On our recent summer retreat at Anybody’s Barn, I introduced an evening activity of drawing our own mandalas. This is a practice I experienced first in the Triratna Buddhist movement, but well worthy of wider adoption. There was some initial resistance, but everyone involved seems to have then found it a rewarding exercise, enabling them to reflect synthetically on the various factors supporting integration in their own lives or holding them back. It’s that process of reflection that’s valuable about it, rather than producing a work of art, but using visual symbols rather than words can also help to open up new perspectives.

What is a mandala? The terms derives from the Sanskrit word for ‘circle’, and mandalas are circular diagrams in which the spatial alignment of symbols in relation both to each other and to the centre can represent their relationship to an integrative process. The traditional Buddhist interpretation of mandalas is to see them as diagrams of enlightenment: but just by breaking down ‘enlightenment’ spatially one is already beginning to see it as an incremental process, a journey towards the centre, in which one may make asymmetrical progress. It’s for that reason that when Jung encountered mandalas he immediately identified them with excitement as diagrams of integration – a universal psychological process rather than one dependent on particular absolute Buddhist concepts. He found mandalas in many other cultural contexts, as well as in his dreams and in the dreams of his patients. Unfortunately, as with most such symbols, you’ll also find mandalas absolutised as symbols of cosmic order of some kind. The Wikipedia page on mandalas even starts off by saying they are symbols of the universe! But they most usefully represent our experience, not claims about ultimate reality.

It struck me recently that Jung’s adoption of mandalas as universal symbols, even though they were first identified explicitly in Buddhist culture, is a good analogy for the Middle Way. Jung used the idea of the Middle Way independently long before he engaged with Buddhism (see this earlier blog), but in a similar universal way to reflect a general human psychological process. If Buddhists have no problem with the idea that mandalas are universal, there seems no reason why they should not also accept the Middle Way as universal on a similar basis. Just as mandalas should not be defined in restrictive ways that prevent us from recognising the similarity of mandala forms across cultures, the Middle Way should also not be defined in restrictively Buddhist ways that prevent us recognising the absolutisations that may impede us in a variety of human situations rather than only those that applied at the time of the Buddha.

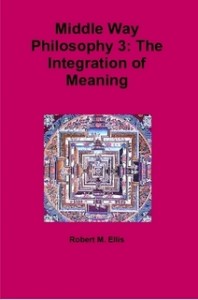

The integration depicted in a mandala is what I would call an integration of meaning: that is, that it depicts symbols that can be mutually recognised and synthesised in terms of a common understanding, even if they appear to be opposed. Of course that integration of meaning can also provide us with inspiration for an integration of belief: that is, we can reflect on the potential compatibility of some aspects of apparently opposed beliefs associated with the symbols. But a mandala itself doesn’t tell us how to reframe our understanding of opposed beliefs so that we can integrate them : it merely provides inspiration for doing so. The way in which mandalas can depict integration of meaning is the reason I used a mandala on the cover of my book Middle Way Philosophy 3: The Integration of Meaning.

Of course that integration of meaning can also provide us with inspiration for an integration of belief: that is, we can reflect on the potential compatibility of some aspects of apparently opposed beliefs associated with the symbols. But a mandala itself doesn’t tell us how to reframe our understanding of opposed beliefs so that we can integrate them : it merely provides inspiration for doing so. The way in which mandalas can depict integration of meaning is the reason I used a mandala on the cover of my book Middle Way Philosophy 3: The Integration of Meaning.

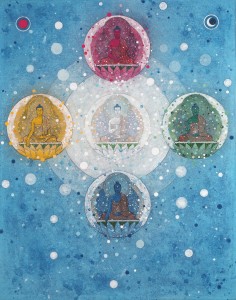

One of my favourite Buddhist mandalas is the Five Buddha mandala, because this depicts five symbolic Buddhas that represent different types of wisdom. These types of wisdom are in constant tension with each other. For example, the Blue Buddha, Akshobhya, represents non-discriminating or mirror-like wisdom according to which all  beliefs are ultimately empty (because none can be absolutely justified). On the opposite side of the mandala to Akshobhya, though, is the Red Buddha Amitabha, who represents discriminating wisdom as well as compassion. At the same time as recognising the lack of ultimate justification for our beliefs we need to recognise that as embodied beings we can adopt provisional beliefs about our specific environment, and indeed have particular loyalties to the people we know in our embodied experience. Thus we do not need to flip between absolute scepticism and particular loyalty: we can integrate those perspectives, and the White Buddha Vairocana can represent that integration in the middle. Similarly, the Green Buddha Amoghasiddhi represents the wisdom of success, as opposed to the wisdom of sameness in the Yellow Buddha Ratnasambhava. On the one hand we are actually attached to particular desires and wish to be successful in achieving them, whilst on the other we can recognise that from a different perspective, those desires and their fulfilment may not be significant and may be generously renounced for a wider perspective. The White Buddha can simultaneously represent the integration of these perspectives. That’s only a brief taste of the richness of the Five Buddha mandala. Vessantara’s Meeting the Buddhas is a useful guide to this symbolism.

beliefs are ultimately empty (because none can be absolutely justified). On the opposite side of the mandala to Akshobhya, though, is the Red Buddha Amitabha, who represents discriminating wisdom as well as compassion. At the same time as recognising the lack of ultimate justification for our beliefs we need to recognise that as embodied beings we can adopt provisional beliefs about our specific environment, and indeed have particular loyalties to the people we know in our embodied experience. Thus we do not need to flip between absolute scepticism and particular loyalty: we can integrate those perspectives, and the White Buddha Vairocana can represent that integration in the middle. Similarly, the Green Buddha Amoghasiddhi represents the wisdom of success, as opposed to the wisdom of sameness in the Yellow Buddha Ratnasambhava. On the one hand we are actually attached to particular desires and wish to be successful in achieving them, whilst on the other we can recognise that from a different perspective, those desires and their fulfilment may not be significant and may be generously renounced for a wider perspective. The White Buddha can simultaneously represent the integration of these perspectives. That’s only a brief taste of the richness of the Five Buddha mandala. Vessantara’s Meeting the Buddhas is a useful guide to this symbolism.

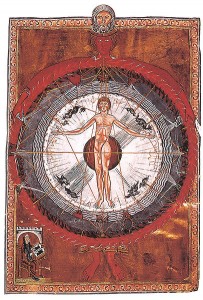

The Buddhist tradition has developed mandala symbolism in the most extraordinary ways, including not just paintings but also in a multitude of other forms: ageless monuments (at Borobodur and Mandalay – which is named after mandala) at one extreme and temporary sand mandalas at the other. Beyond Buddhism, mandalas are also widely used in Hinduism. In Christianity, you can find mandala forms in Celtic crosses and rose windows.  Pictured here is a Christian mandala from Hildegard of Bingen’s fascinating mystical writings, which are accompanied by a number of illustrations as she was an artist as well as a writer. Interestingly here it is the human body that is the focus of integration at the centre of the mandala, and the depiction of God (who appears to be both males and female) encompasses the mandala as a whole rather than only its centre. The stretched figure, representing the universal man, is reminiscent of Christ on the cross, which is used at the centre of a number of Christian mandalas. Jung remarked that Christ being crucified between two thieves itself forms a mandala, especially as one of the thieves is traditionally said to have repented and responded positively to Christ whilst the other reviled him. There is thus a pattern of opposites in the two thieves to be symbolically integrated in Christ, who can represent the role of the acceptance of suffering in widening our perspectives to accept new conditions.

Pictured here is a Christian mandala from Hildegard of Bingen’s fascinating mystical writings, which are accompanied by a number of illustrations as she was an artist as well as a writer. Interestingly here it is the human body that is the focus of integration at the centre of the mandala, and the depiction of God (who appears to be both males and female) encompasses the mandala as a whole rather than only its centre. The stretched figure, representing the universal man, is reminiscent of Christ on the cross, which is used at the centre of a number of Christian mandalas. Jung remarked that Christ being crucified between two thieves itself forms a mandala, especially as one of the thieves is traditionally said to have repented and responded positively to Christ whilst the other reviled him. There is thus a pattern of opposites in the two thieves to be symbolically integrated in Christ, who can represent the role of the acceptance of suffering in widening our perspectives to accept new conditions.

In the end, it doesn’t matter so much what tradition you approach mandalas through so much as that you make integrative use of it. Whatever the traditional role for such diagrams, they are not ends in themselves and do not usefully represent any kind of ultimate truth. Rather they represent a process by which you yourself can be inspired to reframe your experience. Around the outside of the mandala I drew on the recent retreat were to be found Facebook, bathroom cleaning, negative events in world politics, and the temptations of cake, all of which represent things that could be integrated, but are quite hard to deal with! Nothing is too mundane to be included and ultimately be open to integration.

Pictures: Five Buddha Mandala by Aloka, used on the cover of ‘Middle Way Philosophy 4: the Integration of Belief’ with the kind permission of Vaddhaka; Hildegard of Bingen picture from Liber Divinorum Operum (Wikimedia).