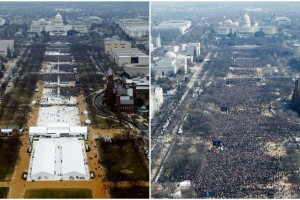

After the recent inauguration of Donald Trump, a row broke out about the number of people who actually attended the inauguration, in which Trump’s spokesperson was derided for using the phrase ‘alternative facts’. The evidence, as illustrated by the photos, seems pretty clearly not in support of the ‘alternative facts’ offered by the Trump administration, but I’m not interested in discussing the details of that (which have been much debated) here – rather I’m interested in the outrage attached to the idea of ‘alternative facts’. After all, the thinking seems to go, we have the facts here, so how can there possibly be alternative facts? A similar line of thinking seems to be behind the burgeoning phrase ‘post -truth’ – as if we used to know the truth, but now people aren’t accepting that truth any more. My view is that people who pay attention to evidence and try to develop personal objectivity are not doing their cause any favours by talking in terms of ‘post-truth’, but rather reinforcing the kind of confused thinking out of which the Trump phenomenon has been born.

Let’s first reflect on some basic features of the human condition, that we can all probably find in our own experience. We all have beliefs about the world, but those beliefs have also often turned out to be wrong, even if we held them along with lots of other people. This applies not just to ‘values’ such s the past belief that slavery is OK, but also to past ‘facts’ such as that the world is flat. As an individual, I can confess that I used to believe a number of ‘facts’ that I now no longer accept, such as that sisters are always older than you, that I would never be able to find a girlfriend, or that it’s safe to drive at 60mph over a moor with loose livestock on it. There are also the limitations of our senses, perspective, and most of all our language, which depends for its meaning on our bodies and metaphorical constructions, not some kind of correspondence with potential truth (for more on these sceptical themes, see this article). On the whole then, we must admit that we have no access to facts. It’s not just Trump who is deluded if he claims to know ‘the facts’ or ‘the truth’, but you and me too. Post-truth politics, along with post-truth philosophy and post-truth everything else, thus seems to have begun with homo sapiens as a whole, and our emergence of a capacity to hold and express any kind of belief that we might assume to be true. The first post-truth politician was the Serpent tempting Eve.

If we finger populist politicians for a fault that it can easily be seen that we all share, then, it is hardly surprising if we’re seen as hypocritical. Though I don’t see a lot of the often unpleasant social media output by Trump supporters, one thing that has struck me about a lot of what I have seen is the predominance of accusations of ‘liberal hypocrisy’. If liberals claim to have ‘the facts’ and respond to Trump’s excesses with blustering counter-assertions in a similar style, that accusation doesn’t seem to me wholly unjust. I think there are far more effective ways of responding that identify much more clearly what Trump and his henchmen are doing wrong and which avoid this ‘post-truth’ shortcut. It’s not whther they have or don’t have the facts, or don’t share your view of them, that matters here: but that they don’t offer those facts with provisionality, are not open to correction, are not interested in examining evidence or justification, are not even concerned about gross inconsistencies in their beliefs, and are not at all interested in improving on their beliefs or making them more adequate. In terms of values, they do not respect the truth or the facts. In relation to all these points, I agree very much with Trump’s critics that the new administration’s attitudes are extremely alarming.

If you genuinely respect the truth, you don’t claim to have it, just as if you respect the power of electricity, you don’t stick your finger in a live socket. Truth is a meaningful concept to us, because we use it in all sorts of ways in all sorts of practical contexts – for example, in science, in law, and in everyday conversation. We have set up an abstract model in which ‘truth’ stands for an idealisation – a fabled position in which we could really know what is going on, not just more than we did before, but totally, as in a God’s eye view. But nevertheless that abstract idealisation is just an extrapolation of our much more limited experience: the experience of recognising things we didn’t ‘know’ before, and of confidently interacting with the world around us in a consistent way. Most of the time, our confidence about how the world works turns out to be justified, so we apply this idealised concept of ‘truth’ to that experience, in the process completely failing to take into account the limitations of our view. So it’s very important that ‘truth’ is recognised as meaningful, and not relativised in its meaning, but at the same time recognised as beyond our reach.

Let’s take an example. A child brought up in a household with a friendly dog, confidently playing with it and interacting with it, thinks it’s ‘true’ that dogs are friendly. When he encounters the first unfriendly dog, though, his whole model of the world is briefly shaken, the ‘truth’ is shattered. There may be denial – the unfriendly dog doesn’t really count as a dog. There will certainly be initial stress, followed by suspicion and unease in a new uncertain relationship with dogs. But we don’t all have to be as fragile as that child, if we stop thinking in terms of ‘truth’ but rather cultivate the awareness that our beliefs are only justified for the moment on the basis of the evidence so far. If we can be aware of other possibilities to begin with, we will be less overwhelmed by the nasty surprise when it happens.

In the realm of politics, that means concentrating on the qualities that actually matter in making our judgements adequate, the ones that involve a larger respect for truth, rather than railing about others offering ‘alternative facts’: namely the personal qualities of provisionality, awareness, imagination and observation. It means setting the example to those who don’t understand this, and teaching children not to ‘tell the truth’, but rather to reflect upon and justify what they say. It means holding Trump to account, not for ‘lying’, but for being grossly inconsistent and failing to offer evidence or respond to criticism.

It may well be that most of those who complain about lack of truth, when pressed, would actually agree that what they value in practice are these ways of justifying and adjusting our beliefs. But while they continue to use ‘truth’ and ‘post-truth’ as a lazy shortcut, I think they will play straight into the hands of people like Trump. All that such populists have to then do when challenged is to turn back to their unsophisticated supporters, deny the criticism, and offer their own ‘alternative facts’. The discussion will then stay at the completely unfruitful level of mere claim and counter-claim. As our beliefs about the world are wrapped up with our goals, our ontological obsession with what is or is not ‘really’ the case is our biggest weakness, the absolutizing vulnerable spot in our cognitive abilities. It’s only by putting ourselves in the messy middle zone of neither accepting nor denying these ‘realities’ that we can make progress, whether in politics or any other area of human dispute.

Picture: Comparison between inauguration crowd sizes for Donald Trump in 2017 (left) and Barack Obama in 2009 (right). Images copyright to 58th Presidential Inaugural Committee (left) and ewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images (right), and are used at low resolution under fair use criteria.