This morning, I woke up thinking about what it is that is distinctive about the Middle Way approach that sets it apart from other ways of judging things. To put it more crudely in marketing terms, what is its ‘USP’ or unique selling point? I find that in whatever form I try to convey what the Middle Way is about, many people like to appropriate it into the terms of some tradition or type of thinking that is more familiar to them: for example, Buddhists think of it in Buddhist terms, scientists in scientific terms, and so on. I usually think that they are partially right, but that they are still missing an understanding of what is most distinctive, because synthesis (see different ideas from different sources in relation to each other) is so central to it. So however I try to convey the unique ‘selling point’ of the Middle Way, it will have to be based on a synthesis of different qualities coming together. Those qualities may be found separately in lots of places, but the Middle Way asks one to see them together and in systemic relationship to each other. It starts to arise more fully when they are all brought together.

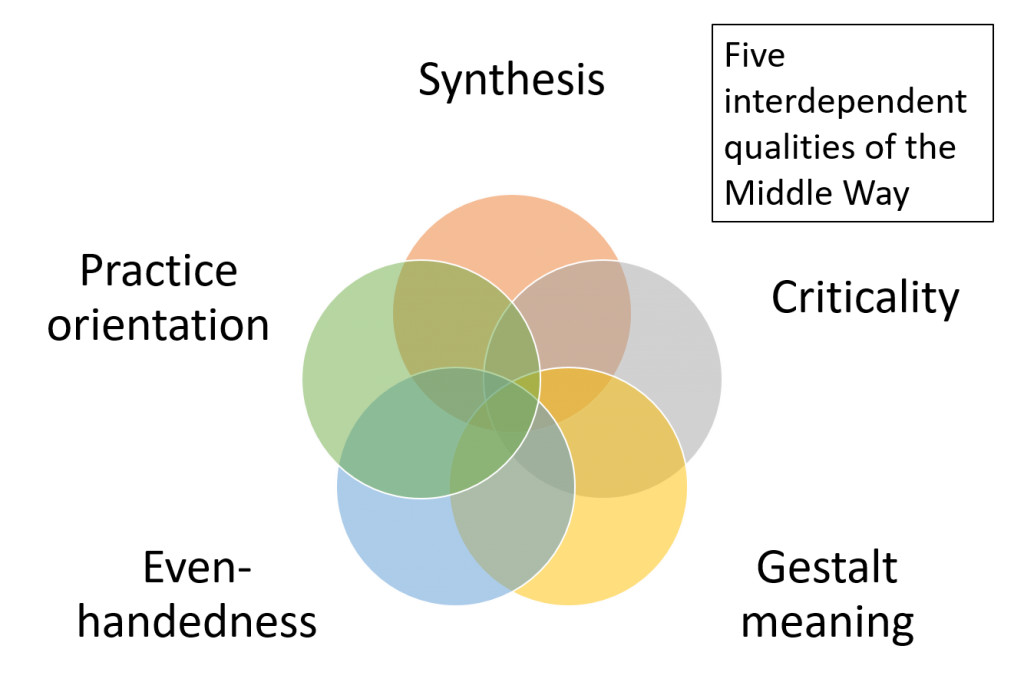

I worked through a list of lots of different viewpoints, along with what I felt they shared and didn’t share with the Middle Way, and by this means managed in the end to distil a list of five qualities. These qualities, when combined and held together, seem to jointly create a distinctive Middle Way approach, whereas in every other approach that seemed to get near to the Middle Way but not quite hit it, I could identify one of these qualities missing. Of course, in those approaches that are even further from the Middle Way, there will be more than one of them missing. Focusing on these qualities is thus a different (but hopefully complementary) angle from which to understand the Middle Way than the Five Principles that I have been using for some years now. Lets call them the Five Qualities. the five qualities that I identified were synthesis, criticality, gestalt meaning, even-handedness and practice orientation. The diagram below conveys that interdependent aspect.

Firstly, synthesis is the ability to bring ideas together from different places. Without that ability, provisionality, in which we are open to alternative possibilities, is impossible. Synthesis is blocked by domain dependence, where our thinking is stuck in one context where we are used to applying it: for instance, we don’t apply what we learnt at work when we get home. Fixed and essentialised categories can also block synthesis, by making us think in only one way that’s dictated by the framing of the language we’re using: for instance believing that ‘religion’ must be only ever be one kind of thing. The blocking of synthesis is also, in my view, a major problem in academia, where it results in over-specialisation, over-reliance on analysis alone, and relativism about values. Those academic ways of framing things also influence the rest of society.

Secondly, criticality is the ability to question the current set of assumptions that we are making or are presented with. Even if we are theoretically aware of alternatives, if it doesn’t occur to us to consider the possibility that what we believe might not be true, we can be slaves to confirmation bias, locked into an unhelpful set of assumptions. For instance, people who are mystically inclined may have a highly meaningful, practical and synthetic approach to things, but they also often assume that this view offers ‘ultimate truth’ of some kind. Their failure to apply any criticality to this assumption can again trap them in unhelpful views in practice.

Thirdly, gestalt meaning refers to the recognition of symbols being meaningful because of our embodied experience, channelled through the right hemisphere. This meaning is gestalt because it comes to all at once in an intuition, rather than being conveyed piecemeal. However, when we assemble these gestalt meaning experiences into language through the use of schemas and metaphors, we can use them to express our beliefs, and at that point they become subject to criticality. So putting criticality together with the recognition of gestalt meaning results in the distinction between meaning and belief, and the recognition that we need to treat them in slightly different ways: to appreciate and celebrate meaning, but maintain critical awareness about our beliefs. Many people find this difficult, or are not even aware that it is possible: thus there are many spiritual and artistic people with a strong sense of gestalt meaning but little criticality, and many scientifically or philosophically educated people who are inclined to dismiss anything to do with gestalt meaning as “woo”, because they wrongly assume that it must be a kind of belief that threatens their justified and critical scientific beliefs. An insufficient openness to gestalt meaning can impoverish our emotional and imaginative lives, and tends to lead us into representational and instrumentalist attitudes in which, for instance, we don’t really respond to others as people like ourselves.

Fourthly, even-handedness is another quality that we need to be able to apply when we are engaging in synthesis, criticality and appreciation of meaning. There are always many different possibilities jostling for our attention, and many different possible beliefs we could adopt. Even-handedness is the capacity to apply a model of balance in our judgements about these, not simply immersing ourselves or committing ourselves to one kind of meaning or belief and completely neglecting another. This is especially important when it comes to dealing with absolute or metaphysical beliefs, as it is so easy to reject one because of its dogmatism without recognising that you are running headlong straight into the arms of its opposite (like people ‘on the rebound’ from a relationship breakup). Even-handedness requires an emotional awareness that the degree of hatred that is likely to accompany your rejection of one view does not have to create a total desire for only one alternative to it.

Finally, practice orientation is the commitment to making your judgements practical and putting them into practice. That will probably mean that you are ‘working on yourself’ through some kind of integrative practice such as meditation, the arts, and/or study, and probably also ‘working on the world’ through some kind of communicative, social or political activity. With practice orientation you are always likely to be asking ‘does this really make a difference in practice?’ and thus have a critical perspective on purely theoretical accounts that take abstract completion as an end in itself. For instance, if someone makes you an argument about the nature of the historical Jesus, you can ask what difference this makes: is it going to change the way that Jesus functions in people’s lives, as a source of advice, inspiration, or archetypal meaning? There are many academic approaches that seem to lack this kind of practice orientation, because they have turned scholarly or scientific investigation within a particular field an end in itself.

Of course, this list may not be complete, and may still be improved upon. But perhaps it can provide another way into the Middle Way, but especially into the question of what is distinctive about it. If you’re not sure about how well a particular approach fits the Middle way, you might like to start by asking whether all five of these qualities are present, at least to some degree.