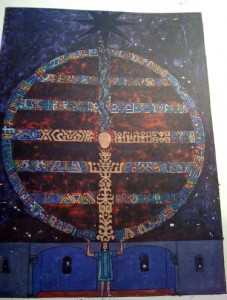

He sees the tree of life, whose roots reach into Hell and whose top touches Heaven. He also no longer knows differences: who is right? What is holy? What is genuine? What is good? What is correct? He knows only one difference: the difference between above and below. For he sees that the tree of life grows from below to above, and that it has its crown at the top, clearly differentiated from the roots. To him this is unquestionable. Hence he knows the way to salvation.

To unlearn all distinctions save that concerning direction is part of your salvation. Hence you free yourself of the old curse of the knowledge of good and evil. Because you separated good from evil according to your best appraisal and aspired only to the good and denied the evil that you committed nevertheless and failed to accept, your roots no longer suckled the dark nourishment of the depths and your tree became sick and withered. (p.359-360)

Here Jung gives what for me is a brilliant summary of the basis of Middle Way ethics. A frequent theme of the Red Book is that of recognising the depths and integrating what we take to be evil. In this sense we go ‘beyond good and evil’ (to use the phrase also used by Nietzsche in his book of that name). To go beyond good and evil sounds to many like relativism or nihilism, leaving us adrift without any justifiable values. But what is required instead is a recasting of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ that takes into account our degree of ignorance, recognising that much of what we reject as ‘evil’ is bound interdependently with what we accept as ‘good’. Instead of rejecting good and evil altogether, we need to understand a more genuine or integrated form of ‘good’ as lying beyond our current understanding, and ‘evil’ only as that which prevents or disrupts integration.

If we focus only on the uncertainty in our current understanding of good and evil, and take that uncertainty to be a negative thing, we will miss the positive implications that Jung brings out in his image of the Tree of Life. The crown of the tree, he tells us, is clearly differentiable from the roots. This would be the case only in terms of experience, not conceptual analysis, because the difference between the crown and the roots is incremental. Nevertheless integrative progress is part of our experience. There may be some adults who have got irredeemably stuck in one set of rigid beliefs and thus stopped growing, but this can hardly ever be the case for children: if we compare ourselves as toddlers and as adults, we have all made some sort of progress, addressing conditions better than we did then. The crown is thus differentiable from the roots, even though there is no absolute point of change in between.

It is also telling that Jung writes “To unlearn all distinctions save that concerning direction.” The new good is a direction, not an absolute, because we do not have full understanding of it and cannot pin it down just by intellectual analysis. Even God as encountered in our experience (as discussed in the previous blog) is a symbol for a direction: the direction of integration in which we only get better, not ultimately good. That also implies that we cannot deduce that direction from any account of an ultimate goal, such as the Buddhist Nirvana. There can be no final goal, for such a goal would be irrelevant to us. As Jung writes in another place:

Not that I know anything about what my distant goal might be. I see blue horizons before me: they suffice as a goal. (p. 276-7)

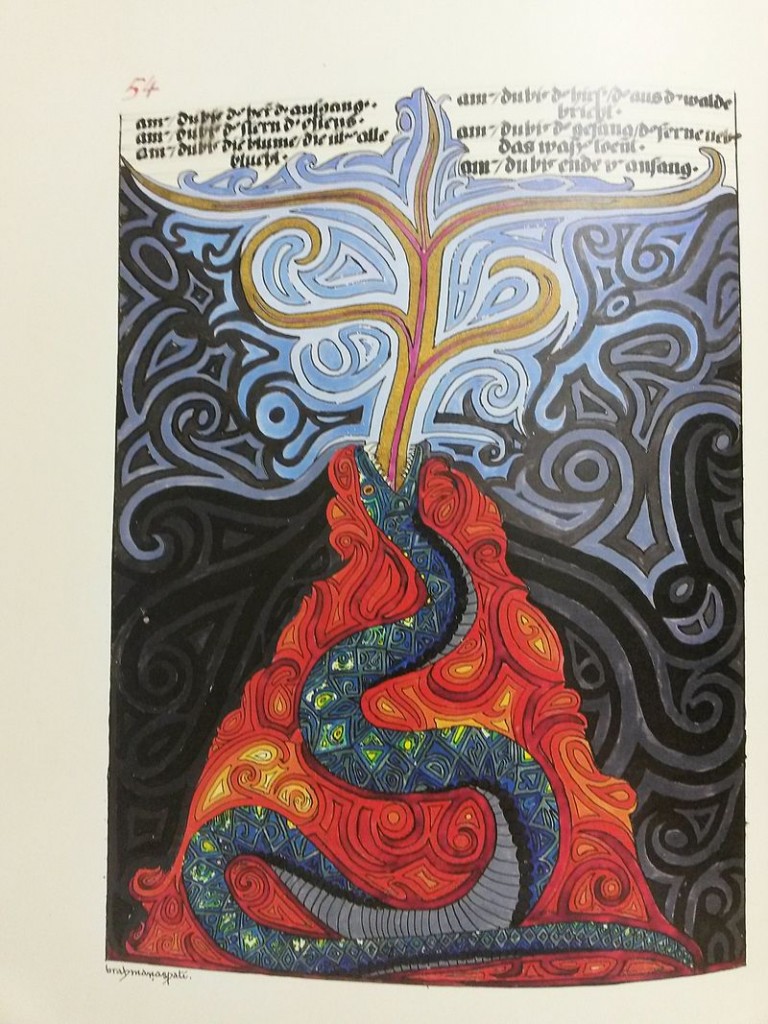

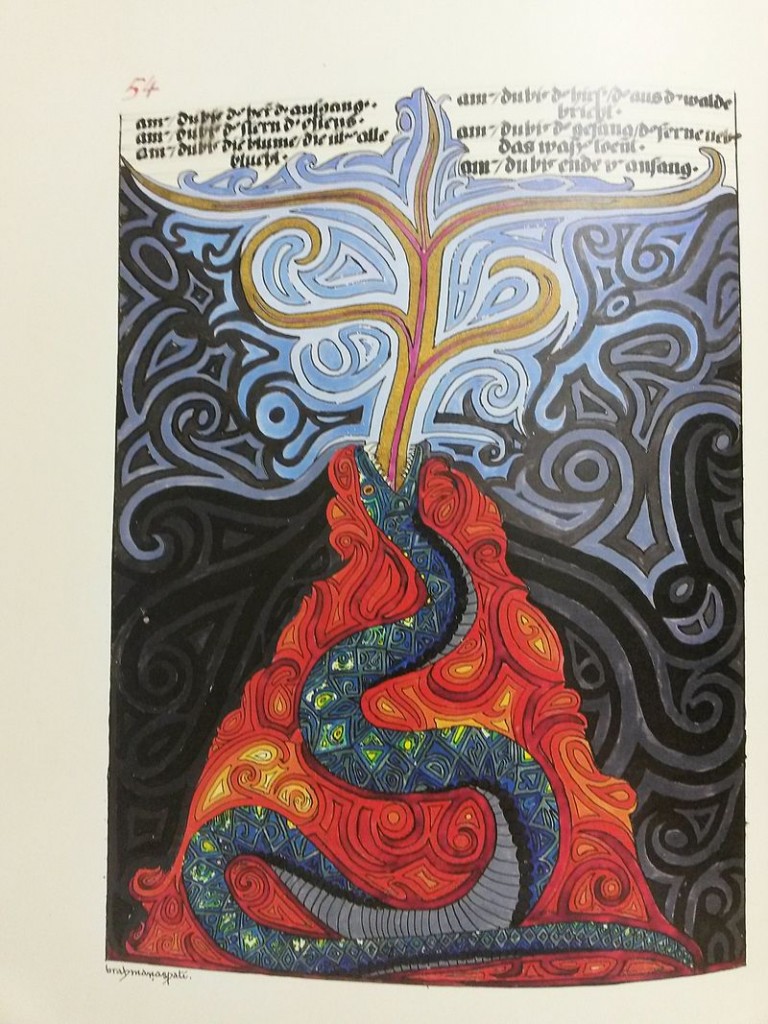

The roots of the Tree of Life are nourished by every aspect of our organic experience, whether by ‘good’ or ‘evil’ as normally understood. This point is also put very graphically later in the text, where Jung shows his utter disgust with the devil at the same time as a reluctant recognition that the devil is necessary. He describes the devil as having a ‘golden seed’.

He emerged from the lump of manure in which the Gods had secured their eggs. I would like to kick the garbage away from me, if the golden seed were not in the vile heart of the misshapen form. (p.424)

This passage tells us something about how difficult it is in practice to face up to the integration of the Shadow. Think of everything you most loathe: paedophiles, Daesh, Donald Trump. Then try to get your head around the way that they have gained control of things that are necessary for you. To start with, your representations of such figures are yours – take responsibility for them. It’s your inner Donald Trump that you hate, not the one out there. The energy that you’re putting into hating your inner Donald Trump is your energy: don’t let him steal it from you. You need to reclaim it from Donald Trump and put it to better use.

But if we are to integrate ‘evil’ without falling into relativism, there also still needs to be a genuine evil that we recognise. Such evil consists in whatever stops the Tree of Life from growing, whatever interferes with the integrative process. That’s where I would draw conclusions that go beyond Jung, but to me seem to be implied by Jung’s insights. That is that what blocks the integrative process is absolutisation. Absolutisation is found in our rigid beliefs, whether positive or negative, which prevents us from responding to new experience and benefitting from it. A given belief is only a part of us, so no person is wholly evil, nor is any tradition or organisation. However, metaphysical beliefs poison the Tree of Life.

This new account of evil is not wholly distinct from the old evil. I think it can be shown how existing common conceptions of evil show the features of absolutisation, and I have explored this in a previous blog as well as in my book ‘Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief’ (section 3.n). Evil is associated with power, despotism, egoism, greed, cruelty, obsession, manipulativeness, defensiveness, rigidity, impatience, pride, short-termism, literalism, despair, emotional impoverishment, and false emotion. Some of these qualities are found in Jung’s experience of evil as found in the Red Book, such as Jung’s encounter with the mocking and sardonic ‘Red One’. All of these kinds of qualities can also be associated with narrow over-dominance of the left hemisphere of the brain when we make judgements.

So it’s not that we have been wrong in our instincts about what sorts of qualities are evil – the problem is only in how we apply those instincts. We have assumed evil to be something external to us, consisting in whole people, objects or institutions, when instead it is to be found in the beliefs that poison the Tree of Life. We need to learn to separate the beliefs from the people: to stop projecting the Shadow onto others, or onto external supernatural forces, and recognise it as an archetype in ourselves.

Another implication of the image of the Tree of Life is that its growth will happen regardless (as a result of life) if it is not interfered with. As long as the roots can get their nutriment without hindrance, we do not have to make the tree grow towards good. However, preventing the hindrance to the roots may take much more deliberate action. If someone were to try to pour poison on the roots we would have to actively stop them. That’s why I think we can’t take the process of integration for granted, but rather need to be on the alert and using our critical faculties to detect and avoid absolutisations. That’s why the practice of the Middle Way, the avoidance of absolutisations on both sides, is not just a matter of innocent effort. It also takes a degree of educated cunning. We cannot just tell those who want to absolutise that they are entitled to their opinion and leave it at that, but whenever we can do so fruitfully we need to contest, not them, but their opinion. Even if we fail to convince others, we need to free ourselves of the shackles of intrinsically rigid ways of thinking.

You should be able to cast everything from you, otherwise you are a slave, even if you are the slave of a God. Life is free and choose its own way. It is limited enough, so do not pile up more limitation. Hence I cut away everything confining. I stood here, and there lay the riddlesome multifariousness of the world. (p.378)

Previous blogs in this series:

Jung’s Red Book 1: The Jungian Middle Way

Jung’s Red Book 2: The God of experience

Picture: from Jung’s Red Book (Xabier CCSABY 4.0)