I’ve been thinking recently about creation in human experience, and also how this relates to the symbolism of creation in the Bible. I’m indebted to Iain McGilchrist here, who, in ‘The Master and his Emissary’ points out the difference between left hemisphere and right hemisphere forms of creation: I will call them reproductive and mimetic forms of creation. The more I reflect on this difference the richer it seems.

In the reproductive form of creation, some kind of idea, plan, or copy (whether mental or physical) of what is to be produced already exists. A new version of that copy is produced.

However, in the mimetic sense of creation, something already exists that may have a closer or more distant resemblance to the thing to be created: it may just be ‘raw material’ that is to be shaped, but in accordance with how it already is. The existing materials are recombined so as to produce something new that was not previously combined in that way, whether in the object itself or in the mind of the creator.

The crucial differences between these forms of creation depend on what is going on in the mind of the creator.

In the reproductive sense of creation, there are clear goals and representations of what is to be created, and the process of creation is merely to reproduce those goals as precisely as possible. The representations may or may not include an actual copy of the thing to be produced already in existence. A construction engineer building a bridge from a set of painstaking designs in creating in this sense, as is a factory production worker who merely controls a machine that is pre-set to reproduce identical plastic parts over and over again. In this sense of creation, the left hemisphere is heavily dominant.

Reproductive creation follows a positive feedback loop in which an idea is fixed on, a copy of that idea is constructed, and then the constructed thing reinforces the idea. However, reproductive creation will only actually succeed to a certain extent. The plastic parts may appear identical, but will have microscopic variations. The bridge may follow the specification as precisely as possible, but there will be at least some small divergences from it. However, the mental state accompanying this kind of creation focuses on the goal of copying, and will either be frustrated by a lack of exactness in the copying or will deny that there is any such lack, re-interpreting the creation to fit the idea and pretending in ad hoc fashion that it was intended to be like that all along. Any divergence from the plan, if it is admitted, is a failure. The view of the world adopted is one where it is assumed that it is possible to copy exactly because there is an absolute relationship between the specification and the creation. Whilst it may be admitted, on philosophical enquiry, that the copy in the plan is not exactly the same as the created thing, the reproductive creator will insist on the absoluteness of the relationship. This relationship can be called isomorphism from the Greek for ‘same shape’.

In the mimetic sense of creation, on the other hand, there is no expectation of any isomorphism between a plan or a previous model and what is created. Rather it is accepted that both the form of what is created and its meaning to us will depend on various variable factors: the nature of the materials, the mental state and expectations of the creator, or other incidental factors that contribute to what is produced. It is not that the creator will lack plans or intentions, for these will always have to be present to some extent for the activity of creation to occur at all. However, it is accepted that the creation will in some respects have a life that is independent of the creator. Different goals may emerge in the process of creation that were not envisaged at the beginning. A wider harmony and integrity will be sought for the creation which is only partially in line with any wishes the creator may have started with, also responding to the conditions that arose in the process of creation.

In contrast to the positive feedback loop involved in reproductive creation, mimetic creation involves a negative feedback loop. An idea of what is to be made is put into operation, but differences between the idea and the creation are not seen as failures, rather as new conditions to be learnt from and responded to. In this way the idea of what is being created continually changes along with the thing being created.

The mimetic sense of creation is obviously one that applies to works of art, following the senses discussed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Erich Auerbach. It also applies to parenthood – at least if it is pursued with wisdom rather than with inflexible plans for the child. Mimesis is obviously the embodied type of creativity. It is a type of creativity pursued with an active and integrated role for the right hemisphere, taking new conditions into account as well as the left hemisphere’s goals and representations. We tend to describe people as ‘creative’ who have learnt to manage the process of mimetic creation with confidence.

I don’t want to imply here that reproduction is necessarily bad: it is just limited when compared to mimesis. The problem with reproduction seems to be when it is absolutised: when we expect copies to be exact, and plans to be precisely reproducible. There are some horrendous examples in history of big plans that were put into operation with hardly any consideration for the conditions: perhaps the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme is the most astonishingly arrogant and incompetent example I have come across. Mimesis, on the other hand, is not only a quality of the best art, but also the best political proposals and the best engineering projects, among many other things.

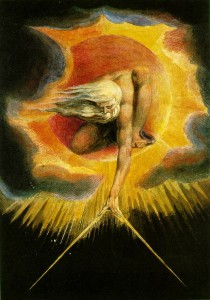

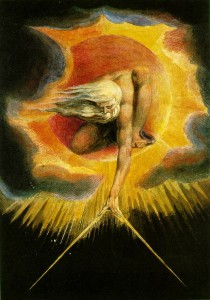

If you apply these ideas about Creation to God’s creation of the world in Genesis, they can be related to the debate about what sort of creation Genesis is describing. Did God simply have a plan that he put into operation regardless? If so, we could read the Creation story as a left hemisphere fantasy of the total and precise enactment of a plan, based on total power. This way of thinking seems to be implied in the classic Christian interpretation of the Creation as ex nihilo – that is, as creating something out of nothing. Blake’s famous ‘Ancient of Days’ picture depicts this kind of creation.

But the text begins “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was a vast waste, darkness covered the deep, and the spirit of God hovered over the surface of the water.” (Gen 1:1-2), which can on the contrary be read as indicating that earth, ‘the deep’ and water already existed, and were merely formed by God. This interpretation would fit the influence of Babylonian and other near eastern creation stories on this one, as the other stories all involve prior existent matter.

If we try to let go of all the metaphysical claims and associations with Christian (and Jewish) dogmas in the Genesis story, we can read it archetypally and in accordance with human experience, simply as an inspiring symbol of creativity, with an archetypal God as a cosmic artist. God does have plans, but he also has raw materials and unexpected conditions to respond to. He pauses each day after making each new set of things before continuing, suggesting that he wasn’t just putting his plans into operation without reflection. What’s more, if you’re creating something as complex as life, you must expect it to respond in unexpected ways: as Adam and Eve are depicted as doing. For more on the Eden story, see my previous post, ‘Reconsidering the Fall’ (and also don’t miss Emilie Aberg’s excellent comment on that).