Our guest today is Rupert Read, an Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, former spokesperson for Extinction Rebellion and co-director of the new Climate Majority Project. He’s authored several books, including This Civilisation is Finished, Parents for a Future and Why Climate Breakdown Matters and has been many times on the Today programme, Question Time, Newsnight, Politics Live, Al Jazeera, and more and he’s here to talk to us today about the Climate Majority Project.

Category Archives: Activism

Network Stimulus Politics 2: Political Action

The next main meeting of the Middle Way Network will be on Zoom at 7pm UK time on Sun 31st Jan 2021. This will be the second of two sessions on a Middle Way approach to politics. The first session focused on our political values and ideologies, whilst the second one will focus more on the practical dilemmas of political involvement of any kind.

Politics is often seen as an unavoidably polarised, and even corrupting, activity, so how can we manage to continue apply the Middle Way whilst being involved in it? However, at the same time many very important conditions and issues impacting our lives seem to demand political involvement. Much depends on where we start as individuals, and whether we can manage to maintain a sense of balanced perspective when we become politically involved. There is also a spectrum of political activity we can engage in, from merely voting, via online discussion and ‘clicktivism’, to active campaigning, party membership, and even standing for office.

In this session, we’ll be talking about the overall framing issues of finding the Middle Way in political action in the talk and initial Q&A, and the breakout groups should then provide the opportunity to apply this more to your personal situation and share your experience.

There’ll be a short talk on this topic, followed by questions, then discussion in breakout groups, and a plenary session at the end. At the main meeting, for this session only, we will be mixing up the normal regionalised breakout groups to help people get to know each other across the Network. If you’re interested in joining us but are not already part of the Network, please see the general Network page to sign up. If you would like catch up more with basic aspects of the Middle Way approach, we are also holding a reading group (next on 7th Feb) which will do this – please contact Jim (at) middlewaysociety.org if you want to join this.

Here is the video from this session:

Suggested reflection questions

- In what ways have you been politically involved? How easy have you found it to maintain a sense of Middle Way perspective in these political activities?

- How do you think you could help set up the conditions for a more Middle Way approach to political activities?

Suggested further reading/ listening

Depolarising politics talk 2: Activists or Quietists?

Migglism, Part 4: ‘Politics’

Truth on the Edge, ch.9

The ‘3.5% rule’, stubborn minorities and tipping points

The recent protests in the UK by Extinction Rebellion have stimulated discussion of the so called ‘3.5% rule’, that 3.5% of population need to join a protest movement for it to succeed. This is based on research by Erica Chernoweth, which is discussed in this BBC article. Chernoweth looked at a variety of protest movements, and found they tended to succeed if they reached that threshold, as we see for instance in the civil rights movement in the US in the 1960’s and quite recently in the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan.

How can a whole society be changed by such a relatively small proportion of people? It all depends how determined they are – but if they have taken to the streets, even willing to face arrest or potential violence, they are obviously resolved. This research seems to offer an example of a much wider property of systems, whereby it only takes a relatively small but unyielding element of a system to force a modification in the way the whole system operates. I have come across this same point discussed from different standpoints in two other places: Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s book Skin in the Game (2018) and Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point (2000).

Taleb talks about the power of stubborn minorities, giving the example of orthodox Jews who want food labelled kosher obliging US food manufacturers to include it on their label. The proportion of orthodox Jews in the US is, according to Taleb, only 0.3%, but nevertheless, because this 0.3% were very definite and uncompromising about what they wanted, and because it did not require any great sacrifice on a food manufacturer’s part to label kosher food as such, they did so. So you may not need anything like as much as 3.5% if not too much is demanded of everyone else.

Taleb’s other example is the gradual replacement of Muslims for Coptic Christians in the population of Egypt. The Copts are now a minority of about 10% of the Egyptian population, but after the Muslim takeover in the eighth century they were the great majority. The Muslims were tolerant and did not force anyone to convert. What made the difference, however, is that Muslims refused to contract marriage with anyone who did not convert to Islam. All it took was that degree of unyieldingness, over many centuries of just a trickle of mixed marriages, for the Coptic majority to become a minority.

Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point approaches the same phenomenon from the standpoint, not of minority resistance, but of minority enthusiasm. He offers story after story of new products or ideas that suddenly ‘took off’: hush puppies, Blue’s Clues, The Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood. The apparent causes of them doing so are not consistent, but in every case a kind of group epidemic occurred: the product suddenly ‘went viral’ after passing a ‘tipping point’. The sales chart started rising, not arithmetically, but exponentially. It’s clear that there are lots of reinforcing (or closed) feedback loops going on that are leading more and more people to adopt the product, because it has become a mark of acceptance by the group to do so.

What does all this have to do with the Middle Way? Well, it seems likely to me that what is often, though not always, going on, when people reach a tipping point of this kind, is absolutisation. People get into feedback loops in which the desire for the new thing (or rejection of the old thing) is driven by obsessive desire for social acceptance (or fear of losing it), and such feedback loops have the effect of producing sudden exponential change. That change is easy for even a very small group to achieve when the sacrifices demanded are small and the resistance is low (as in labelling kosher food), and require the magic 3.5% when there is some resistance, but the majority resistors are still much less strongly motivated than the minority.

But do minorities always only get what they want through absolutisation? I suggested that absolutisation may often be the source of the unyieldingness, but not always. Instead, it must be possible to be unyielding for far more justifiable and considered reasons – that one is confident of one’s cause, that it is supported by good evidence, and that it is far better justified than any alternative view. This, I hope, is what we are seeing with the campaigns of Extinction Rebellion. All the evidence I have seen so far suggests that they are very careful to try to combine a sense of urgency with calm. We need to ‘panic’ in the sense of acting urgently in response to the climate emergency, but not to ‘panic’ in the sense of locking ourselves into closed feedback loops of obsession or anxiety. This suggests that a tipping point can be reached, on a genuinely important issue, by following the Middle Way rather than any absolutized belief.

However, we also need to beware of the same phenomenon being utilised by absolutists, whether it is to advertise a product, spread a conspiracy theory through social media, or get people to accept a simple idea (like Brexit) that is grasped at as a false solution to complex problems. It takes a lot of effort and difficulty to reach a tipping point without absolutisation – but to do it with absolutisation seems so much easier! Fast thinking and easy solutions are always appealing, but there is no alternative to the harder road to the tipping point if you want to make the world a better place.

Picture by Michal Parzuchowski (Unsplash)

The MWS Podcast 145: George Monbiot on Rewilding

Today’s guest is the British environmental writer and political activist George Monbiot. George writes a weekly column for The Guardian, and is the author of a number of books, including Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain (2000) and Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding (2013). He will be discussing the topic of rewilding with the chair of the Middle Way Society, the philosopher Robert M Ellis.

MWS Podcast 145: George Monbiot as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_145_George_Monbiot

Stream podcast from Itunes Library

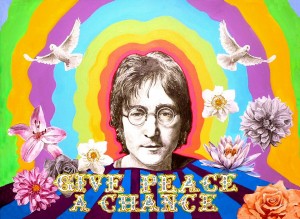

How to Solve a Problem Like John Lennon

‘Part of me suspects that I’m a loser, and the other part of me thinks I’m God Almighty’.

John Lennon was, with Paul McCartney, one half of the greatest song writing duo in history, and one quarter of the greatest bands in history: the Beatles (as very rare examples of absolute facts these, perhaps, represent the only time when Middle Way notions of provisionality, incrementality and agnosticism do not apply). Nevertheless, some would also have you believe that Lennon was a peace-loving, feminist icon who fought for the rights of the disenfranchised and the oppressed. A man who declared that ‘all you need is love’ and dared to Imagine a world without war, nationalism or religion. Others present him in an altogether different hue: as a violent, jealous and chauvinistic bully who abused his first wife, Cynthia and emotionally neglected his first son, Julian. On one hand we have Lennon the hero and on the other we have Lennon the villain and in many cases he is presented as either/or, with commentators unable, or unwilling to negotiate this juxtaposition. Sometimes, biographical accounts will even skim over, or ignore these conflicting characteristics entirely and instead focus solely on his musical career. I remember watching a biographical documentary which, apart from briefly referencing his peace activism (and judging it to be an immature and naive embarrassment) did exactly that.

‘When you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out… in’.

There’s a tendency to dehumanise those whom we cast as heroes or villains, creating one dimensional figures to be loved or reviled. This tendency is apparent with the treatment of exceptional individuals throughout history, such as Saints, military heroes and political activists. The recent rise of the celebrity (a term which often invites scorn, but is actually an umbrella term covering people with a wide range of skills and achievements, like Elvis Presley, Princess Diana or anyone who appears in any reality TV program) has provided  another category. There clearly seems to be a need for us to create simplified archetypes and doing so does appear to be useful, but to do this with historical people that have lived (or are still alive) can deny us a richer understanding of their, and consequently our own, humanity (and can also create real dangers, as chillingly demonstrated by the recent case of Jimmy Savile).

another category. There clearly seems to be a need for us to create simplified archetypes and doing so does appear to be useful, but to do this with historical people that have lived (or are still alive) can deny us a richer understanding of their, and consequently our own, humanity (and can also create real dangers, as chillingly demonstrated by the recent case of Jimmy Savile).

‘Well, you know that I’m a wicked guy

And I was born with a jealous mind’.

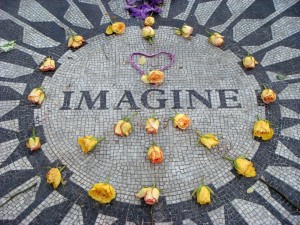

Lennon’s lyrics often seem like raw, unguarded confessions that reek of insecurity and contradiction. He seemed to be keenly aware of the conflicting aspects of his personality and didn’t shy away from exploring them in the material he released. He acknowledged both the good and the bad; the hero and the villain. While he declared that ‘all you need is love’, he also put to song the disturbing words ‘baby I’m determined and I’d rather see you dead’. Filling the space between these two extremes was a Scared, Jealous Guy who felt in serious need of Help! A perfect example of this uneasy juxtaposition can be found on the Imagine album. As well as featuring the well-known title track, which has become something of a secular hymn, it also contains the track How Do You Sleep?, a venomous attack on his former writing partner and friend, Paul McCartney, which couldn’t be any further from the sentiments expressed in Imagine.

‘Hatred and jealousy, gonna be the death of me

I guess I knew it right from the start

Sing out about love and peace

Don’t want to see the red raw meat

The green eyed goddamn straight from your heart’.

He admitted that he had been physically abusive to women – not just Cynthia – and that he had not been a very good father to Julian. He admitted that he was a bully. He also described his own experiences of childhood abandonment and later feelings of fear and insecurity, which he concealed behind a mask of buffoonery and violence. Not that this excuses the behaviour of a grown man, but it does provide us with some sense of a complex human being. Add to that his later promotion of pacifism, feminism and social justice and the asymmetrical mosaic grows greater still. In the later years of his life he became a devoted parent to his second son, Sean – with whom he seemed able to attain some sense of atonement. Unfortunately, his relationship with Julian remained strained and distant. Maybe the old wounds would have healed, had he not been shot and killed at the age of 40, but perhaps his earlier behaviour had been too damaging.

‘I really had a chip on my shoulder … and it still comes out every now and then’.

There are those that might cry ‘hypocrite’ at such apparent contradictions, but that would be over-simplistic and unfair. It’s quite possible for Lennon to have been all of these things over time (or even simultaneously), with some characteristics perhaps being the consequence of another. For instance, it’s likely that his feminism grew, in part, out of a need for redemption. That’s not to say, then, that the villain of the piece was defeated; forever to be vanquished by the upstart hero and his eye shatteringly shiny armour. No, far more likely was that the two existed side by side in an on-going (and probably uncomfortable) process of conflict and negotiation. Acknowledging someone’s flaws does not necessitate that one question the sincerity of their strengths.

‘Although I laugh and I act like a clown

Beneath this mask I am wearing a frown

My tears are falling like rain from the sky

Is it for her or myself that I cry’?

A minor deviation here, but I would like to comment on the supposed naivety and immaturity of Lennon’s political views. First of all, I feel that this is a misrepresentation of what he actually said. If we look at the two main points that critics tend to pick up on: the invitation to imagine everybody living in peace and the request to give peace a chance. Both of these notions seem far from naïve to me, in fact they seem like reasonable suggestions for incremental change. There is clearly no unrealistic demand for overnight change; just a suggestion that we consider an alternative way of conducting ourselves, with the hope that things might start to get better. In the UK similar accusations are levelled at Jeremy Corbyn, and they grate with me for the same reasons. I’m not suggesting that anyone has to agree with either Lennon or Corbyn, but the condescending disregard of their, perfectly valid, views strikes me as being unnecessary and spiteful. Secondly, the generalised criticisms of Lennon’s political views assume a fixed ideology that just doesn’t seem to have been present. He changed, altered and evolved his ideas all through his life, and was often critical of things that he had previously said or done.

A minor deviation here, but I would like to comment on the supposed naivety and immaturity of Lennon’s political views. First of all, I feel that this is a misrepresentation of what he actually said. If we look at the two main points that critics tend to pick up on: the invitation to imagine everybody living in peace and the request to give peace a chance. Both of these notions seem far from naïve to me, in fact they seem like reasonable suggestions for incremental change. There is clearly no unrealistic demand for overnight change; just a suggestion that we consider an alternative way of conducting ourselves, with the hope that things might start to get better. In the UK similar accusations are levelled at Jeremy Corbyn, and they grate with me for the same reasons. I’m not suggesting that anyone has to agree with either Lennon or Corbyn, but the condescending disregard of their, perfectly valid, views strikes me as being unnecessary and spiteful. Secondly, the generalised criticisms of Lennon’s political views assume a fixed ideology that just doesn’t seem to have been present. He changed, altered and evolved his ideas all through his life, and was often critical of things that he had previously said or done.

‘My role in society, or any artist’s or poet’s role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all’.

While I probably wouldn’t go so far as to put Lennon forward as a Middle Way Thinker, I do think he provides a good example of how a Middle Way approach can be useful in the consideration of those whom we admire… and those we do not. Gandhi (who has featured in Robert M Eillis’ Middle Way Thinker series) could, with some justification, be accused of misogyny and racism, but that doesn’t take away from his achievements or the legacy he left behind. The medieval Saints of Europe become figures of greater interest and inspiration when their multi-dimensional and flawed humanity can be glimpsed beneath their holy veneers (a principle that, I have recently discovered, can be applied to Jesus too). Of course, such figures need not be well known. We also create heroes and villains in our day to day lives too; looking up to, or down upon family members or colleagues, for instance. If we can recognise the messy middle from which others are composed and accept that people can be both good and bad, in different measures, at different times, then this might just enable us to become more open to those around us and more accepting of ourselves. This sounds easy on paper, but can be difficult to achieve in practice. I, for one, have a long way to go but the closer I look, the more complicated the picture becomes and the easier it gets.

While I probably wouldn’t go so far as to put Lennon forward as a Middle Way Thinker, I do think he provides a good example of how a Middle Way approach can be useful in the consideration of those whom we admire… and those we do not. Gandhi (who has featured in Robert M Eillis’ Middle Way Thinker series) could, with some justification, be accused of misogyny and racism, but that doesn’t take away from his achievements or the legacy he left behind. The medieval Saints of Europe become figures of greater interest and inspiration when their multi-dimensional and flawed humanity can be glimpsed beneath their holy veneers (a principle that, I have recently discovered, can be applied to Jesus too). Of course, such figures need not be well known. We also create heroes and villains in our day to day lives too; looking up to, or down upon family members or colleagues, for instance. If we can recognise the messy middle from which others are composed and accept that people can be both good and bad, in different measures, at different times, then this might just enable us to become more open to those around us and more accepting of ourselves. This sounds easy on paper, but can be difficult to achieve in practice. I, for one, have a long way to go but the closer I look, the more complicated the picture becomes and the easier it gets.

‘We all have Hitler in us, but we also have love and peace. So why not give peace a chance for once’?

Songs Quoted (In Order of Appearance)

All You Need Is Love (Lennon-McCartney, 1967)

Revolution (Lennon-McCartney, 1968).

Run For Your Life (Lennon-McCartney, 1965).

Scared (Lennon, 1974).

Loser (Lennon-McCartney, 1964).

Pictures (In Order of Appearance)

Lennon Memorial Plaque, courtesy of Pixabay.com.

John Lennon Beatles Peace Imagine, courtesy of Pixabay.com.

The Beatles & Lill-Babs 1963, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine John Lennon New York City, courtesy of Pixabay.com.