On the news recently I heard discussed the growing number of families who have to rely on food banks to supplement their meals, I was thinking about the next painting blog at this Christmas time and thought I would discuss the subject of an early painting by Vincent Van Gogh where peasants are seen eating a meal of potatoes.

Van Gogh was born in Neunen, the Netherlands, his father was a Calvanist minister and his mother has been described as a moody artist. Many of us will have heard of the difficulties Vincent had throughout his short life dealing with epilepsy, depression and his eventual suicide, I was surprised to learn that in the ten years he spent painting he created nearly nine hundred oil paintings and over a thousand water colours. Originally he wished to follow in his father’s footsteps but he was rejected as unsuitable on two occasions and decided to become an artist in 1880. In 1882 Van Gogh moved to Dreuthe and led a nomadic life, he studied Japanese art and Eastern philosophy, he wrote in ‘my own work, I am risking my life for it’, he wrote extensively about his work. He returned to Neunen in the north of Holland where he painted The Potato Eaters in 1885, the work is considered to be one of his earliest master pieces, he made several versions and preparatory sketches, working on the composition, this is his only group painting, he hoped the painting would promote his career, unfortunately not until after his death was it seen for what it is. Van Gogh felt very close to the peasants, he saw them as hard working and honest people who tilled the ground, planted and lifted the potatoes they were eating, he was also poor and struggling in his own way. The main character has her back to us, there are four women and a man, they may be related, who are sitting around a square table with rough edges on which is placed a large dish of potatoes, their faces are lit by the low- hanging lamp but the rest of the room is dark and cramped, we can see the rafters, a supporting wall which juts into the room and a picture on the wall, no light seems to be coming in the window at the back of the room. The characters are rather ugly and their hands are gnarled portraying the life of manual labourers.

who are sitting around a square table with rough edges on which is placed a large dish of potatoes, their faces are lit by the low- hanging lamp but the rest of the room is dark and cramped, we can see the rafters, a supporting wall which juts into the room and a picture on the wall, no light seems to be coming in the window at the back of the room. The characters are rather ugly and their hands are gnarled portraying the life of manual labourers.

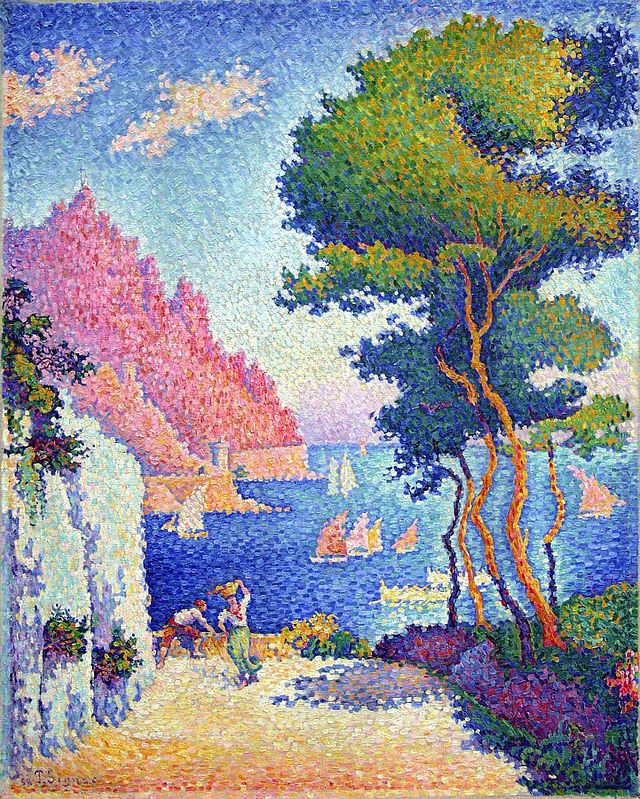

Van Gogh knew the work of the Impressionists but he was more influenced by the Hague school, his brush strokes were long and bold, in the room the colours are muted, black, dark green and brown, not until he moved to the sunshine of the south of France would his palette be more colourful, the bright yellows of his many sunflower paintings or the violets of irises, the reds and greens in his scenes and portraits, he made several self portraits of great intensity and insight.

Van Gogh hoped to set up a group of like minded artists and rented a house in Arles, he invited the painter Paul Gaugin to share it with him but they quarrelled and Gaugin left. Van Gogh become increasingly ill, his younger brother Theo with whom he remained close exchanged many letters, Vincent’s were filled with his theories and plans for paintings and his emotional state of mind, which he attempted to portray in his work, Theo arranged for him to live in a hospital in Auvers under the care of Doctor Gachet, he was given two rooms so that one he could use as his studio, he would set off to paint in the country side each day and return to the hospital in the evening, until his suicide. Van Gogh did not know how much his work would later be admired, he failed to make a living from his work.

I wish you all a happy Christmas.

Image from wikipedia.