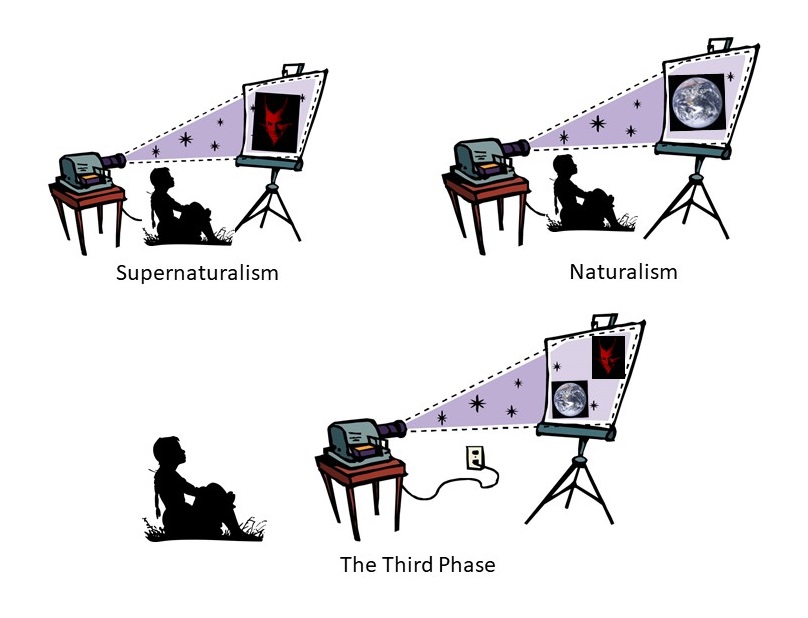

Back in 2013, I wrote a post on this site called the Third Phase. This suggests that, although nothing in history is inevitable, there do seem to be some signs that our civilization as a whole may be entering a new phase of engagement with conditions. You could see that as a new kind of science, philosophy, psychology, or practice. Here is the crucial part of that post that explains the three phases:

In the medieval era, complexity was ignored because of the over-simplifications of the ‘enchanted world’ and its unresolved archetypes. We mistook projections of our psychological functions for ‘real’ supernatural beings. A supernatural world provided a causal explanation for the world around us that prevented us from needing to engage with its complexity. The medieval era was gradually succeeded by the era of mechanistic science, in which linear causal mechanisms took the place of supernatural ones. Although we began to get to grips with the processes in ourselves and the universe, this was at the price of over-estimating our understanding of them, because we were using a naturalistic framework according to which, in principle, all events could be fully explained.

We are now gradually moving beyond this into a third phase of intellectual development. In this third phase, we not only develop models to represent the universe, but we also recognise and adapt to the limitations of these models. We take into account not only what we know, but what we don’t know. The signs of this third phase have been appearing in many different areas of intellectual endeavor.

Look at the original post for a list of what those areas are. They include complexity theory, embodied meaning, brain lateralization, and cognitive bias theory. These are all relatively new developments, involving psychology and neuroscience, that come together to offer the basis of a new perspective. But that perspective is not entirely dependent on them, and is actually far older, since it is another way of talking about the Middle Way. The Third Phase may arguably have first been stimulated by people living as long ago as the Buddha and Pyrrho.

What strikes me, looking back at this idea more than three years after the original blog, is how simple and obvious it is. The idea of being aware of our limitations is not at all a new one. It’s just the product of the slightly bigger perspective that I’ve tried to illustrate in the diagram above. You can merely be absorbed in the ‘reality’ you think you’ve found, probably reinforced by a group who keep telling you that’s what’s real, or you can start to recognise the way that this ‘reality’ is dependent on (though not necessarily wholly created by) your own projective processes. You look at that hated politician and see the Shadow. You look at scientific theories based on evidence about the earth and see ‘facts’. Or you can look at yourself seeing either of them, and also recognise that those beliefs are subject to your limitations. In both cases that doesn’t necessarily undermine the meaning and justification of what makes the politician hated or the theories highly credible. It just means that you no longer assume that that’s the whole story.

The third phase is not simply a matter of the formalistic shrugging-off of our limitations. It’s not enough just to say “Of course we’re human” if the next moment we go back to business as usual. The third phase involves actually changing our approach to things so as to maintain that awareness of limitation in all the judgements we make. I think that means reviewing our whole idea of justification. In the third phase, we are only justified in our claims if those claims have taken our limitations into account. That’s the same whether those claims are scientific, moral, political or religious. So it’s really not enough just to claim that such-and-such is true (or false) just because of the evidence. People have a great many highly partial ways of interpreting ‘evidence’, and confirmation bias is perhaps the most basic of the limitations we have to live with.

So far people have only really dealt with this problem in formal scientific ways, but science is like religion in being largely a group-based pursuit in which certain socially-prescribed goals and assumptions tend to take precedence, even if very sophisticated methods are used in pursuit of those goals. Such scientific procedures as peer review and double-blind testing are not the only ways to address confirmation bias, and they are applicable only to a narrow selection of our beliefs. The third phase, if it is happening, is happening in science, but it is also very much about letting go of the naturalistic interpretation of science: the idea that science tells us about ‘facts’ that are merely positively justified as such by ‘evidence’. In the third phase, science doesn’t discover ‘facts’, but it does offer justifications for some beliefs rather than others, and these are acknowledged as having considerable power and credibility. In the third phase, that is enough; we don’t demand an impossible ‘proof’. Better justified beliefs are enough to support effective and timely action (for example, in response to climate change).

The third phase involves a shift in the most widely assumed philosophy of science, but it is not confined to science. It is also a shift in attitude to values and archetypes. Some of us are still caught up in the first, supernaturalist, phase as far as these are concerned, and others in the second or naturalistic phase. Ethics and religious archetypes are either assumed to be ‘real’ or ‘unreal’, absolute or relative, rather than judged in terms of their justification and the limitations of our understanding. I do have values, that can be justified in my context according to my experience of what should be valued. At the same time, the improvement of those values also involves recognizing that they are dependent on a limited perspective that can be improved upon, just as my factual beliefs can be.

Perhaps what I didn’t stress sufficiently in my first post on the topic is that the third phase is not a matter of clearly-defined scientific breakthroughs. It is individuals who can start to exercise the awareness offered by the third phase with varying degrees of consistency. As Thomas Kuhn wrote of scientific breakthroughs or paradigm shifts, they actually depend on a gradual process of individuals losing confidence in an old paradigm and shifting to a new one. But there can also be a tipping point. When it starts to become expected for individuals to recognise the limitations of their justification, as part of that justification itself, social pressure can begin to be recruited to help prompt individual reflection.

We can hope for some future time when the third phase is fully embedded. When religious absolutists stop assuming that the way to make children more moral is to drill them in dogmas. When secularists get out of the habit of dismissing whole areas of human experience in their haste to find a secular counterpart to religious ‘truth’. When promoting understanding of the workings of our brains is no longer considered suspiciously reductive. When the public is so well educated in biases and fallacies that they complain to journalists who let politicians get away with them. When evolutionists respond to creationists not by appealing to superior ‘facts’, but solely by pointing out deficiencies in the justification of creationist belief, in ways that apply just as much in the realm of ‘religion’ as in that of ‘science’. Yes, we are still a long way off the entrenchment of the third phase. We can only try to get it a little more under way in our lifetimes.