This oil painting was first exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1844, it now belongs to the National Gallery, London. Turner was 76 years old when Rain, Steam and Speed was exhibited. As a young man he lived with his father in London, who would prepare his canvasses and varnish the work when completed, he was deeply affected by his father’s death in 1830, his mother had become insane in later life and her illness may have formed Turner’s melancholy nature, the death at 28 of his friend and fellow painter Thomas Girtin also affected him deeply. During his lifetime he had witnessed many changes in society as a result of the Industrial Revolution, I have chosen the steam train as a metaphor for this transformation from a mainly agrarian society to an industrial one. He moved many times, having lived in Harley Street, Queen Anne Street and in Hammersmith, he liked to live near water and moved later to a house in Twickenham. He is famed for his seascapes, he would go out in wild seas on board boats and for his landscapes painted in Britain and Europe. His life was dedicated to painting in oils and watercolours and he left many sketches to the nation, he remained single. Turner began his working life painting wash backgrounds and skies on architectural drawings, once he became well known he became a tutor at the Royal Academy and painted many commissions for wealthy patrons like Lord Egremont who lived in Petworth, some of his paintings still hang in Petworth House.

The train in this painting ran on the Great Western Railway, one of a number of privately owned railways, this line ran from Taplow to Maidenhead, then over the Thames on a bridge built by I K Brunel, heading towards East London. Railways had evolved since the first engines were built in the early 17th century, trains pulled wagons which ran on wooden rails to carry coal from mines to canals, where canal boats were pulled by horses along tow paths to the growing towns. Cast iron rails were replaced by stronger wrought iron tracks. By the 1850s people as well as goods were being transported by trains as they became popular and there was plenty of coal to fuel them.

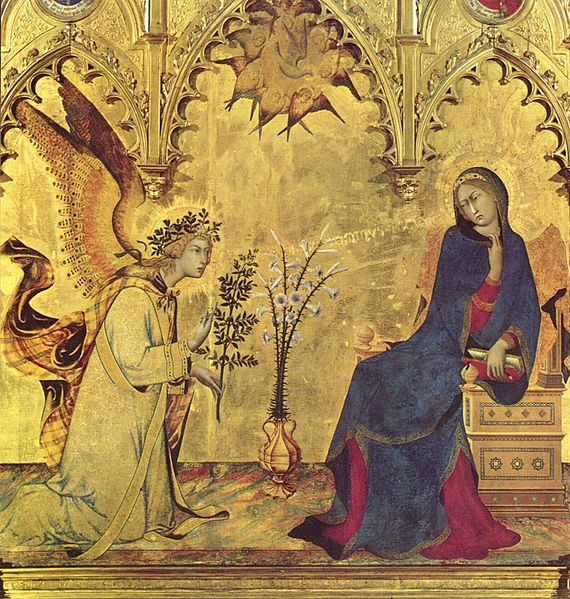

In this painting the train is crossing a bridge, people are seen sitting in open wagons, steam billows from the funnel, we can see a rowing boat on the river, someone holds up an umbrella, the sky is filled with swirling rain clouds. I cannot see it, the copy is too small, but there is in the lower right hand corner a hare, maybe a comment on the times, trains were ‘destroying the sublime elements of nature’ said one critic. Technology perhaps was feared as progressing too fast.

Turner was a British Romantic painter, his work is full of light ‘to whom a cosmic vision was more significant than a precise observation of reality. The world was merely an alibi for his canvasses where forms all but dissolve.’ Form, definition and photographic truth were abandoned,’ each particle of matter is part of a whole that is in a constant state of change’ I particularly like that phrase! His work would influence future painters, Impressionists such as Pissaro and Monet.

Turner was elderly and sick in 1844, he carried on working, his life had always lacked comfort, he took little interest in his dress and could be miserly at times, at others very generous, especially to young striving painters, he had an affection for birds and animals which softened his grumpy character. He held no religious or supernatural beliefs. He had loyal friends like Ruskin but also many critics, Ruskin admired his work in articles he published.

During his life he constantly travelled in England, Scotland and to Europe, he appreciated the light in Venice, always sketching and painting, he also visited other areas of Italy, France and Switzerland, forever searching for subjects. The Tate Gallery holds a collection of his watercolours. His memories of light, colour and atmosphere were not dimmed by his ill health when this painting was created.

link. en.wickipedia.org/wik/Rain_Steam_and_Speed