Cycles are an easily identifiable feature of universal human experience. Arguments go ’round in circles’. Efforts to change get caught in vicious circles or Catch 22s. Buddhism has its Wheel of Samsara (or ‘Wheel of Life’), in which craving leads to frustration and then more craving. Various social sciences identify various cycles: the economic cycle, the political cycle, the cycle of addiction, the cycle of violence, the cycle of poverty and degradation, and so on. What do these cycles have in common? Are they inescapable?

One interpretation I want to resist from the start is the belief that these cycles are inescapable (or alternatively, only escapable through some miraculous supernatural cause) because ‘natural’. The cycles I’ve mentioned so far all depend on the human brain, so we have no reason to conflate them with other sorts of cycle that are entirely (rather than debatably) beyond human control – such as eco-cycles, planetary cycles, or the cycle of birth and death. Though they may share some formal features with other kinds of cycles, the kinds of cycles I want to focus on here are within the sphere of human judgement: and that’s a sphere in which the extent of our responsibility remains perpetually vague and unresolved.

What the cycles within that sphere seem to have in common is their relationship to looped synaptic tracks in the brain. Broadly, we can see our feedback loops as leading from the older ‘reptilian’ lower brain, where our basic motives arise, to the pre-frontal cortex in the front of our brains, where we conceptualise and contextualise in a more distinctively human fashion. But this understanding of the situation then gives rise to new motives, looping us back to the back of the brain. We ‘go round in circles’ when we are in the habit of following certain entrenched synaptic tracks, in which certain kinds of desires give rise to certain kinds of beliefs, that then reinforce the desires and again reinforce the beliefs. For example, Marc Lewis shows this process in the brain of an addict in his book The Biology of Desire, reviewed here. As Lewis points out, it’s not only drug addicts that go through such feedback loops, but to some extent all of us.

We also go through such cycles over a shorter period of time when we ‘ruminate’: going through a proliferating cycle of thoughts that are usually motivated by obsession or anxiety. If you keep thinking the same thoughts over and over again and can’t get to sleep, or can’t focus on work or meditation, you are probably caught in a positive feedback loop.

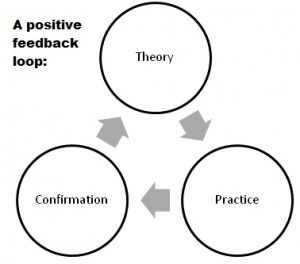

Positive feedback loops are the means by which we can set up good habits as well as bad ones, and as long as we are in a stable environment in which those habits are helpful, relying on them isn’t too much of a problem. However, if we want to be able to adapt to ever-changing new circumstances, we need to be able to move out of unhelpful positive feedback loops of this kind. Where they become conceptualised in the left pre-frontal cortex, these loops are the basis of confirmation bias: we tend to just seek out evidence that fits the beliefs we already have, rather than challenging those beliefs – and this tendency is the basis of all sorts of other errors.

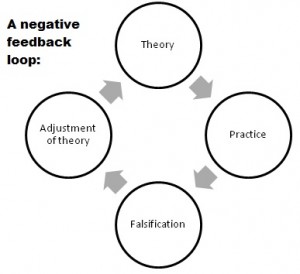

We have good evidence from experience that we are able to move out of such positive feedback loops, by responding to new experiences that challenge our beliefs, and thus adapting our beliefs to fit new circumstances. Instead of a positive feedback loop in which an old habit is reinforced, this is then a negative feedback loop in which learning and adjustment can take place. However stuck in our ways we may be, we have all done this lots of times in the past, especially as children. The human brain retains its plasticity well into old age – and thus we are always capable of changing our beliefs, even if we find the process uncomfortable. To get out of a circular argument, then, or even an addiction or an economic cycle or a cycle of violence, we just need to be willing to learn how to do things differently.

I sometimes think that if this wasn’t called the Middle Way Society, it could be called the ‘Negative Feedback Loop Society’. It’s that basic to what the Middle Way is about. For the extremes avoided by the Middle Way are rigid or absolutised beliefs of a kind that resist change and maintain themselves only in the context of positive feedback loops. In the Middle Way, or as Ed Catmull memorably calls it the ‘messy middle’, we are able to be creative, to switch strategies, to adapt.

Some people are confused by the labels, assuming that a ‘Negative Feedback Loop’ must be bad because it’s negative. But it’s negative only in the sense that it challenges and catalyses change – not necessarily emotionally or logically negative. Similarly, there’s nothing necessarily ‘positive’ in an emotional sense about positive feedback loops: indeed the repression that they often bring with them is likely to stifle any sense of joyfulness and replace it with alienation and boredom in which the energy of possible alternatives is dimly felt but nevertheless denied.

In some formulations of Buddhism (such as that of Sangharakshita), the Wheel of Samsara (which may be interpreted along the lines of such an addictive cycle) is accompanied by a Spiral. A spiral gives graphic expression to the idea that we might continue to go round and round to some degree whilst lifting out of those habits in other respects, and is thus one way of symbolically representing the process of moving out of positive feedback loops and into negative ones. However, the Spiral is often represented as though it was a single absolute path culminating in the transcendent point of nirvana, and on that interpretation, at least, it seems to be incompatible with the Middle Way. Negative feedback loops are a different pattern of judgement, but one that we might find in the thick of a complex pattern of positive feedback loops, and it is the nature of the judgement that is important rather than the ultimate destination.

Positive feedback loops, like samsara in Buddhism, should not be seen as intrinsically bad, but they are limited, and a set of beliefs that rigidly limits us to such loops does then become morally inferior when compared to alternatives that allow us to adapt to a wider range of conditions. We do not need to deduce this from a supposed standpoint of nirvana, or any other supposed absolute beyond experience. It should be clear to us as long as we are willing to simply compare a relatively flexible standpoint to a relatively inflexible one.