This enhanced podcast, part of the series on meaning from the summer retreat, provides a short introduction to archetypes of just 6 minutes.

Category Archives: Religion

Buddhism and the Middle Way Audio

The first lot of talks from our August retreat is now up, enhanced by pictures. These three linked sections of talk introduce the Middle Way from the perspective of people whose background is in Buddhism, explaining some of the Buddha’s teachings about the Middle Way, the conflicts between the Middle Way and other principles in Buddhism, and the traditional interpretation of the Middle Way in Buddhism and its limitations. Go to this page.

Franciscan saintliness

How do we understand the role of saints in relation to the key idea of the Middle Way – i.e. to avoid metaphysics? After all, these people had very real virtues that many people testify to, yet they were steeped in metaphysics. Aren’t they a counter-example to the thesis that avoiding metaphysics is morally and spiritually preferable? I don’t think so, but to explain why will require a bit of exploration of an example. For my example I have chosen St. Francis, as I read his biography (by Adrian House) a little while ago.

St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) is a figure that it is easy to admire, or at least respect. He wasn’t a grisly martyr or a captain of the inquisition, but rather he was renowned for his humility, tranquillity and wisdom. As an alternative to the corrupt monastic orders of his day, he created a new brotherhood and sisterhood – the Franciscans and the Poor Clares. He also had intense religious experiences, and courageously tried to bring peace to Egypt during a Crusade by crossing the enemy lines and speaking directly to the Sultan that the Christians were fighting. However, throughout that time he remained completely obedient to the Holy Catholic Church and its metaphysical dogmas.

Didn’t Francis do pretty well on metaphysics? And how could he possibly have “avoided” metaphysics? Francis can here represent a host of other figures, throughout the ages and including the present, in a similar position. The idea that we should consider the influence of metaphysics on such figures to be a bad thing rather than a good thing requires a complete reassessment of our ideas about religion and morality, to an extent that many people find incomprehensible.

It will become comprehensible only when we look a bit more closely and carefully at what is involved in the idea of a person having a metaphysical belief. The idea of committing one’s life to a metaphysical belief is one that has become dominant, not only in religion, but also in some areas of politics, art and beyond: but it is delusory. Somebody who ran their life entirely on the basis of a belief that bore no relationship to experience would not be able to respond to their experience, because they would have no models available to them that were compatible with that experience. Experience throws up all sorts of specific practical challenges that require specific beliefs. All-encompassing metaphysical beliefs are no use for this. Knowing that God is love does not help you identify which mushrooms are poisonous, or even which friends you should trust.

Thus, we can be confident that even the most committed saint does not in fact run their lives on the basis of metaphysical beliefs. Instead, they have a number of models of the world around them that they construct either directly from experience, or from the models given to them by others in the course of their socialisation and education. Included in these models are metaphysical ones. Deeply rooted in a metaphysical belief is the idea of the ultimate importance of that belief: but experience does not bear out such a claim of self-importance.

In the case of St. Francis, then, we would expect his main beliefs to be ones about the practical world in which he lived: for example, the lasting and solid nature of objects such as walls and tables; beliefs about social relationships and of what sorts of behaviour were acceptable and unacceptable in medieval Assisi; or beliefs about the political rule of the Dukes of Spoleto and the negative effects of questioning their power. The fact that Saint Francis also believed strongly in the existence of God, that Jesus was the Son of God, and that the Pope was the representative of God on earth, did indeed have important effects on Francis’s life, but that does not mean that they were the only or even most practically important beliefs that he held.

Let us take St. Francis’s virtues of tranquillity, humility and wisdom, which Francis himself (and presumably most modern Christians) would attribute to his strong belief in God, Christ and the Church. Yet Francis’s actual experiences relating to these things would have come through prayer, in which he may have attained highly integrated states, from a sense of meaningfulness in his whole life, and through encounters with the Church, its clergy and the Pope. When having a religious experience, Francis would have strongly associated this with metaphysical beliefs – but the meaning of this experience was a direct physical one, as we can see from the embodied meaning theory. The experience itself could not have been based on metaphysical ‘truths’, because these ‘truths’ were themselves constructed through metaphor on the basis of prior physical experience. Rather, the metaphysical ‘truths’ were a rationalisation created by the habitual thinking of his society and projected onto his religious experience. Francis’s encounters with God would be encounters with an archetypal symbol of integration in his deepest experience, not a metaphysical belief appealing to concepts. His religious experiences were so physically immediate that he is said to have received the stigmata (marks of Christ’s wounds) and to have walked on burning coals unharmed: whether these happened in a more literal or a more symbolic way we do not know, but if they did happen in a way that others witnessed they can hardly have been the result of a merely abstract metaphysical belief – rather of an experience that possessed his entire being.

So Francis’s virtues would have come, not from his metaphysical beliefs, but from his more basic experience of integration. Temporary experiences of integration, especially when experienced deeply on a regular basis, as they are by some meditators, are a wonderful source of tranquillity, of a kind that could keep Francis content with extreme self-imposed poverty. They are also a source of wisdom, because they provide a wider perspective on experience that can help judgement take into account a wider range of conditions. This experience of integration would also keep the edges of his cognitive models supple and malleable in a way that would enable him to accept correction by others and recognise his own limitations: in other words give him humility.

Francis was a saint not because of, but despite, his metaphysical beliefs. The very fact that he could emerge in the context of medieval Catholicism tells us something of the strengths of that tradition. The virtues of integration were admired, even though there was a good deal of confusion about their source. It was possible, in fact, to believe that metaphysics was good and ordinary physical experience was evil – the exact opposite of what I would argue to be the actual case, and to make that belief stick. But at the same time, people would actually make most of their judgements based on ordinary physical experience – including many of their moral and religious judgements.

How has such a belief been made to stick for so long? I can only suggest that this is because it had an adaptive value in maintaining group loyalty. People maintained their loyalty to the Church in medieval times, and this loyalty helped them to live together with limited conflict, as well as uniting them against enemies that would otherwise have defeated them. There is nothing better than an apparently unquestionable belief for maintaining loyalty and group identity.

However, this apparently positive effect of metaphysics comes at a price. We can see that price illustrated in Francis’s own life. Unable to question the Pope’s authority, he remained at the mercy of papal whims. Deeply committed to the ideal of poverty as an end in itself based on the self-sacrifice of Christ, Francis got into conflict with other early members of his order who wanted a slightly less ascetic lifestyle in which a few more of their needs could be met. Francis had his weaknesses, and we can trace each of these directly to an appeal to metaphysical authority.

More widely, the medieval society in which Francis lived suffered from its obsessive relationship to metaphysics. Conflict was created both internally (e.g. putting down of heresies such as the Cathars) and externally (e.g. the Crusades). The scientific advances that had been made in Classical times were largely forgotten, continued and developed only in the (at that time) slightly less rigid Islamic world. Political rule remained autocratic, society stratified, education and learning extremely limited. New ideas were dangerous and ideological change very slow. The medieval world is a warning to us of what a society dominated by metaphysical commitments might be like. Nevertheless, it was neither unchanging, nor incapable of creating striking innovators like St. Francis.

I hope from this example, the possibility of avoiding metaphysics might become a little clearer. Metaphysics is not a basic set of assumptions that we can’t avoid, as some claim. We do often make such basic assumptions, but it’s our business to question them and hold them provisionally as far as we can. Nor are metaphysical beliefs responsible for our virtues. We do all have them, to a greater or lesser extent, and will not be able to give them up all at once. However, an incremental approach can work in shifting our energies from metaphysical beliefs to non-metaphysical ones.

St. Francis himself may have got about as far as he could in avoiding metaphysics, given that he lived in such a deeply metaphysical society. So part of the effort in avoiding metaphysics may take place at a social and political level. For example, if we were no longer indoctrinated into metaphysical views from early childhood, this would no doubt help us in avoiding them. However, each of us is placed in a situation now in which we have certain metaphysical influences and certain non-metaphysical influences. We need to work with whatever we have, from wherever we start.

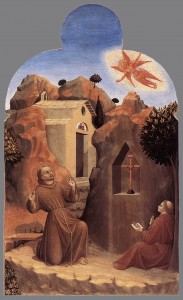

But there is no reason today why we should not be inspired by the virtues of Saint Francis. Every time I visit the National Gallery in London I enjoy the paintings of his life by Sassetta, which are all part of the San Sepolcro Altarpiece (one of these illustrated). The saint has a symbolic value for me that I find difficult to explain, beyond a broad understanding in Jungian terms that he is an instance of a Wise Old Man archetype. Somehow seeing fifteenth century depictions of him strikes much deeper than any later depiction could do.

The MWS Podcast: Episode 2, Norma Smith

In the first of a series of member profiles, retired art teacher Norma Smith talks to Barry Daniel about her life, why she became a member of the society, the middle way, the importance of art in her life, agnosticism, and the power of metaphor. With regard to the latter, she was especially enthusiastic about the work of George Lakoff. Please see link to a youtube talk he gave on metaphors as embodied meaning below.

In the first of a series of member profiles, retired art teacher Norma Smith talks to Barry Daniel about her life, why she became a member of the society, the middle way, the importance of art in her life, agnosticism, and the power of metaphor. With regard to the latter, she was especially enthusiastic about the work of George Lakoff. Please see link to a youtube talk he gave on metaphors as embodied meaning below.

George Lakoff: Frameworks, Empathy and sustainability

There is also a slide show version of the podcast available on Youtube.

Reconsidering the Fall

I have been thinking recently about the Fall – no, not the leaves falling off the trees, in American parlance. I mean the story in the book of Genesis of the Bible, about how Adam and Eve ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, then were expelled from the Garden of Eden by God. Just mentioning this story may raise the hackles of secularists, who associate it with metaphysical dogma. However, I think there is an important distinction to be made between metaphysical claims, which are dogmatic, and stories and symbols, which are not. To make a claim like “Adam and Eve made all humans sinful” is metaphysical, and we can see the negative effects of the Christian dogma of Original Sin in terms of psychological conflict. However, to tell and re-interpret the myth of the Fall so as to relate it more usefully to experience is a different matter.

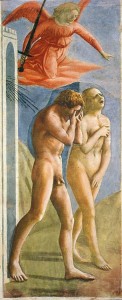

The myth is a potent one. Take this very famous picture by Masaccio of the expulsion from Eden. For me this communicates a very basic experience of suffering and links it powerfully to a sense of exclusion. The story is exploring the meaning of human suffering through creating a story about its causes. Obviously, the way these causes are symbolised is to some extent dependent on the culture of the early Hebrews in which the story developed. However, one would also expect it to tap into more universal human experiences. How we interpret the story in terms of these is something we can play around with. I’m going to offer an interpretation which I think helps to relate the story to universal human experience. That doesn’t mean that I think that’s what the story is “really” about (the “really” would take us back into metaphysics). Rather it’s an interpretation, which I take responsibility for as such.

Let’s think about the basic elements of the story. It divides roughly into three: (1)God creates the Garden of Eden, (2) Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit, and (3) then they are expelled.

If we take a Jungian interpretation of God and his meaning, he represents the integrated psyche, just as a Buddhist mandala does. God is a represented idealised form of how we would be if we were entirely free of conflict, internal or external, and we may associate this symbol with people we know or have heard of who may have got further on this road than we have – Wise Old Men and Wise Old Women. The Garden of Eden, said to be created by God, bears a similar interpretation. It is an idealised symbol of complete contentment through full integration.

However, this garden-mandala contains the seeds of conflict – the tree of knowledge of good and evil. I think one helpful way of interpreting this would be as the ego, or the obsessive function of a detached left hemisphere of the brain. When we eat the fruit (develop the representational functions of the left hemisphere) we gain power and insight because we are able to manipulate the world to our own ends far better than we were before. We can use language to make plans, instructions, warnings etc and communicate them to others. We are capable of gaining an increasingly coherent view of the world in which we act. However, this ability also comes at a price – the tendency of the left hemisphere to absolutise, to believe that it has the whole picture, and to turn its beliefs into metaphysical ones. This might be thought of as ‘knowledge of good and evil’ because of the ego’s tendency to accept and reject things dualistically, thinking of what it happens to like at the moment as ‘good’ and what it dislikes as ‘evil’.

By eating this forbidden fruit, then, we create suffering as well as power, because we exclude ourselves from the degree of integration between the hemispheres we might have otherwise. We emerge from an undifferentiated and implicit awareness into a world of concepts – a process that can be disorientating and alienating. We have been thrown out of the garden because we no longer feel whole in the sense that we might, and yearn for a missing integration.

One of the early church fathers, Irenaeus, described the sin of Adam and Eve as felix culpa, a ‘happy sin’. This suggests that he was getting to grips with the contradictions involved in the Fall. We feel shut out, but we also feel empowered by the ego and its associated conceptualisations. He perhaps implicitly recognised that the ego is not a bad thing to be destroyed, but the basis on which we can develop further. However, stretching the ego so as to gradually dilute its weaknesses requires effort and practice: we can’t rely on a salvation from the effects of the Fall from Christ, as the metaphysical doctrines of Christianity have it.

The story of the Fall is such a basic part of Western culture, that it would be a great shame to merely shut it out by dismissing it as ‘untrue’, as some secularists appear to do. ‘Truth’ is really not a relevant test to apply in understanding what this story – or any story – has to offer. I would suggest that the Middle Way here involves finding creative ways to engage with it and harness its power – whether that is through the kind of interpretation I am suggesting or some other way. Even if we also recognise its limitations, every myth can speak to us in some way.