To say that the last couple of days have been eventful in British political life would be an understatement. A narrow vote to leave the EU in the referendum on 23rd June confounded widespread assumptions of the permanence of the status quo. As had been widely predicted, an economic storm blew up immediately. But what is even more notable is what has happened since: not only Cameron’s resignation, but widespread reports of ‘Bregret’ – those who voted leave saying they would change their minds next time, because they hadn’t realised it would actually make a difference. At the time of writing, a petition on the government petition site has gathered over 2 million signatures calling for a second referendum.

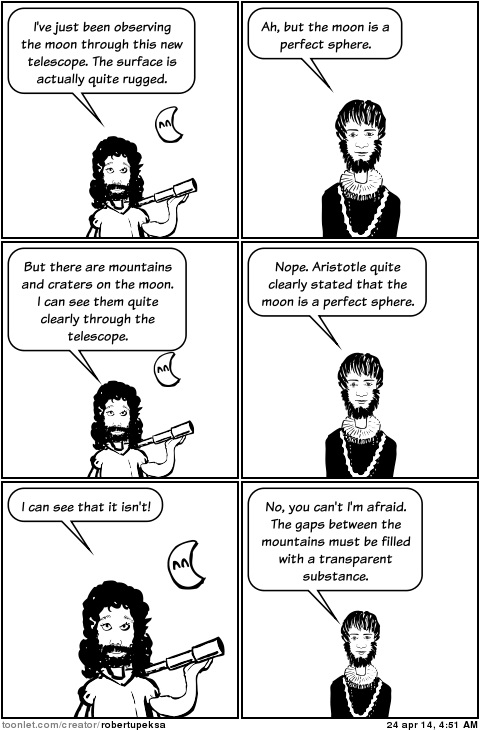

What does all this have to do with the Middle Way? Pretty much everything. Remember, the practice of the Middle Way starts right now in whatever situation we are in, finding a point of balance and avoiding either sort of absolutisation, positive or negative. I suspect that most readers of this blog will greatly regret the current situation, and may feel that it’s really unjust, or perhaps a few will feel that it is just: but either of these responses are idealisations of a complex situation. The degree of justice or injustice lies in people, not in the whole situation, so probably the first move in finding a point of balance is to recognise and avoid implicit cosmic justice assumptions or their denial. Related to these may be other absolutisations: absolute blame heaped on one person or group or another, or absolute value applied to the consequence of either leaving or remaining in the EU. Such abolutisations obscure our understanding of the conditions involved.

It is avoiding these absolutisations that can enable us to judge the situation in a more balanced way, but it does not free us from political concerns. Nor does it release us from recognising the degree of justice and injustice, appropriate praise and blame, or right and wrong that need to be applied in understanding the situation. Examination of the process of events can reveal a whole set of biases and fallacies that have both created receptivity for the misleading narrative for ‘Leave’ and also made the ‘Remain’ campaign ineffective.

Personally I think fairly strong moral conclusions can still be reasonably drawn whilst avoiding absolutisation. I think that the leaders of the ‘Leave’ campaign have behaved in a disgracefully dishonest fashion, and that the English and Welsh working classes have been duped. These are generalisations, which will of course have exceptions, and we can also recognise an interdependency between the naivete of the voters and the lack of integrity of the politicians and of the tabloid media. Neither is wholly to blame, but at the same time considerable blame can be fairly apportioned. The evidence is clear if, for example, we look at the simplistic figure of £350 million pounds a week allegedly given to the EU, the treatment of the issue of possible Turkish accession to the EU, or the treatment of the issue of the economic and social impact of EU migrants in the UK. On the whole, the politicians offered simplistic slogans that obscured the issues, these slogans were passed on without any critical context by the tabloids, and when questioned about them the politicians concerned resorted to diversionary tactics such as ad hominem attacks. The falsely neutral BBC rarely got any further than ‘balancing’ one ad hominem attack against another, letting through unscrutinised no end of misleading mono-causal explanations for complex phenomena or statistics taken out of context. Only a few more specialised and less popular programmes examined the issues more deeply.

Conclusions like these can be drawn, but we also need to start by coming to terms with the new conditions. Yes, it seems that we have a bitterly divided UK with an alienated, ignorant and even blindly furious working class largely at the mercy of whatever media and political interests are best able to manipulate them. Failing to understand the conditions, this group have collectively engaged in a massively self-destructive act. But we won’t be able to address these conditions if we think that somehow God has made a mistake and it really shouldn’t have been allowed, or that some other intrinsic justice has been betrayed. Nothing finally ‘wrong’ has happened: rather people have made mistakes, and these can be improved upon.

Trying to reach that position of balanced judgement, I still think we can find ways forward and find grounds for optimism. The underlying problem is that people have absolutised in their judgements, because they have not had the training in critical thinking to be aware when they were being fed a narrow account of conditions, nor the training in other integrative practices to move beyond one particular dominant idea (say that of ‘getting our country back’) that has dominated their judgement. This can be changed, but only in the long term. People can be trained in integrative practice and in critical thinking by more effective education, not just at school but throughout life. People can also be greatly encouraged to think more critically about political claims by a more effective and genuinely critical media. As individuals, we can also contribute to them spreading one-to-one even if we do not work in either education or the media.

I would like to contribute to campaigning in both those crucial areas – education and the media – but if forced to choose between them, I am most struck by the responsibility of the media for the situation. That responsibility emerges from a complex web of conditions: the operation of market forces on media organisations, the constant interplay between journalistic creativity and audience expectations, and so on. Yet my impression is that most journalists, even those working for the most reputable newspapers or broadcast organisations, do not see critical thinking as part of their brief, and are simply not trained in it. If journalists really want to give the public the tools to draw their own conclusions in an informed way, they need to become much more aware of the terminology and techniques of critical thinking and of practically applied cognitive psychology. At the moment, for the most part, they are simply not holding politicians to account, because the politicians remain effectively unchallenged in the ways that matter most. Being rude, interrupting the politician and telling them they have not answered the question are simply not enough if endless ad hominems, straw men, false dilemmas, simplistic mono-causal explanations, raw statistical figures without contextual proportions, or dismissals without a practical alternative go straight past them. If the public are not interested enough or aware enough of these things, it is both the job and the talent of journalists to make them interesting, and in the process start to contribute to a more objective and more adequate politics in the future.