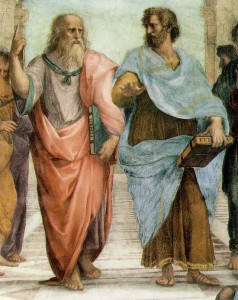

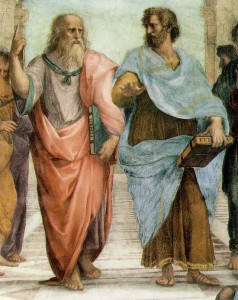

In Raphael’s famous picture ‘The School of Athens’, the highlighted two standing philosophers in the middle are obviously intended to be the most important. They are Plato and Aristotle. Plato is pointing upwards, symbolising rationalism and its appeal to transcendent reason, but Aristotle is pointing downwards towards the Earth, to symbolise the empirical appeal to experience and the earth. The Buddha is also sometimes depicted touching the ground, in a way that could be taken to symbolise the ‘groundedness’ of his view of things.

In Raphael’s famous picture ‘The School of Athens’, the highlighted two standing philosophers in the middle are obviously intended to be the most important. They are Plato and Aristotle. Plato is pointing upwards, symbolising rationalism and its appeal to transcendent reason, but Aristotle is pointing downwards towards the Earth, to symbolise the empirical appeal to experience and the earth. The Buddha is also sometimes depicted touching the ground, in a way that could be taken to symbolise the ‘groundedness’ of his view of things.

The Buddha’s relationship to experience can be seen as the basis of his Middle Way, avoiding either positive or negative metaphysical claims. But can we say the same for Aristotle? The resemblances, at first sight, are striking. Not only is Aristotle often regarded as the first empiricist in the Western tradition (and also the founder of Western science, the first to seriously use observation to support his claims), but he also taught a virtue ethics, with the famous Golden Mean as a guide to how we could identify a virtuous quality. A practical virtue, he said, is found mid-way between the excess and the deficiency of a quality. For example, courage (a true virtue in his view) is found mid-way between cowardice (the deficiency of courageous quality) and foolhardiness (its excess). Is this an ancient Greek version of the Middle Way?

Sadly, not quite. There is much to admire in Aristotle. He was a multi-talented figure who took an interest in everything from biology to poetry. He learnt from his master Plato and went beyond him. His Ethics, and particularly the chapter on friendship, are of particular interest today. Aristotle can be a great source of inspiration, but he should certainly not be assumed wholesale to have hit the Middle Way. Nor should the Middle Way be described as ‘Aristotelian’. For there are still some basic ways in which Aristotle remains in a set of metaphysical assumptions that might take us off in a different direction.

Aristotle did challenge the metaphysics of Plato, but he also developed his own metaphysics. Rather than basing this on absolute reason like Plato, he made the assumption that we could observe the truth about the world through the senses. Where Plato evidently believed that the Forms (ultimate essences) lay in reason alone beyond the world, Aristotle believed that they lay in each individual thing in the world. Through observation we could work out the essence of a thing, and thus its true purpose. He thus assumed that the world was formatted in a way that would allow scientists to understand it correctly, and that observation of human beings could also show us their true nature and purpose. ‘Man’ he famously wrote, ‘is a rational animal’: meaning that what is essential and distinctive about humans is their rationality. Our true purpose, he believed, can thus be fulfilled by developing that rationality.

The Golden Mean, then, needs to be understood in its context. It’s not a method for taking into account the limitations of our understanding in the whole of experience, as I take the Middle Way to be. Rather it is Aristotle’s account of how he thinks humans can be good and fulfil their true purpose. He believes that we should develop our rational virtues, which help us judge whatever we meet, but we should also develop our practical virtues , which are gained through practice and involve a balance between excess and deficiency. Instead of using the Middle Way to judge both facts and values, Aristotle treats each differently. The facts, he thinks, are known by examining the world and understanding the essential truths about each thing and its purpose. Right values, however, are developed by applying what we have learnt, even though doing that requires practice as well as theory. Even though he has an attractive ethics that emphasises balance and has a strong practical aspect, Aristotle was a naturalist.

Aristotle’s general approach can thus easily be used to justify practices that are believed to have been observed in the world, even though they’re obviously the product of the assumptions made by the observers. That’s why his ideas are still invoked by the Catholic Church today (via their interpretation by St Thomas Aquinas) to support the belief that sex is ‘naturally’ for procreation, and that to use it merely for pleasure is a sin. One can, of course, observe the link between sex and procreation, but the belief that procreation thereby becomes the essential purpose of sex, and then that to do otherwise is wrong, involves a whole pile of dogmatic assumptions.

To get closer to the heart of the Middle Way in ancient Greek philosophy, I think, we must look instead to Aristotle’s near-contemporary Pyrrho. I will discuss Pyrrho in more detail some other time, but the key point here is that Pyrrho was able to pursue sceptical arguments against the supposed ‘truths’ that Aristotelians thought they were able to observe. Sceptical arguments show that there can be no such known ‘truths’, only provisional beliefs. Pointing us downwards towards our experience is a step in the right direction, but empiricism, too, can be dogmatic. It’s only if we can hold our empirical beliefs with genuine provisionality that we start to get closer to the Middle Way.

Link to index of ‘Middle Way Thinkers’ blogs