of life are covered.

Image from wikimedia commons.

Thanks for this interesting post, Norma, expanding our sphere of artistic interest!

The dominant philosophy in HInduism is monist: that is, the belief that all is one. Not only gods but humans, animals, and the inanimate universe are all ultimately one. This is obviously a metaphysical belief, as we have no way of knowing whether all is ultimately one or multiple, and this painting could be interpreted as an expression of that metaphysical belief. However, I think there is also an experience contributing to the idea of monism, which is an experience of the unity of archetypes. Like other religious paintings, this painting could also be related to our experience of meaning, if we manage to bracket off associated beliefs and think in these archetypal terms.

The two archetypes involved might be seen as different aspects of the God archetype. If the God archetype is our forward projection of the integrated psyche, that imagined integration could be seen both as creative of something new and wonderful, or at the same time as destructive of the limited identifications we have now. This picture could be taken as conveying the ways in which these two kinds of experience are inextricable. To bring it right down to earth, you could think of any occasion when we’re challenged to assimilate something new that’s beyond our current ‘comfort zone’: in one sense that assimilation is creative, and in another it may evoke fear of the destruction of what we feel we already have. Yet the fear and the delight of the new are different sides of the same coin.

Hi,

This is really interesting stuff and it is nice to see some non-european art too.

I like much of the Hindu imagery that I have seen, as I like the mythology – of which I am only partially informed. What I have come across always appears to be more balanced than the ‘western’ religions that I am used to – which all seem to explain the world (and our place in it) in extraordinarily black and white terms. Although I do admit that I might just be seduced by the exotic novelty of it all!

I don’t think that to have a view of oneness has to be metaphysical, although it can be. If we are only dealing with the observable universe, then it is reasonable to suggest that we are connected to everything else – in that way we are separate in some respects but also form part of a whole. I don’t know if this is what is meant in Hinduism though.

I can also see much more value in this image and subject matter as an archetype, or series of archetypes. This firstly comes from my own biases, which consists of a total disconnect to the abrahamic God – who I can only regard as an undesirable and best avoided (in terms of worship and ethical guide) characterisation of a deity. Secondly, I believe that a significant majority of people in the west regard God, not as an archetype but as a deity, who they either believe in, don’t believe in or choose not to bother themselves to much with either position. I have an incling (that could be very wrong) that many Hindus treat their Gods in a much more analogous way. And finally, there seems to be much more subtlety to the Hindu mythology, where things are not just presented as Good and Evil – this seems to represent the human condition with more care and accuracy – again I may have totally misunderstood what I have seen.

Rich

Hi Rich,

The idealisation of the oriental that you suspect of yourself does appear to be in operation! I have made several visits to India and Nepal, and spent two years at university studying Indian languages, and my impression is that Hinduism is no different from any other religion in terms of containing both archetypal resources, and plenty of metaphysical dogmas that have been widely exploited to maintain power.

It would indeed be astonishing if the Hindus did not present things in terms of good and evil – i.e. if they didn’t have a Shadow archetype which was projected onto ‘evil’. There are plenty of dwarf figures representing ignorance being trampled by dancing deities, and then there’s the acute rejection of impurity, institutionalised by the caste system and the ostracism of the dalits. The basis of the caste system is present in the earliest texts – the Cosmic Man of the Rig Veda, the Law Book of Manu that lays down the laws on caste and untouchability, and the Bhagavad Gita that preaches that a person’s moral duty is specific to their caste. The Shadow is largely projected onto those considered impure rather than those considered vicious, but there’s still plenty of projection.

Monism also brings its own forms of intolerance, in the form of the insistence that inconvenient differences be ignored. Buddhists in India are constantly being told that they are really Hindus, not allowed to assert their own identity. The caste system and associated monistic doctrine also supports widespread fatalism of a kind that has been inimical to positive social change in India. No, Hinduism is rich in symbol, but is really not that nice.

Yes, I take your point Robert. I am aware, and disturbed by the continuing presence of the caste system. I have recently spoken to one of my Hindu colleagues (an anaesthetist), who described the treatment of the ‘untouchables’ to me. Despite being a practicing Hindu, she very much disapproved of this system – but saw little chance of it changing any time soon. Having studied Buddhism, I also consider the Buddhas rejection of this as one of the most radical and praiseworthy ideas attributed to him.

Despite knowing this, I can still get seduced by the exotic nature of the mythology and imagery – which comes from an attraction to novelty coupled with ignorance. This seduction would not amount to an attraction to Hinduism as a faith or way of life though, even without the more unpleasant aspects. For a start I would find all the deities distracting, as I do when Zen Buddhists start discussing the Bodhisattvas. I should point out that I like Christian imagery too, the art, literature and mythology inspired by the Bible seems to be infinitely richer and more interesting than the source material.

Religious faith aside, part of what I was trying to say was that as analogies or archetypes, faiths with many characters might have an advantage over those with only one God. By having characters that cover a range of human, and natural characteristics – good, bad and somewhere in between, they might be able to be more neuanced. As opposed to the abrahamic God who is supposedly perfect and the embodiment of goodness, but is also jealous, angry and wrathful.

Rich

Hi Robert and Rich,

Thank you both for your comments on Hinduism, I am delighted when a painting starts a discussion. I studied the subject in the 1970s (not very thoroughly) which led me to take an interest in Buddhism soon after I finished my studies. I wish I had had a tutor Robert, who understood the philosophy and archetypes involved, but better late than never, mine was a retired vicar, he really did not have much of a clue about the Upanishads which we were reading in English, I had to try to fathom them out on my own. I did like their poetic qualities I remember.