Cosmopolitanism is the belief that one is a citizen of the world, not just of one particular piece of it that happens to have been sectioned off in a particular fashion by geological movements or medieval bloodshed. Such a position could be over-idealised, but I think it could also be understood as a realistic and balanced position that addresses wider conditions as well as more immediate ones. What’s more, I very much feel we need more cosmopolitan thinking in the UK at the moment, where the media is often consumed in a blaze of narrow arguments about the EU, leading up to the June referendum on membership. Almost all these arguments, even those of the ‘remain’ camp, concentrate overwhelmingly on an assumed national interest. But personally, when I vote on June 23rd, I shall do so not just as a citizen of the UK, but also as a citizen of the EU and of the world.

Almost all these arguments, even those of the ‘remain’ camp, concentrate overwhelmingly on an assumed national interest. But personally, when I vote on June 23rd, I shall do so not just as a citizen of the UK, but also as a citizen of the EU and of the world.

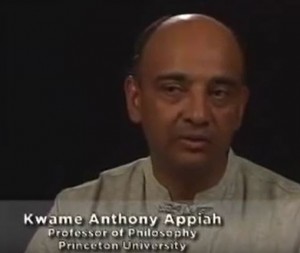

In this video, Kwame Anthony Appiah (a philosopher working in the US, who is descended from Ghanaian chiefs on one side and Sir Stafford Cripps, UK cabinet minister, on the other) gives a persuasive account of cosmopolitanism and its advantages.

As Appiah explains here, Cosmopolitanism recognises the value both of our commonality with the whole world, and of cultural difference. His most important message is that our moral concern does not and should not end at national borders. Why should it, when national borders are the arbitrary results of geography, past conflict, and absolutised tribal, linguistic or religious difference? Borders of any kind are an attempt to absolutise differences that are merely incremental and that (however strong they may be) in any case do not necessarily require separate political organisation. Borders are also a political reality that we have to adapt to, but hardly one that we should be spending our energy strengthening when there are so many better places to put that energy. As the Pope memorably said recently with reference to Donald Trump’s wall-building aspirations, we should be building bridges, not walls.

As with any ideology, there is a risk that cosmopolitanism could become idealised and absolutised. It could start to ignore the political borders that do operate, and the even more important psychological condition of people’s limited identification. It may well be that the EU has made some misjudgements based on such idealism, particularly its admission of Greece to the Euro without adequate scrutiny of its long-term financial stability. Integration of the world needs to be incremental, and cannot proceed too much in advance of the integration of the individual people who are its citizens. The EU has made some astonishing achievements in integrating Europe both politically and culturally during the past 50 years or so, but it probably needs a period of consolidation now, for the people and their culture and economic life to catch up with it. However, the EU’s mistakes, such as they are, are hardly an argument for reversing many of its achievements by withdrawing one of its most Important states from the union.

If we focus on a recognition of our embodiment and its limitations, that may seem to bring with it a more localised focus, recognising the strengths of our immediate environment and culture. But a localised culture is not necessarily a parochial culture that tries to separate its interests from those further afield. Our embodiment is also a source of universality, as we have pretty much the same basic body and brain structure as all other humans throughout the world. All that we have to do to recognise our cosmopolitanism is to recognise our embodied humanity, and to give it more importance than narrow tribal identity. If you want to look more beyond narrow tribal identity, then look to the influences you expose yourself to. For example, your media sources: populist UK newspapers like the Daily Mail will expose you to the assumptions of narrow tribal identity day after day, and I’m sure there are similar sources in other countries. Don’t assume that such narrow sources won’t have an effect. It will have an effect because you have a body, rather than being a disembodied reason that can consider every issue afresh at every moment.

I do think that cosmopolitanism is an ideological approach that could quite readily be an expression of the Middle Way in most cases, provided we are careful not to absolutise it. For most of us, dogmatic nationalism is a far greater danger in practice than dogmatic internationalism, and cosmopolitanism combines an internationalist outlook with a full respect for cultural difference and localised autonomy. I think it is only through such an outlook that, in the longer-term, it is possible to address the conflicts in the world adequately. I also see the EU, whatever its short-term errors or limitations, as a cosmopolitan institution whose founding principles of internationalism linked with subsidiarity try to follow that balance. So there are not too many prizes for guessing which way I will be voting on 23rd June.

NB. This article has been reproduced by a site called ‘Multinational News’. Please note, if you have come here from that site, that ‘Multinational News’ has pirated this article without permission from the author.