New Review of ‘The Ethics of Uncertainty’

New Review of ‘The Ethics of Uncertainty’

A new review of a neglected book, that explores the Middle Way in Christianity through its ethics.

New Review of ‘The Ethics of Uncertainty’

New Review of ‘The Ethics of Uncertainty’A new review of a neglected book, that explores the Middle Way in Christianity through its ethics.

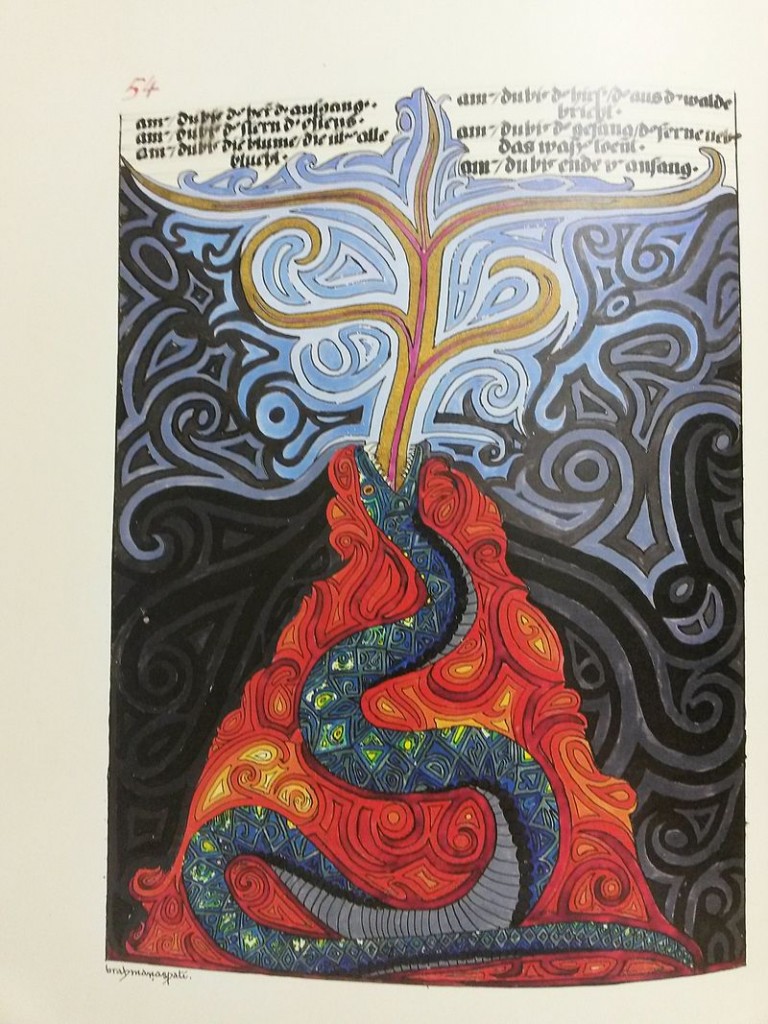

He sees the tree of life, whose roots reach into Hell and whose top touches Heaven. He also no longer knows differences: who is right? What is holy? What is genuine? What is good? What is correct? He knows only one difference: the difference between above and below. For he sees that the tree of life grows from below to above, and that it has its crown at the top, clearly differentiated from the roots. To him this is unquestionable. Hence he knows the way to salvation.

To unlearn all distinctions save that concerning direction is part of your salvation. Hence you free yourself of the old curse of the knowledge of good and evil. Because you separated good from evil according to your best appraisal and aspired only to the good and denied the evil that you committed nevertheless and failed to accept, your roots no longer suckled the dark nourishment of the depths and your tree became sick and withered. (p.359-360)

Here Jung gives what for me is a brilliant summary of the basis of Middle Way ethics. A frequent theme of the Red Book is that of recognising the depths and integrating what we take to be evil. In this sense we go ‘beyond good and evil’ (to use the phrase also used by Nietzsche in his book of that name). To go beyond good and evil sounds to many like relativism or nihilism, leaving us adrift without any justifiable values. But what is required instead is a recasting of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ that takes into account our degree of ignorance, recognising that much of what we reject as ‘evil’ is bound interdependently with what we accept as ‘good’. Instead of rejecting good and evil altogether, we need to understand a more genuine or integrated form of ‘good’ as lying beyond our current understanding, and ‘evil’ only as that which prevents or disrupts integration.

If we focus only on the uncertainty in our current understanding of good and evil, and take that uncertainty to be a negative thing, we will miss the positive implications that Jung brings out in his image of the Tree of Life. The crown of the tree, he tells us, is clearly differentiable from the roots. This would be the case only in terms of experience, not conceptual analysis, because the difference between the crown and the roots is incremental. Nevertheless integrative progress is part of our experience. There may be some adults who have got irredeemably stuck in one set of rigid beliefs and thus stopped growing, but this can hardly ever be the case for children: if we compare ourselves as toddlers and as adults, we have all made some sort of progress, addressing conditions better than we did then. The crown is thus differentiable from the roots, even though there is no absolute point of change in between.

It is also telling that Jung writes “To unlearn all distinctions save that concerning direction.” The new good is a direction, not an absolute, because we do not have full understanding of it and cannot pin it down just by intellectual analysis. Even God as encountered in our experience (as discussed in the previous blog) is a symbol for a direction: the direction of integration in which we only get better, not ultimately good. That also implies that we cannot deduce that direction from any account of an ultimate goal, such as the Buddhist Nirvana. There can be no final goal, for such a goal would be irrelevant to us. As Jung writes in another place:

Not that I know anything about what my distant goal might be. I see blue horizons before me: they suffice as a goal. (p. 276-7)

The roots of the Tree of Life are nourished by every aspect of our organic experience, whether by ‘good’ or ‘evil’ as normally understood. This point is also put very graphically later in the text, where Jung shows his utter disgust with the devil at the same time as a reluctant recognition that the devil is necessary. He describes the devil as having a ‘golden seed’.

He emerged from the lump of manure in which the Gods had secured their eggs. I would like to kick the garbage away from me, if the golden seed were not in the vile heart of the misshapen form. (p.424)

This passage tells us something about how difficult it is in practice to face up to the integration of the Shadow. Think of everything you most loathe: paedophiles, Daesh, Donald Trump. Then try to get your head around the way that they have gained control of things that are necessary for you. To start with, your representations of such figures are yours – take responsibility for them. It’s your inner Donald Trump that you hate, not the one out there. The energy that you’re putting into hating your inner Donald Trump is your energy: don’t let him steal it from you. You need to reclaim it from Donald Trump and put it to better use.

But if we are to integrate ‘evil’ without falling into relativism, there also still needs to be a genuine evil that we recognise. Such evil consists in whatever stops the Tree of Life from growing, whatever interferes with the integrative process. That’s where I would draw conclusions that go beyond Jung, but to me seem to be implied by Jung’s insights. That is that what blocks the integrative process is absolutisation. Absolutisation is found in our rigid beliefs, whether positive or negative, which prevents us from responding to new experience and benefitting from it. A given belief is only a part of us, so no person is wholly evil, nor is any tradition or organisation. However, metaphysical beliefs poison the Tree of Life.

This new account of evil is not wholly distinct from the old evil. I think it can be shown how existing common conceptions of evil show the features of absolutisation, and I have explored this in a previous blog as well as in my book ‘Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief’ (section 3.n). Evil is associated with power, despotism, egoism, greed, cruelty, obsession, manipulativeness, defensiveness, rigidity, impatience, pride, short-termism, literalism, despair, emotional impoverishment, and false emotion. Some of these qualities are found in Jung’s experience of evil as found in the Red Book, such as Jung’s encounter with the mocking and sardonic ‘Red One’. All of these kinds of qualities can also be associated with narrow over-dominance of the left hemisphere of the brain when we make judgements.

So it’s not that we have been wrong in our instincts about what sorts of qualities are evil – the problem is only in how we apply those instincts. We have assumed evil to be something external to us, consisting in whole people, objects or institutions, when instead it is to be found in the beliefs that poison the Tree of Life. We need to learn to separate the beliefs from the people: to stop projecting the Shadow onto others, or onto external supernatural forces, and recognise it as an archetype in ourselves.

Another implication of the image of the Tree of Life is that its growth will happen regardless (as a result of life) if it is not interfered with. As long as the roots can get their nutriment without hindrance, we do not have to make the tree grow towards good. However, preventing the hindrance to the roots may take much more deliberate action. If someone were to try to pour poison on the roots we would have to actively stop them. That’s why I think we can’t take the process of integration for granted, but rather need to be on the alert and using our critical faculties to detect and avoid absolutisations. That’s why the practice of the Middle Way, the avoidance of absolutisations on both sides, is not just a matter of innocent effort. It also takes a degree of educated cunning. We cannot just tell those who want to absolutise that they are entitled to their opinion and leave it at that, but whenever we can do so fruitfully we need to contest, not them, but their opinion. Even if we fail to convince others, we need to free ourselves of the shackles of intrinsically rigid ways of thinking.

You should be able to cast everything from you, otherwise you are a slave, even if you are the slave of a God. Life is free and choose its own way. It is limited enough, so do not pile up more limitation. Hence I cut away everything confining. I stood here, and there lay the riddlesome multifariousness of the world. (p.378)

Previous blogs in this series:

Jung’s Red Book 1: The Jungian Middle Way

Jung’s Red Book 2: The God of experience

Picture: from Jung’s Red Book (Xabier CCSABY 4.0)

As a former Buddhist of about 20 years, I still have many Buddhist friends, and one of the most frequent things I disagree with them about (I hope, amicably) is karma. Karma is a complex and tricky subject, that is often misunderstood, so I often find that when I raise objections to it, people who have studied karma and know something about it tend to jump to the conclusion that I’m in one of those categories of misunderstanding. I think otherwise. I recognise (I think) all the common misunderstandings. I recognise a whole set of reasons why some people – Buddhists, Hindus, New Agey types, or whoever – believe that a belief in karma is a good thing, but I think they’re also missing the bigger reasons why it isn’t. Instead, the practice of the Middle Way should, I think, lead us to abandon belief in karma. This is going to be a difficult subject to encapsulate in the length of a blog, but I’m going to have a go.

First, let’s acknowledge and leave behind various misunderstandings of karma. Even in its most traditionalist Indian versions, karma does not mean ‘fate’. Instead, it literally means ‘action’, and is a contraction of ‘karma-vipaka’, the ripening of action. Karma thus means the effects of action, and those effects are only believed to be inevitable once you’ve done the actions. The original significance of karmic doctrines in both Hinduism and Buddhism was thus to help people take responsibility for their actions, avoiding fatalism. It needs to be noted that ‘action’ here includes mental as well as physical actions: even a thought is an action, though often a less significant one than a physical action. The insight to be found in karma doctrine is that our actions, including mere thoughts, do always have effects of some kind. However, karmic doctrine also asserts that these effects return to us in a proportionate way.

Another confusion around karma lies between retrospective and prospective ways of looking at it. Retrospective karma is when you notice a condition (e.g. a disability) and attribute it to an action in the past (e.g. you must have done something bad in the past to get that disability). The belief in retrospective karma involves the assumption that there are no other kinds of conditions at work (other than karma), such as genetics, to produce something like a disability. This kind of belief in karma – though still common – is pretty crass. However, when I suggest that belief in karma is unhelpful, I’m not only talking about retrospective karma. The prospective view of karma, where you assume that your actions will always lead to a proportionate result for you (even when you don’t know for sure which of the conditions that affect you are due to past karma) raises quite enough problems without needing to get into the retrospective version.

In the most common Hindu view of karma, an atman, or eternal self, receives the karmic effects of your past deeds. However, in Buddhism, belief in karma is combined with the anatman or ‘no-self’ doctrine (which is often interpreted as denial of a continuous self, but may more subtly be seen as agnosticism about it). If there is no self, though, who deserves the effects of past deeds? The person who receives the karmic effect is different from the person who performs the action, and thus the idea that karma has any moral significance, or that the person who receives the effect ‘deserves’ it, falls apart. A Buddhist text called the Questions of King Milinda tries to explain this by analogy to a mango and a mango tree: the person who planted the mango, it is argued, deserves the fruits of the ensuing mango tree, even though the mango is different from the tree. But what if someone else owned the land, a third watered and fertilised the young mango tree, and a fourth made the effort to pick the fruit? At best, then, the person who planted the mango might claim a small share! After many years of thinking about this problem, I can’t see this juxtaposition of Buddhist doctrines as anything other than thoroughly contradictory. What’s more, the contradiction is not somehow indicative of deeper wisdom – it’s more likely just an ineffectual attempt to patch up the relationship between incompatible beliefs in which people had developed vested interests.

The most basic problem with karma is that it requires a perfect system of just desert. Even if you don’t know when it is coming or how, karma requires that your action today will create corresponding effects in the future. But given that we are (as the Buddhist ‘no-self’ doctrine suggests) always changing, there is no way that we could perfectly ‘deserve’ those effects of actions done by someone different in the past. We can experience all sorts of effects of previous actions, yes, but the extent to which we benefit or suffer from them is unclear and inexact. If you say something unkind to Mr Smith today, he may get his own back tomorrow. If you fill in your tax return dishonestly, you may be tortured by pangs of conscience, and the revenue may catch up with you in future. Very often, indeed, people underestimate these kinds of moral effects. But the belief that they must be inevitable and morally proportionate is just dogma: experience gives us no grounds to assert such a thing.

Of course, it is the problem of what happens to karma that hasn’t obviously had its effects within a given person’s life that leads to the doctrine of rebirth. If your karma hasn’t paid you back in this life, the argument goes, then it will do so in another. Here we very clearly go beyond anything that can be supported through experience, and into the realm of speculation and dogma. I’m not going to go further into the question of rebirth here, because without karma, there is no particular reason to take it seriously. Karma is the more basic issue, and rebirth is just a big ad hoc defence of karma in the face of just one of the many ways the doctrine is inconsistent with experience.

One of the insights related to karma, especially in the Buddhist tradition, concerns the ways in which our states of mind contribute to its workings. Indeed, on some accounts (such as that of the Yogachara school), karma is entirely a matter of stored mental effects, and the reason we experience karmic effects of our previous actions is that our deeper minds themselves store and channel those effects. Could the supposed perfection of karmic effects be explained by their mental nature? Well, neuroscience makes clear the likelihood that any given judgement can contribute to the entrenchment of a mental habit. For example, if we get into the habit of drinking too much alcohol, the prospect of alcohol creates a feedback loop in the brain, in which synaptic tracks get increasingly more entrenched. We both develop a mental model in which alcohol will meet our needs, and reward the fulfilment of that model through the dopamine hits we get from receiving it. Is the belief in karma really an ancient insight into the way our brains work?

Well, no, because there’s a big difference between an entrenched habit and an inevitable effect. The significance of an entrenched synaptic track in the brain is that it makes it much more difficult to act differently. We have to exert effort, and use more glucose, to do something different like drinking an orange juice. However, there’s nothing inevitable about the effects of that track. We could conceivably just carry on making that effort to drink orange juice instead of alcohol, and the appeal of alcohol may very gradually fade as new alternative tracks are made. The habit may well lead to me feeling the ‘karmic effect’ of the negative effects of alcohol-craving in one way or another in the future, but if we are to take responsibility for our actions we also need to accept that it may not. Uncertainty is a much more basic condition than habit and its effects, meaning that we have no justification for absolutising bad habits into karmic laws.

Perhaps recognising some of these problems, another tack that advocates of karma sometimes take is to weaken it. “Karma isn’t an iron law” they say, “Karma just means actions having consequences.” By this, I presume they mean that it is useful for people to recognise and face up to the consequences of their actions, and indeed that those consequences may well be more far reaching and profound than they recognise. If that’s what they mean, then I thoroughly agree. But why call it karma, and thus in the process associate it with what has traditionally been seen very clearly as an ‘iron law’?

OK, they can define the term ‘karma’ in any way that they wish, and the arguments for doing so, in the end, are pragmatic ones. But I’ve yet to hear a good pragmatic argument for calling the ordinary, observable effects of our actions ‘karma’, and I can offer some strong pragmatic arguments for not doing so. The main one of these is that belief in karma is overwhelmingly understood, in both Buddhist and Hindu traditions, as a purely conceptual metaphysical belief about perfect payback, and that recognising the effects of our actions needs to be raw and experiential, not purely conceptual. I learn about the effects of alcohol through raw, embodied experience, not through deduction from some absolute belief about the effects of all actions. Indeed, associating it with an absolute belief is just likely to be a distraction at best, and more likely an exercise in ad hoc defense of tradition. The consequences of our actions are overwhelmingly particular, not general. The uncertainties of that realm of particular experience are basic to it. So the belief in karma tackles the matter from the wrong end of the spectrum: encouraging us, not to reflect on our experience and generalise about it in ways that can be applied to other situations, but to impose absolute top-down assumptions on it.

Another new talk edited from the 2014 retreat. This time it’s about how we can make better value judgements. There are lots of possible approaches (e.g. God, utilitarianism), but it’s argued that we need to avoid using any one of them absolutely or exclusively.

A new talk edited from the 2014 Summer Retreat, (and on a theme very relevant to this year’s retreat, on ethics). How can we find a Middle Way between assuming ourselves (and others) are totally responsible for what they do, or on the other hand assuming no responsibility?