Almost everything we do is in some way an attempt to improve on what went before. Even tidying up a room involves what we see as an improvement on its previous state. When we consider traditions of human thought and activity, too, each new development of a tradition tries to address a new condition of some kind and thus also remedy a defect: for example, the Reformation was a response to dogmatic limitations and perceived abuses in the Catholic church, and new artistic movements respond to what they see as the aesthetic limitations of the previous movements that inspired them.

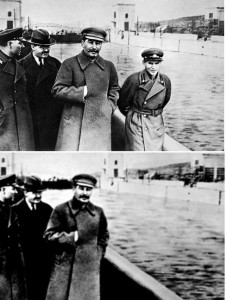

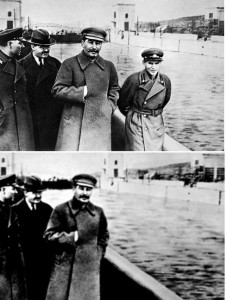

In many ways, then, its not surprising that both individuals and groups gradually evolve new ways of doing things in response to past tradition or custom. What creates a problem, though, is when we essentialise that tradition and try to appropriate its whole moral weight to justify our current approach: believing that we have found the ultimately right solution, the true answer, or the ultimately correct interpretation of that tradition. When we do that, we’re not just contributing to a new development that we acknowledge to be different from what went before, but also imposing that development on the past. In effect, we’re projecting the present onto the past.  This is an approach to things for which ‘revisionism’ seems to be a good label, though it’s most typically been used for those who more formally impose their preconceptions on the interpretation of history, such as holocaust deniers. This photo shows such revisionism in action in the Soviet Union: the executed commissar Yezhov removed from a photo featuring Stalin.

This is an approach to things for which ‘revisionism’ seems to be a good label, though it’s most typically been used for those who more formally impose their preconceptions on the interpretation of history, such as holocaust deniers. This photo shows such revisionism in action in the Soviet Union: the executed commissar Yezhov removed from a photo featuring Stalin.

In a sense, we’re all revisionists to some degree, since this tendency to appropriate and essentialise the past is wrapped up in common fallacies and cognitive biases that we might all slip into. We’re especially likely to do this when considering our own past, for example underestimating the extent to which our mature experience differs from our youth and projecting the benefit of hindsight onto our judgements in the past. In working on my next book Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief, I’ve been thinking a lot about these cognitive biases around time recently. There are many concerned with the present and the future, or with non-specific times, as well as the past, so I won’t try to discuss them all, but just a couple that focus particularly on the past.

In terms of Critical Thinking, the fallacy of absolutising the past is equivalent to the Irrelevant Appeal to History or Irrelevant Appeal to Tradition. This is when someone assumes that because something was the case in the past that necessarily makes it true or justified now. Simple examples might be “We haven’t admitted women to the club in the hundred years of our existence – we can’t start now! It would undermine everything we stand for!” Or “When we go to the pub we always take turns to pay for a round of drinks. When it’s your round you have to pay – it’s as simple as that.”

A common cognitive bias that works on the same basis is the Sunk Cost Fallacy, which Daniel Kahneman writes about. When we’ve put a lot of time, effort, or money into something, even if it’s not achieving what we hoped, we are very reluctant to let go of it. Companies who have invested money in big projects that turn out to have big cost overruns and diminishing prospects of return will nevertheless often pursue them, sending “good money after bad”. The massively expensive Concorde project in the 1970’s is a classic example of governments also doing this. But as individuals we also have an identifiable tendency to fail to let go of things we’ve invested in: whether it’s houses, relationships, books or business ventures. The Sunk Cost Fallacy involves an absolutisation of what we have done in the past, so that we fail to compare it fairly to new evidence in the present. In effect, we also revise our understanding of the present so that it fits our unexamined assumptions about the value of events in the past.

I think the Sunk Cost Fallacy also figures in revisionist attitudes to religious, philosophical and moral traditions. It’s highly understandable, perhaps, that if you’ve sunk a large portion of your life into the culture, symbolism and social context of a particular religious tradition, for example, but then you encounter a lot of conflicts between the assumptions that dominate that tradition and the conditions that need to be addressed in the present, there is going to be a strong temptation to try to revise that tradition rather than to abandon it. Since that tradition provides a lot of our meaning – our vocabulary and a whole set of ways of symbolising and conceptualising – it’s clear that we cannot just abandon what that tradition means to us. We can acknowledge that, but at the same time I think we need to resist the revisionist impulse that is likely to accompany it. The use and gradual adaptation of meaning from past traditions doesn’t have to be accompanied by claims that we have a new, true, or correct interpretation of that tradition. Instead we should just try to admit that we have a new perspective, influenced by past traditions but basically an attempt to respond to new circumstances.

That, at any rate, is what I have been trying to do with Middle Way Philosophy. I acknowledge my debt to Buddhism, as well as Christianity and various other Western traditions of thought. However, I try not to slip into the claim that I have the correct or true interpretation of any of these traditions, or indeed the true message of their founders. For example, I have a view about the most useful interpretation of the Buddha’s Middle Way – one that I think Buddhists would be wise to adopt to gain the practical benefits of the Buddha’s insights. However, I don’t claim to know what the Buddha ‘really meant’ or to have my finger on ‘true Buddhism’. Instead, all beliefs need to be judged in terms of their practical adequacy to present circumstances.

This approach also accounts for the measure of disagreement I have had with three recent contributors to our podcasts: Stephen Batchelor, Don Cupitt and Mark Vernon. I wouldn’t want to exaggerate that degree of disagreement, as our roads lie together for many miles. and in each case I think that dialogue with the society and exploration of the relationship of their ideas to the Middle Way has been, and may continue to be, fruitful. However, it seems to me on the evidence available that Batchelor, Cupitt and Vernon each want to adopt revisionist views of the Buddha, Jesus and Plato respectively. I’m not saying that any of those revisionist views are necessarily wrong, but only that I think it’s a mistake to rely on a reassessment of a highly ambiguous and debatable past as a starting-point for developing an adequate response to present conditions. In each case, we may find elements of inspiration or insight in the ‘revised’ views – but please let’s try to let go of the belief that ‘what they really meant’ is in any sense a useful thing to try to establish. In the end, this attachment to ‘what they really meant’ seems to be largely an indicator of sunk costs on our part.