There is no podcast this week because Barry is away. Instead, here is the latest instalment of the series of talks and discussions recorded on last year’s retreat. This one is of great practical importance, as it discusses how we can make practical moral judgements justified by the Middle Way, and includes example issues like cannibalism, vegetarianism, euthanasia and abortion. If you’d like the opportunity to discuss this live, do sign up for the online discussion group at 6pm on Sun 30th March, when we’ll be discussing ethics. In the meantime there is also the comment function.

Category Archives: Ethics

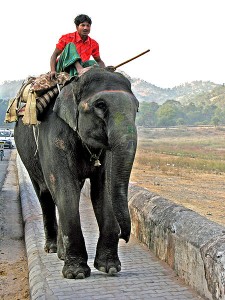

The rider and the elephant

Can we actually change our moral responses? Much debate about moral issues is fruitless because, however well-justified the reasons given for one position or another, they make no difference to our position. Rather than changing our position in response to strong evidence or argument seen overall, we tend to focus on minor weaknesses in views we intuitively oppose (or minor strengths in views we support) and blow them out of proportion. I’ve recently been reading Jonathan Haidt, who encapsulates this situation in the image of the rider and the elephant.  The rider thinks he’s in charge, but most of the time he’s just pretending to direct an elephant that is going where it wants to go. He gives lots of psychological evidence for the extent to which we rationalise things we’ve already judged, rather than making decisions on the basis of reasoning. This is the whole field of cognitive bias. For example, people experiencing a bad smell are more likely to make negative judgements, and judges grant fewer parole applications when they’re tired in the afternoon than they do when they’re fresh in the morning.

The rider thinks he’s in charge, but most of the time he’s just pretending to direct an elephant that is going where it wants to go. He gives lots of psychological evidence for the extent to which we rationalise things we’ve already judged, rather than making decisions on the basis of reasoning. This is the whole field of cognitive bias. For example, people experiencing a bad smell are more likely to make negative judgements, and judges grant fewer parole applications when they’re tired in the afternoon than they do when they’re fresh in the morning.

However, too many people draw a cheap moral determinism out of this. That’s a determinism expressed by Hume in his famous line “reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” Fortunately Haidt, who’s a professor of moral psychology at the University of Virginia, recognises that Hume’s position is over-stated, and that it is based on a simplistic false dichotomy between reason and emotion. Just because the rider tends to over-estimate his influence on the elephant, doesn’t mean he has no influence at all. Rather, someone controlling a beast with as much bulk and momentum as an elephant needs to develop skills to encourage it in one direction rather than another, and to set up the conditions that will encourage it to go one way rather than another rather than just telling it and expecting it to obey instantaneously. Nor are the rider and the elephant to be equated to “reason” and “emotion”: each uses reasoning, and each has motives and starting points for reasoning, making a complex mixture of the two in both rider and elephant. The elephant would be better described as an elephant of intuition and the rider as conscious awareness.

Haidt, like most scientific or academic commentators on this kind of issue, also makes certain questionable assumptions. One of these is that of the essential unity of the rider and of the elephant (particularly the elephant). If it was true that the elephant definitely wanted to do one thing, and the rider another, it would be pretty much impossible to steer the elephant in any sense. But this is an over-simplification of the physical intuitions we get from our bodies. We may intuitively judge one way, but there is also an intuitive sympathy to some extent for the opposing approach. Perhaps we should not think of the rider so much as astride one elephant, as leading a herd of them. To lead the herd you find the elephant who is pre-disposed to act in the most objective way, encourage it, and (because elephants are herd animals) the rest are likely to follow.

That’s where integrative practice comes in. In the over-specialised world of academia, it seems to often to be the case that those engaged in crucial and ground-breaking research in psychology (such as, say, Daniel Kahneman and Jonathan Haidt) have evidently never experienced meditation, and completely ignore the potential of meditation and of other integrative practices to modify our responses. There are, of course, other academics investigating meditation, but these usually show little interest in ethics or judgement. Cheap determinism seems to rule, for the most part, because over-specialised people don’t join up the evidence in different quarters, and the incentive system could hardly be better geared to discourage synthetic thinking.

In meditation, one can become more aware of that variety of possible responses. Meditation is, in effect, a close scrutiny of the elephant on the part of the rider, from a sympathetic inside viewpoint. The better he knows the elephant, the more he can skilfully manage it. He can rein in the elephant a little so it has more time to listen to the other members of the herd. He can make it more aware of ambiguity using humour, art or poetry. He can give the elephant a wider range of options by educating its sensibility. He can help the elephant become more aware of the rider, and cultivate its sympathy for the rider.

That doesn’t mean that the elephant will ever cease to go where it wants to go. The question is just what it means to ‘want’. Wanting is never simple. We have lots of wants, and it is the integration of those wants that helps us steer the elephant in a more acceptable direction – indeed that helps us see what that better direction is. The rider really needs the elephant, and no merely abstract morality can be justified that does not take that elephant into account.

Picture: Rider and elephant by Dennis Jarvis (Wikimedia Commons)

Meditation 4: Meditate till the neighbours complain….

“You migglers seem a rowdy crowd!

You argue, cuss, and laugh out loud,

You seldom chant or bend a knee

Before a gilded effigy!”

Thus begins the three stanza jingle I composed as part of a joint poetry spree with other participants at an early stage in the development of the society. Although I experienced the ‘spree’ as fun, I had an inkling that it was also a serious exercise, intended as a marker for the direction of Middle Way Philosophy as real-life practice, rather than as a distraction from real life (as traditional Buddhism sometimes seemed); or as an intellectual take on life without actually engaging with it, as some Buddhist writers and teachers convey.

Writing of poetry as an integrative tool, Robert M Ellis* suggests that to write it is the best way to use it, especially if the writer can delight in her creation, which she produces for its own sake, and perhaps for the sake of others, acknowledging her imperfect motivations in doing so. My own motives are still under examination, and as I read and re-read the words I strung together then with pleasure and a real sense of accomplishment and pride, they are beginning to reveal more layers of meaning than I might have imagined at the outset, and a presentiment of more to come. Not all my notions are comfortable ones.

In developing the verses I envisioned and my lines suggested a slightly taken-aback observer of a group of migglers, plucking up courage to be forthright in his opinion of what they were about, speaking to them directly, and with a hint of rebuke. “A rowdy crowd”, seemingly. At least that leaves room for a counter-argument, but not much. The evidence in support of that judgement? People arguing, ‘cussing’ and laughing out loud. Immoderate and uproarious, in other words. Irreverent too, and individualistic to the point of being “bolshie”. Perhaps untroubled by the idea of breaching etiquette, or even of giving offence.

One can see plainly that in this verse I am setting out my own stall, or planting my own flag on the small mound of migglism, and that the poem is a rallying cry, summoning allies to my cause: to dissent, to discrepancy, to contrariness, to cussedness, to iconoclasm, and even to ridicule, or at least to the ridiculous, the absurd, and the plain silly. For some of these give me delight, and I enjoy the sense of delight that comes with the freedom to dissent, to be silly, and I love to share my delight with others, and have them share theirs with me, and with their others. Which you do!

In my several years of association with Buddhism, and my contact with Buddhists, it hasn’t been my experience that delight has figured at all strongly, and possibly not at all. On the contrary, there’s been hardly any fun in it, let alone delight, and my overall impression has been of unremitting dreariness, with an apparent striving after piety, contrived seriousness, and apologetic self-effacement. Some of this may well be authentic, but it gets lost (or so it seems to me) in an ocean of other-worldliness, with a fierce competitive edge (like a basking shark). Do you know any really funny Buddhist jokes?

I’ve always wondered why meditation has been so drearily characterised in the literature, and by some teachers. On the occasions when I wonder if I’m taking an extreme view, I recall an incident in a meditation hall when I witnessed a senior monk roughly push a meditating novice off his cushion because he was sitting so close the senior’s exalted seat that it incommoded the latter’s stately progress, hands folded and eyes downcast, towards it.

I think I understand meditation to be an important ‘limb’ of the three-limbed practice that Middle Way Philosophy proposes, a practice conducive to the incremental integration of desire, meaning and belief, and a means to dogma-free, non-authoritarian, and ethical life. And I conceive of the possibility of – and maybe the necessity for – a wide range of meditative practices in which freedom, creativity, enjoyment, non-conformity, fun, delight and ecstasy are vital constituents; and can be happily shared, experimented with, joked about, laughed at, and giggled over. Practices that bring a flush to the cheeks, a glow to the eyes, a smile to the face and beyond it, and even an occasional complaint from the neighbours.

I’m going to make my this starting point, and I want to enlist others to the cause. So how about it? All together now!

* Ellis R M (2013) Middle Way Philosophy 3: The Integration of Meaning, Lulu (Publisher) Carolina, USA.

The Current Confusion about Ethics

This enhanced audio, the first of a series about ethics recorded on last summer’s retreat, argues that although we are probably more ethical than we used to be on the whole, we are also confused about how to justify ethical beliefs. In the absence of metaphysics to  justify ethics we haven’t found an experiential way of justifying it instead, but rather tend to substitute other ways of talking that cloak ethics using law, popular psychology, professionalism, political correctness etc. We might be much less confused if we started by facing up to ethics as such, and the need to justify it as ethics.

justify ethics we haven’t found an experiential way of justifying it instead, but rather tend to substitute other ways of talking that cloak ethics using law, popular psychology, professionalism, political correctness etc. We might be much less confused if we started by facing up to ethics as such, and the need to justify it as ethics.

The later parts of the series will go on to explain how ethics can be justified in Middle Way terms without appealing to metaphysics.

Internet communication

So far on this website, we’ve got by without any of the rules of discussion that most blogs, forums, etc. seem to need. I was keen not to introduce them unnecessarily, and indeed, the discussion on the website itself so far has been almost without exception thoughtful and civilised. However, I’ve just had a discussion on our Facebook page that left me feeling decidedly bruised: one that, with hindsight, I should probably have avoided getting drawn into, since some of the warning signs were there quite early on. By the end of it, my contribution was being dismissed as ‘utter gibberish’, and in the final post from the other person (which I have deleted, because it was beyond the pale in my judgement) it was seriously being argued that this kind of language was OK because it wasn’t as bad as something stronger such as ‘bullshit’, and that my motives for objecting to it must be to create a distraction from losing the argument.

This has left me thinking that we probably need to be better prepared for the high likelihood of more people communicating in this kind of way in the future – with an agreed set of bottom line rules that we can point to and be clear about. The problem is not the worst and most obvious kind of internet offender – the spammer or the troll. These people get excluded early on, and usually don’t get as far as posting comments. The problem is the person who may have serious points that are worth listening to – but unfortunately combines that with wanting to ‘win’, or prove the superiority of their group or ideology, much more than having a genuine interest in getting nearer to the truth of the matter. Personally, I am keen to listen to challenges, learn from them and respond to them. However, I’m not keen to be bullied by people who want to take advantage of my willingness to listen to them, and who do not reciprocate with any openness or flexibility of their own. I’m even less keen to see others treated in that way on this site or on our Facebook page – others who might potentially be more vulnerable that I. The unreflective contributor who wants to win (overwhelmingly male) tends to interpret every concession as a weakness to be exploited, and then lunge for the final kill, to complete the triumph on behalf of their tribe. I don’t think we should underestimate how nasty and disruptive such people can be.

It seems to me that rules are probably the best and most effective way of dealing with such people. There are some that do not want to engage in internet discussion at all, because they perceive it as being dominated by this sort of interaction. But internet discussion can be rich and rewarding. It can certainly challenge us in ways we would not otherwise have been challenged, in communication with people we would never have communicated with before the internet. In my view, those who don’t want to engage in it are missing something of potential value. The Middle Way here seems to be to try to provide a safe and moderated environment where even those with limited confidence in internet discussion can engage in it without fear of being bullied in any way. The basic problem with the internet is that people generally only engage with it using their left brains, with all the contextual signals of face-to-face communication (that would come through the right brain) missing. So, to make up for this, we need to bring in additional prompts for the left brain to connect with the wider awareness of the right.

So, I’m going to suggest a draft set of rules that I think would be in harmony with the Middle Way approach and the values of the society. I’ve tried to keep these as simple as possible and got them down to nine. I’d like these rules to apply to this website, to our Facebook page, and to a forum if we ever manage to get one going. I’d like your feedback on these.

1. Try to be aware of both yourself and the recipient of your communication as embodied people.

2. Every embodied person has experiences to communicate that are worth crediting, even if you think their interpretation of them is mistaken.

3. Do not make assumptions about the motives of a person you don’t otherwise know based only on text you have read on the internet. Most of these assumptions are likely to be deluded projections.

4. Do not use unnecessarily emotive language of any kind to express disagreement. There are always more neutral-sounding alternatives that make the same point. For example, don’t write “That’s nonsense” but “I disagree with that”.

5. Take responsibility for your own judgements, even if they are influenced by others. Offer justifications for your claims, and recognise your assumptions if they are pointed out.

6. Make your judgements incremental rather than absolute, unless you are pointing out an absolute claim: e.g. not “that’s completely wrong” but “I can’t see much support for that” or “that view seems to be a metaphysical claim beyond experience”.

7. Do not use appeals to an authoritative source – e.g. tradition, scripture, science, popularity, convention etc. to try to prove or disprove any claim. At best these kinds of sources may increase or decrease credibility, sometimes strongly but not absolutely.

8. Apply the principle of charity in interpreting ambiguous statements positively. E.g. If a group of people is criticised that might be interpreted as including you, do not identify with that group and assume that the criticism is directed at you.

9. Try to bring about a consensus in which those who disagree find some common ground, or at least clarify what they disagree about. Do not try to win.

There are dangers with rules: obviously that we can get too tied to them and become bureaucratic. The very introduction of a rule changes the tone of things in a way I rather regret, which is why I wanted to put them off as long as possible. However, I think they have to be rules rather than just guidelines, because they may need to be applied to unsympathetic strangers to the site who object to being moderated. Like all rules, they seem to be an unfortunate necessity

Do you agree? Do we need rules? Are these the right sorts of rules?