Over-specialisation, with its attendant false dualities between different areas of thought, is in my view a major issue of our time. It even affects our widespread current inability to face up to the climate crisis, as the authority of specialised experts is such a matter of conflict wherever scientists have to communicate unpalatable findings to the wider population. Surely, I often reflect, if we had a slightly more adequate education system in which both critical thinking and general psychological awareness featured more strongly, it would be a good deal harder for opportunistic denialists to gain such a popular following, and the politics of facing up to difficulty would be at least a bit easier? There are potential future ways of healing the rift – if we have a future, that is.

From time to time, though, I find contemplating the current and likely future situation too much to bear, and take refuge in the past. The past, particularly, before all this specialisation – of the gentleman scholar and the polymathic clergyman. In no way do I want to idealise the past, but it does show us in some ways, not only that things can be done differently, but that they have been. The difference is nearly always that in the past, the things that were better only applied to a very small minority, whereas now our expectations have risen to such an extent that we expect everyone to share in any improvement. When I look (with a temptation of nostalgia) at a less specialised past I have to keep reminding myself of this. Nevertheless, the intellectual integration that some groups managed in the past can still potentially be developed by a wider population in the future.

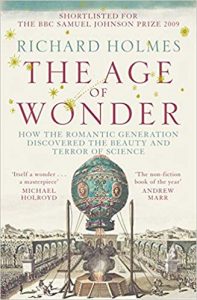

My appreciation of a pre-specialist past has been boosted recently by reading a book by Richard Holmes (best known as a biographer of Romantic English poets), called ‘The Age of Wonder’, published in 2008. This book offers an account of a crucial phase in the development of science (focusing especially on Britain), from around 1770 to around 1830, but also highlights its constant connections with the Romantic movement. It may come as news to many that during this period all scientists, as well as other thinkers, were still known as ‘philosophers’, as they were in ancient Greece. Such great figures as Joseph Banks (botanist and anthropologist), Humphrey Davy (chemist) and William Herschel (astronomer) described themselves as ‘natural philosophers’. Herschel was also a musician and Davy a poet. Davy was a close friend of Coleridge, Southey and other poets: the arts and the sciences actually talked to each other and maintained an integrated view of the world!

has been boosted recently by reading a book by Richard Holmes (best known as a biographer of Romantic English poets), called ‘The Age of Wonder’, published in 2008. This book offers an account of a crucial phase in the development of science (focusing especially on Britain), from around 1770 to around 1830, but also highlights its constant connections with the Romantic movement. It may come as news to many that during this period all scientists, as well as other thinkers, were still known as ‘philosophers’, as they were in ancient Greece. Such great figures as Joseph Banks (botanist and anthropologist), Humphrey Davy (chemist) and William Herschel (astronomer) described themselves as ‘natural philosophers’. Herschel was also a musician and Davy a poet. Davy was a close friend of Coleridge, Southey and other poets: the arts and the sciences actually talked to each other and maintained an integrated view of the world!

The theme of wonder, that gives the title to the book, is an important one. Poets and scientists were united by wonder, and wonder is an open emotion implying a strong continuing access to experiential right hemisphere perspectives. Though of course none of these figures were free of dogmatic assumptions, their sense of wonder, and their social sharing of it, could provide a check to the tendency of a specialised theoretical perspective to assume that its view of the world provides a total explanation. Not only did this make these great early scientists apparently open to new forms of discovery, but it also made them much more flexible in their use of their expertise than one would expect from a modern academic. Sir Humphrey Davy not only pioneered our understanding of the constituent gases of the atmosphere, the carbon cycle, and the isolation of substances like chlorine and iodine through electrolysis, but he also developed a safety lamp that greatly reduced the likelihood of coal miners dying in gas explosions. Today that would be considered the work of a technologist, not a scientist, but in Davy’s day there were no such distinctions.

There was wonder, too, in William Herschel’s astronomical achievements. Not only did he discover Uranus, but he was also the first to recognise the vast distances between the Earth and the stars, together with the existence of galaxies. He did this partly by developing larger and better telescopes, but also (on his own account) by just learning to look at the stars. Observation became not just a matter of passively watching, but rather a matter of actively altering your method of observation so that the visual data coming through the telescope made sense. There was wondering receptivity as well as theoretical expectation there, in a form that can add to our confidence that Herschel was not merely observing what he wanted to observe. We can never entirely rid ourselves of confirmation bias, but we can definitely make a difference.

In the hands of these inspirational early scientists, science often seems like a Middle Way practice – one in which we are constantly adjusting our view of the world in the light of new experiences and perspectives, rather than seeking only to confirm or deny. Of course, there are also many modern scientists who take this approach. There are also far more educated people in the population able to understand what they do than there were in 1830. Nevertheless, it seems to me that something important has been lost, not always in individual attitudes, but primarily in the educational and academic system that frequently isolates those individuals from each others’ perspectives. Academics can usually only compete effectively in their specialised niches by hardening their assumptions to fit the social expectations of that discipline. The relentless managerialist emphasis on ‘efficiency’ of research in modern academic life also removes much of the leisure enjoyed by those in the Age of Wonder, and so further closes the doors of wider exploration.

There are also many signs of a thirst for a return for that lost interdisciplinarity today. Recently I was intrigued to learn of the launch of the London Interdisciplinary School, due to open its doors in 2020 to an entirely interdisciplinary cohort of students. They were looking for founding faculty, so I applied, but I’ve since heard that they had 612 applications for 6 places. I thus don’t expect to be successful, but this tells you something about how much pent-up longing there is to get back, in some sense, to the age of philosophers worthy of the name (ones who are not just experts in Dismissiveness Studies).

The Age of Wonder is after all still going on, and will continue as long as we are capable of wonder. We’ll be capable of wonder as long as we can reach out beyond our own little niches of assumption – whatever they are. As long as we’re capable of wonder, we’ll also be capable of creative discovery.