My relationship with Jesus of Nazareth has recently changed for the better. I’ve never felt particularity negatively towards him, as I have towards God (I just can’t respond well to a character who encourages filicide, slavery, bigotry and genocide, to satisfy their own jealous insecurities) and have always found his depiction to be strangely captivating. Yet I have not consciously regarded him as a figure of inspiration; I always felt that he was the property of practising Christians, and anyway, wasn’t he the Son and earthly manifestation of the God that I find so problematic? This, I am pleased to report, is no longer representative of how I feel (about Jesus, at least) and I’d like to spend some time explaining how this change of heart has come to pass.

As the assumed Son (and earthly manifestation) of a perfect God, it has always been posited to me that Jesus must also be perfect; this was either something you believed in or you didn’t, take this view of Jesus or don’t take him at all. I assumed that as there are compelling arguments to suggest that the Abrahamic God is far from perfect, then it must also follow that Jesus could not be perfect. Further confirming this view, a recent reading of the New Testament revealed a sometimes flawed and aggressive Christ rather than the serene, unshakably tolerant, haloed figure of Christian tradition. This Biblical character seemed leagues apart from the perfect Jesus that I’d been taught about, through art and carefully selected Bible readings. I also had the suspicion that even if I did find inspiration in Jesus, I could not do so openly and easily without belief in God – as an atheist (hard agnostic) I have often been asked (sometimes forcefully) why I celebrate Christmas, and the fact that my wife and I were married, as atheists, in our local parish Church has also caused confusion and even offence. When I considered all of this alongside the glaring inconsistencies in the New Testament my response was one of rejection.

In the past year or so I have read two books that have caused me to think again: Zealot by Reza Aslan and Jesus for the Non-Religious by John Shelby Spong. Although I discuss them here, this is by no means supposed to be a detailed analysis or synopsis. I would, however, recommend them both for reading. Aslan spends a lot of time exploring the historical context of Jesus’ life and of the subsequent writing of the books of the New Testament. I think he does this well and draws many interesting conclusions. The main one being that Jesus was a radical Jew who, as part of a wider movement, challenged the authority of Rome and perceived corruption of the priestly class, and despite being unsuccessful had a profound impact on those that followed him. In the decades after Jesus’s death and in the wake of the Roman’s retaliatory destruction of Jerusalem (following their successful expulsion), the foundations of the Christian church were laid – by some that knew him and by many that did not. Interesting as they are, such conclusions were not the most affecting aspect of my time with this book. Rather, by thinking about Jesus as a human being and the New Testament as a series of documents – both worthy of historical analysis and set within a surprisingly (for me at least) well understood historical context, I found that my entrenched rejection began to subside. The fact that Jesus might have existed (and I think it seems likely that he did, given the short time in which his cult developed following his death) and that I felt able to explore this possibility, without feeling that I should harbour some sort of Christian belief, has become fundamental to the way I am able to engage with him and the texts in which he appears.

One can argue, rather successfully as it happens, that to be inspired by Jesus’s life and message requires neither Christian belief nor interest in the historical figure. I agree, to an extent; why should one have to suspect that Jesus existed to respond positively to his message of forgiveness? One doesn’t. Nonetheless, by doing so I have been able to attain much more meaning from the Jesus story than I could before. Why then, should it matter if individuals or events can be argued to be historical in relation to the meaning they have for me?

Take the image of Father Christmas. I’ve long believed that the red and white colour scheme of his outfit was designed and introduced by Coca-Cola as part of a marketing campaign. Red and white are the identifying colours of the company and they do have an irritating habit of plastering Santa’s image over a massive articulated lorry that appears on their festive adverts and visits various towns and cities. It came to my town this year and people went wild, standing round it in large crowds staring excitedly – filming it on their mobile devices, no doubt. Anyway, this association with a) the advertising industry and b) a multi-national company, that has a rather chequered ethical reputation, tarnished the meaning of images of Father Christmas for me. I still had fond memories of childhood, of family getting together in merriment, of nativity plays, of Christmas smells (the list goes on) – but they were mixed up with notions of cynicism, commercialism and exploitation of communities in the developing world. Of course, the whole Christmas season involves these things, it is a time of excessive contradictions, but the idea of this treasured figure from my childhood being the cynical marketing construction of a company that I have had ethical concerns about distilled this somehow. Thus, I was quite delighted to find out that the story is probably not true. Yes, Santa’s image is widely used for cynical marketing purposes, but the fact that his traditional image is used, rather than having been created for, this purpose seems to matter to me. The story of Coca-Cola creating Father Christmas’s modern image still exists, but the knowledge that it is likely a misconception, rather than historical event changes, for me, the nature of its meaning, and the meaning of depictions of Santa.

Walter White and the series Breaking Bad provide another example of how confidence in the historicity of events can impact on the meaning they may have on an individual. I loved Breaking Bad; I didn’t want to, because of its popularity, but I did. The series is harrowing in places and the actions of White become increasingly extreme and difficult to justify. It skilfully explores a wide range of ethical issues, and I often found myself questioning not only the characters, but myself. However, if I’m honest, I was always on the side of White. No matter what he did, I was with him all the way. Now, if I ‘d gone into the series with the belief (or found out after) that it was either a biography based on actual events, or that it was a documentary, I would have had a very different response to White and his activities. The ethical questions would still be there, as would the wonderful grey morality in which the story revels, but my response, both intellectual and emotional would be very different; White and his story would have had different meanings for me.

By thinking about Jesus without personal associations of Christian dogma, I’ve been able to imagine, with varying degrees of confidence an individual of greater scope and depth. This does not require a separation of Jesus from either Jewish or Christian belief. Nobody seems to quarrel when historians study Alfred the Great or Joan of Arc. Both individuals were pious Christians, both have mythologies that blur the lines between history and fiction, and one does not have to share their beliefs to study or take inspiration from them. It seems acceptable, in a way that it often isn’t with Jesus, to examine the evidence and conclude with a degree of confidence that each of these figures existed and that some life events are more likely to have occurred than others. Joan of Arc (like most historical figures) is both a figure of mythology and of history, there is no conflict and the lines between the two need not be distinct. If I consider the possibility of Jesus as the radical reformative Jew described above and then take a hard-agnostic view on the possibility of him being the Son of God (whether he thought he was or not is often debated, but there is at least the possibility of finding historical evidence) then Jesus ceases to be perfect, and this is a good thing. Apart from being more interesting, his sometimes erratic and even intolerant behaviour becomes less problematic. As a human in a specific historical context, he can be excused for being imperfect, or even morally questionable in a way that God cannot. The New Testament can be similarly viewed. Even more than Jesus (who is not around today), the Bible has a history, its various books can be placed, with varying degrees of accuracy, within historical times and places. The authors need not be identified to understand the context in which they were written. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle is a vast document that details events over a long period. It’s often contradictory and seems to freely mix fiction with historical events and yet it’s place as an important historical document is rarely questioned. I don’t have to have the same beliefs as those that wrote it and I don’t have to think that everything that is written in it actually happened. Aslan, treats the New Testament in much the same way, not just studying the text itself, but also exploring the societies and historical events that frame their construction. While Aslan’s book enabled me to look at Jesus with fresh eyes and provided an interesting perspective, it didn’t describe a Jesus who significantly inspired me. Agreeing with all of Aslan’s conclusions felt unimportant compared to the process of exploration that he provided.

Spong’s book, on the other hand, did present me with an inspirational figure. Like Aslan, Spong also considers historical evidence for Jesus’s life and the formation of the books of the New Testament, but his focus is very different. In many ways, it’s an account of how he, as a Bishop and long standing Christian who can no longer adhere to mainstream Church teachings, has struggled and succeeded in maintaining his meaningful experience of Jesus and God. The Jesus he presents is (very roughly) a first century Jew whose radical activities and high levels of humanity, love and integration were able to inspire similar attributes in those that knew him and those that came to know the versions of him that existed after his death. Spong describes a Jesus that is able to inspire a deeper level of human experience; an integrated state that he calls the ‘God experience in Jesus’. For me, as someone who has no attachment to the idea of God, I would not describe such an experience in those terms. Nonetheless, a combination of my experiences with this society (especially Roberts explorations of inspirational integrated Christian figures such as St. Francis of Assisi) and the reading of these two books has allowed me to reassess and come to understand how one could experience and describe a ‘Jesus experience’ of integration, regardless of background or faith.

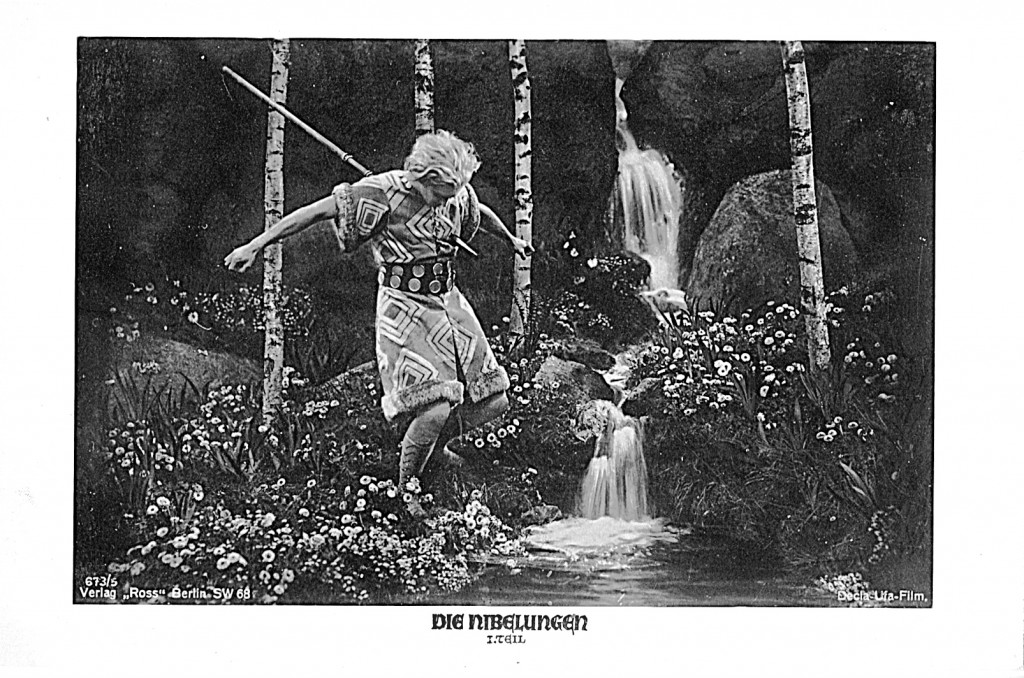

I haven’t had such an experience, but I’m now able to experience Jesus as a figure of inspiration alongside others, such as Julian of Norwich, Albert Einstein, Nelson Mandela or Malala Yousafzai. Another unexpected consequence is that my various Buddha figures have taken on additional meaning: instead of representing only the Buddha, the statues now seem able to represent all those who I find inspirational and who also appear to have experienced high levels of integration. For some, the historical existence of these characters, and others like them will have little impact on their relationship with them. For me, confident historical speculation seems to augment my experience with deeper levels of meaning. I have got no idea if the story of Jesus washing Peters feet (depicted above) represents something that happened but I still find it inspirational. If, however, evidence was discovered that increased my confidence in its historicity then the inspiration and meaning I experience would be further enhanced.