A firefighter and a stockbroker were old friends from school. They met at a school reunion, and started talking about the pros and cons of each of their jobs.

“Of course it’s dangerous,” the firefighter was saying, “But after a while in the job you get really good intuitions, so you tend to know what’s really dangerous and what isn’t.”

“Intuitions?”

“Yeah, you just know without having to think about it, because you’ve seen it all before so many times. You just know when a building’s about to collapse, for example, and you have to get out fast. And you can tell when it’s reasonably safe to try to get someone out of a fire, and when it isn’t so you’ve probably lost them. It doesn’t help anyone for you to die as well.”

“So do they always work, the intuitions? Do people get caught out?”

“Sometimes, but probably less than you’d think. It’s often the younger ones, the one’s with less experience, that get it wrong. For me, now I’ve been doing it for fifteen years now, it’s like a sixth sense. I couldn’t ignore when my sixth sense is telling me a roof’s about to fall in than I could ignore something I saw or heard.”

“But do you see and hear things that set it off? Like creaks?”

“Oh yes. But there’re different kinds of creaks. Some of them are dangerous creaks and others not so dangerous.”

The stockbroker reflected, “There are intuitions in my job, too.”

“Oh yeah?”

“You have to know which stocks are going up and which are going down. You’re using market information and trends of course, and information about the performance and financial position of each company, but those don’t tell you for sure what’s going to happen. You can’t just work it out by reasoning. You need an intuition of which stocks are going to be successful.”

“And does it work for you?” asked the firefighter, obviously expecting that it would.

“Well, quite often. I’ve had some very good results. But of course there are some times everyone gets caught out, like in the crash of 2008.”

At that moment another old friend sat down beside them. They both remembered him, and they briefly reminisced about school-days, before mentioning what they were doing now.

“So what are you doing these days?” the firefighter asked the newcomer.

“Oh, I’m a psychologist. Not the shrink type who’ll fix your head, but a research psychologist. I work in a university finding out more about what makes people tick in general.”

“Sounds fascinating” said the stockbroker. “Before you joined us we were just talking about intuition in our different occupations. Turns out both of us rely on it quite a lot – me for stocks rising and falling, and him for burning buildings and when they’re going to collapse. Is that the sort of thing you research?”

“As it happens, yes,” replied the psychologist. “The nature of intuition is certainly one of my interests. The best evidence seems to suggest that it’s more reliable in a smaller set of predictable conditions.”

“What do you mean?”

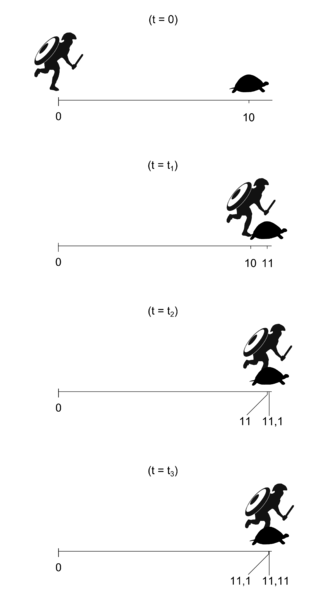

“So, I guess intuition works quite well for experienced firefighters because burning buildings work in similar ways. If there’s a reasonably small range of conditions you might meet, and you learn how to spot them, that then quickly becomes unconscious and automatic. Burning buildings don’t vary that much. Is that how you’ve experienced it?”

“Spot on” said the firefighter. “That’s more or less what I was just saying.”

“And what about stockbroking?” asked the stockbroker, “Do psychologists have anything to say about that?”

“Er, well, I don’t want to cause offence, but let me just report what my colleagues have found about it. They checked statistics of stockbrokers’ predictions against market outcomes and found them worse than random. That means stockbrokers’ intuitions, on average, and of course I don’t know anything about present company, are worse than guesswork.”

“Worse than guesswork?” the stockbroker was incredulous, “But my colleagues are all highly trained and experienced, and we research the markets very carefully.”

“I don’t doubt it, but the evidence seems to be that it’s not that kind of work that makes the difference. There’s just a lot of luck involved. The market conditions are just not very predictable – not like burning buildings. You can only develop reliable intuitions if there’s something reliable to learn from that’s reasonably stable.”

“I can’t believe it. Our results have been consistently good, apart from 2008 of course.”

“Then I’m afraid the research I’ve looked at suggests you’ve been consistently lucky. It’s not just stockbrokers, but people in general tend to consistently overrate how much difference their skill makes to their outcomes, and underrate how much of it is just luck. Think of novelists – we all think the ones who are lucky enough to become well-known are great writers, but there are lots of equally good novelists who aren’t so lucky, and may not even have got published at all. Publishers think they have good intuitions for who will make a good writer, but usually the ones they pick become known as good writers because they’ve been lucky enough to be picked.”

The stockbroker was obviously having some difficulty absorbing this information. Suddenly he spotted another old friend across the room. “Hey, there’s John! Excuse me, I must just go and have a word with him.”

*****************************************************************************************

Intuition

Intuition is a faculty that is frequently appealed to, and often seems mysterious. People may have intuitions about the future, about the right thing to do, about an artwork or project, about a great truth they believe in, or about other people’s feelings. Quite frequently, though not always, these intuitions are wrong. Certainly where intuitions about the future is concerned, where it can be precisely measured whether they turn out to be true – they are not. The work of Philip Tetlock gives lots of information about how unreliable, for example, political and social forecasting generally is.

However, as the example of the firefighter suggests, we cannot just dismiss intuition as a source of information. What is often not sufficiently recognised is that intuition is not an alternative to experience as a way of justifying your beliefs, but just an efficient shortcut for accessing a lot of experience quickly. If you have lots of informative experience from the past that is liable to be applicable to the present situation, then intuition is a great way to get in touch with it. By accessing it unconsciously you’re liable to be able to see the benefit of your experience all together, rather than having to clumsily think about one event and then another event. You are experiencing your past synoptically through the right hemisphere rather than piling up individual past instances in the left. Thus not only is the experienced firefighter’s intuition liable to be accurate, so is a sense of the likely feelings of someone you know well. However, if on the other hand you try to use your intuition to detect the feelings of someone you’ve just encountered on the internet, who is not even a physical presence but rather just a few words on a screen, you are very likely to be way off.

What intuition isn’t, and cannot be, is a mysterious hotline to the truth. Moral or aesthetic intuitions are likely to give you quick access to what your previous experience has informed you. An experienced art dealer might be able to tell that a painting is a fake, or a person brought up in an environment where right and wrong were fairly clear may intuit that a certain action ‘just feels wrong’ based on that previous experience. So again, if that previous experience is reliable with regard to the present, then intuition is useful. However, it’s not likely to be useful in a new and unfamiliar situation, and it certainly won’t give you universal moral or aesthetic certainties.

In situations where we may be used to using intuitions, but where the conditions are new or unpredictable, we really need to slow down and think things through. If we don’t know what’s going on then we need to admit it, or if we can understand things better by research and reflection, then we need to engage in those things rather than relying solely on intuition. The intuitions may still be there, but we’ll have a more helpful sense of their fallibility. For stockbrokers to practise their trade honestly, they may need to state that the value of their service consists mainly in offering convenient share-trading, rather than that the judgements they make on behalf of their clients are likely to make them any richer than they would have been from random investment.

Intuition, then, is not an exception to the need to make only provisional judgements based on experience. We cannot arrive at absolute metaphysical views using intuition, any more than we can by any other means. The Middle Way in relation to intuition obviously thus involves us avoiding such absolute claims based on it. Nevertheless, we can appreciate the value of intuition and make use of it within the sphere in which it operates well.