For a new review by Robert M Ellis of ‘The Middle Way’ by Lou Marinoff see this link

Category Archives: Philosophy

Middle Way Thinkers 3: Aristotle

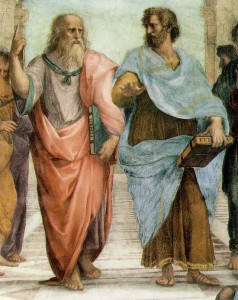

In Raphael’s famous picture ‘The School of Athens’, the highlighted two standing philosophers in the middle are obviously intended to be the most important. They are Plato and Aristotle. Plato is pointing upwards, symbolising rationalism and its appeal to transcendent reason, but Aristotle is pointing downwards towards the Earth, to symbolise the empirical appeal to experience and the earth. The Buddha is also sometimes depicted touching the ground, in a way that could be taken to symbolise the ‘groundedness’ of his view of things.

In Raphael’s famous picture ‘The School of Athens’, the highlighted two standing philosophers in the middle are obviously intended to be the most important. They are Plato and Aristotle. Plato is pointing upwards, symbolising rationalism and its appeal to transcendent reason, but Aristotle is pointing downwards towards the Earth, to symbolise the empirical appeal to experience and the earth. The Buddha is also sometimes depicted touching the ground, in a way that could be taken to symbolise the ‘groundedness’ of his view of things.

The Buddha’s relationship to experience can be seen as the basis of his Middle Way, avoiding either positive or negative metaphysical claims. But can we say the same for Aristotle? The resemblances, at first sight, are striking. Not only is Aristotle often regarded as the first empiricist in the Western tradition (and also the founder of Western science, the first to seriously use observation to support his claims), but he also taught a virtue ethics, with the famous Golden Mean as a guide to how we could identify a virtuous quality. A practical virtue, he said, is found mid-way between the excess and the deficiency of a quality. For example, courage (a true virtue in his view) is found mid-way between cowardice (the deficiency of courageous quality) and foolhardiness (its excess). Is this an ancient Greek version of the Middle Way?

Sadly, not quite. There is much to admire in Aristotle. He was a multi-talented figure who took an interest in everything from biology to poetry. He learnt from his master Plato and went beyond him. His Ethics, and particularly the chapter on friendship, are of particular interest today. Aristotle can be a great source of inspiration, but he should certainly not be assumed wholesale to have hit the Middle Way. Nor should the Middle Way be described as ‘Aristotelian’. For there are still some basic ways in which Aristotle remains in a set of metaphysical assumptions that might take us off in a different direction.

Aristotle did challenge the metaphysics of Plato, but he also developed his own metaphysics. Rather than basing this on absolute reason like Plato, he made the assumption that we could observe the truth about the world through the senses. Where Plato evidently believed that the Forms (ultimate essences) lay in reason alone beyond the world, Aristotle believed that they lay in each individual thing in the world. Through observation we could work out the essence of a thing, and thus its true purpose. He thus assumed that the world was formatted in a way that would allow scientists to understand it correctly, and that observation of human beings could also show us their true nature and purpose. ‘Man’ he famously wrote, ‘is a rational animal’: meaning that what is essential and distinctive about humans is their rationality. Our true purpose, he believed, can thus be fulfilled by developing that rationality.

The Golden Mean, then, needs to be understood in its context. It’s not a method for taking into account the limitations of our understanding in the whole of experience, as I take the Middle Way to be. Rather it is Aristotle’s account of how he thinks humans can be good and fulfil their true purpose. He believes that we should develop our rational virtues, which help us judge whatever we meet, but we should also develop our practical virtues , which are gained through practice and involve a balance between excess and deficiency. Instead of using the Middle Way to judge both facts and values, Aristotle treats each differently. The facts, he thinks, are known by examining the world and understanding the essential truths about each thing and its purpose. Right values, however, are developed by applying what we have learnt, even though doing that requires practice as well as theory. Even though he has an attractive ethics that emphasises balance and has a strong practical aspect, Aristotle was a naturalist.

Aristotle’s general approach can thus easily be used to justify practices that are believed to have been observed in the world, even though they’re obviously the product of the assumptions made by the observers. That’s why his ideas are still invoked by the Catholic Church today (via their interpretation by St Thomas Aquinas) to support the belief that sex is ‘naturally’ for procreation, and that to use it merely for pleasure is a sin. One can, of course, observe the link between sex and procreation, but the belief that procreation thereby becomes the essential purpose of sex, and then that to do otherwise is wrong, involves a whole pile of dogmatic assumptions.

To get closer to the heart of the Middle Way in ancient Greek philosophy, I think, we must look instead to Aristotle’s near-contemporary Pyrrho. I will discuss Pyrrho in more detail some other time, but the key point here is that Pyrrho was able to pursue sceptical arguments against the supposed ‘truths’ that Aristotelians thought they were able to observe. Sceptical arguments show that there can be no such known ‘truths’, only provisional beliefs. Pointing us downwards towards our experience is a step in the right direction, but empiricism, too, can be dogmatic. It’s only if we can hold our empirical beliefs with genuine provisionality that we start to get closer to the Middle Way.

Middle Way Thinkers 1: David Hume

This is the start of a new blog series on Middle Way Thinkers (the meditation series will continue, but with more varied contributors and less frequently). What I mean by a ‘Middle Way Thinker’ is a well known person of the past or present who has made a major contribution to our thinking about the Middle Way. There is already a page on the Buddha on this site but not much on anyone else. I’m going to offer a bit of background and a summary of some key ideas of each figure, and try to distinguish their ideas that support the Middle Way from those I think less helpful. It’s not going to be restricted to philosophers, but may include all kinds of thinkers from different cultures and times.

I’m going to start with David Hume (1711-1776) because I have such a soft spot for him, and he made such a creative contribution to philosophy, despite his mistakes and imperfections. Hume was born to a family of minor gentry in the borders of Scotland and attended university in Edinburgh at the age of 12 (normal in the eighteenth century!). He was given to philosophical reflection from an early age, but also inspired by the ‘Scottish Enlightenment’ that was taking off during his life. He lived at various times in London, France and Edinburgh, but his major work A Treatise on Human Nature, was composed while he was on a kind of study retreat at a rural French college called La Fleche. He poured his amazingly new ideas into the Treatise, but it fell ‘still-born from the press’, as Hume put it, gaining few readers. Although he then tried to present his ideas in new forms (his two Enquiries), he eventually got so disillusioned with the lack of public response to his philosophy that he turned to writing history instead.

What’s so thoroughly important to the Middle Way in Hume is his emphasis on experience as the basis of our judgements. Although there were empiricists (such as Aristotle and Locke) before Hume, they were not nearly as thorough and rigorous in their allegiance to experience as Hume was. Unlike his predecessors, Hume applied the criterion of experience to areas like the self, causality, ethics and religious belief. Where his predecessors had been patchy in their allegiance to experience, sometimes falling back on dogma when the going got tough, Hume followed it through all the way.

For example, Hume recognised that you cannot actually experience a cause – all you experience are two events that you generally assume are linked because they occur so frequently in succession. One billiard ball hits another and apparently causes it to move, but we only have the frequency of their interaction as the basis to call this a ’cause’. Similarly, Hume recognised that when we look inside our experience we don’t actually find a self, just a lot of experiences of thoughts, feelings etc. that we tend to assume are ‘ours’. The ‘me’ label that we apply to these is just a label, as we don’t find a separate ‘me’ amongst the thoughts and feelings.

But perhaps Hume’s biggest achievement, in my view, is what is often known as ‘Hume’s Fork’. You can imagine Hume’s fork as a binary choice, like a fork in the road, and it applies to claims. Either, he said, a claim tells us something relevant to experience, or it tells us something about the relationships between ideas. We can’t accept that claims about relationships between ideas tell us anything relevant to experience. Here is the blistering way he puts this in the rousing finale of his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding:

When we run over libraries, persuaded of these principles, what havoc must we make? If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning of quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matters of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.

I think this is the first attack on metaphysics in Western philosophy. He was basically pointing out that a claim that is only concerned with the ultimate and abstract zone beyond experience (what philosophers call the a priori) can do not more than tell us about the conventions that we apply when trying to understand the universe. It tells us nothing about the universe itself, or for that matter about ourselves or our values. To assert that it does is deluded in a very basic way that confuses the sign with the reality. In this sense he was independently revisiting some of the insights of the Buddha.

However, as with every other philosopher, there are also ways that I think Hume veered significantly from the Middle Way. I think his biggest mistake was the fact-value distinction, which he virtually invented. Hume assumed that because we need to justify our beliefs in terms of experience, we have to confine our beliefs to factual ones that can be justified through scientific observation. A justifiable ethics for him would also have to be based on factual observation about acceptable moral attitudes in society. This popularised the regrettable assumption, that haunts a lot of Western thinking to this day, that ethics is inherently subjective – in contrast to ‘facts’ which can be absolutely objective. This is a false dichotomy for which we have paid with much confusion.

Nevertheless, on the whole I tend to find Hume an inspiring figure. He was a courageous figure prepared to think things through, defy the establishment, and trenchantly reject dogma wherever he found it. But despite his free-thinking, he was no dour Scottish puritan – rather an imperfect human figure who liked a good dinner and enjoyed the pleasures of friendship.

Some web links on Hume:

- http://www.davidhume.org gives free access to all Hume’s published works

- http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/authors/hume.html offers modernised texts to make Hume easier for modern readers

- http://www.humesociety.org . Scholarly society devoted to Hume

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hume : a good place to start for an overview

- http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hume : Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- http://www.iep.utm.edu/hume : Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The MWS Podcast: Episode 20, Don Cupitt

In this episode we are joined by the Christian theologian and philosopher Don Cupitt. He talks to us about how he understands religion and his non-realist position about God. He also touches on Jungian archetypes, agnosticism, Stephen Batchelor and how he views the Middle Way.

MWS Podcast 20: Don Cupitt as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_20_Don_Cupitt

The MWS Podcast: Episode 19, Peter Worley on teaching philosophy to young children

In this episode, we are joined by Peter Worley, the co- founder of the Philosophy Foundation and author of the ‘If Machine’ and the award winning ‘Philosophy Shop’. The main topic is teaching philosophy to children and philosophy’s wider role in education.

MWS Podcast 19: Peter Worley as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_19_Peter_Worley