Carl Jung’s Red Book contains an extraordinary personal account of engagement with archetypal figures in a series of induced visions. Robert M. Ellis, who has a forthcoming book on the subject, explains how it can also be an inspiring resource for the Middle Way. This talk was given on Zoom on 19th April 2020, as part of the Virtual Festival of the Middle Way. It is followed by questions from the audience.

Category Archives: Myth

Double Vision

When we try to think critically and to open our imaginations at the same time, a kind of double vision results. At one and the same time we develop our awareness of potential alternatives, making our thinking more flexible, but still remain aware of the limitations of our beliefs, and do not allow our imaginativeness to slip into credulity. We develop meaning but also control belief. It seems to me that developing this double vision is one of the hardest parts of the practice of the Middle Way: but if we are to avoid absolutizing our beliefs we need to develop both meaning and belief. Those of an artistic disposition will find it easier to imagine, and those of a scientific disposition to limit their beliefs to those that can be justified by evidence: but to hold both together? That’s the challenge.

I’ve been reflecting more on the metaphor of double vision, since I heard it used recently in a talk by Jeremy Naydler in the context of the Jung Lectures in Bristol. Naydler used this metaphor in a talk called ‘The Inner Beloved’, which was about the way in which visionary men of the past have maintained images of beloved women that were actually projections of their own psyches (what Jung would call the anima). He spoke of Dante’s vision of Beatrice in the Divine Comedy and Boethius’s figure of Philosophia in The Consolations of Philosophy. These were not ‘real’ women, or had the slightest of relationships to real women, but rather became powerful archetypal symbols of the part of themselves that remained unintegrated. They were the focus of yearning, but also the path of sublimated wisdom – never possessed but always beckoning and challenging.

The capacity for double vision is central if one is to cultivate such a figure: for if a man were to project it onto a real woman (or vice-versa) the results could be (and often are)disastrous. “Being put on a pedestal” probably creates conflict when the real person starts behaving differently from the idealisation – for example, needing time of her own away from a relationship. It is only by maintaining a critical sense of how the mixed up, complex people and things in our experience are not perfect and do not actually embody our idealised projections that we can also give ourselves an imaginative space to engage with the archetype itself. Recognising that the archetype puts us in touch with meaningful potentials, showing us how we could be ourselves, and how we could relate to the world, can provide a source of rich inspiration that I see as lying at the heart of what religions and artistic traditions can positively offer us without absolute belief.

The annunciation, a Christian artistic motif that I’ve previously written about on this site, for me offers an example of the archetypal in its own terms. For most of us, it is much easier to look for the archetypes in art, and separate this mentally from trying to develop balanced justified beliefs with the real people we meet every day, rather than prematurely over-stretching our capacity to separate them by risking archetypal relationships with real people. That’s why lasting romantic relationships need to be based on realistic appraisal rather than seeing the eternal feminine or masculine in your partner, and also why venerating living religious teachers like gods may be asking for trouble.

Personally, I do have some sense of that double vision in my life. My imaginative sense and relationship to the archetypes has developed from my relationship to two different religious traditions (Buddhism and Christianity) as well as from the arts and an appreciation of Jungian approaches. On the other hand, my love of philosophy and psychology provide a constant critical perspective which also provide me with a respect for evidence and a sense of the importance of the limitations we must apply to practical judgement. Sometimes I find myself veering a little too far in one direction or the other, slipping towards single vision rather than double vision, and then I need to correct my course. Too much concentration on cognitive matters can make my experience too dry and intellectual. Underlying emotions and bodily states can then come as an unpleasant surprise. On the other hand too much imagination without critical awareness can reduce my practical resources in other ways, as my beliefs become less adequate to the circumstances.

Our educational system overwhelmingly only supports a single vision, with the separation of the STEM subjects on the one hand from arts and humanities on the other. But a single vision seems to me an impoverished one, even within the terms of that vision. Those with a single vision based on scientific training and values tend to have some understanding of critical thinking, but to think critically with more thoroughness it’s essential to be aware of your own assumptions and be willing to question them – which requires the ability to imagine alternatives. There are also those with a single vision who are willing to imagine, but tend to take the symbolic realm as in some sense a key to ‘knowledge’ of ‘reality’, and thus uncritically adopt beliefs that they can link with their imaginative values. For example, those who, like Jung, find astrology a fascinating study of meaning, often seem to fail to draw a critical line when it comes to believing the predictions of astrology – for which there is no justification.

If it is not simply a product of limited education or experience, a single vision is likely to be associated with absolutisation; because absolutisation, being the state of holding a belief as the only alternative to its negation, excludes alternatives. We avoid allowing ourselves to enter the world of the other kind of vision, then, by regarding ours as the only source of truth, and by disparaging and dismissing the other as ‘woo’ (from the scientific side) or as soulless nerds (from the imaginative). Rather than accepting that we need to develop the other kind of vision, we often just construct a world where only our kind of vision is required. Then we share it with others on social media and produce another type of echo chamber – alongside those created by class, region, educational level, or political belief.

Developing a double vision, then, is an important part of cultivating the Middle Way, and thus also a vital way beyond actual or potential conflicts. A failure to recognise your projection onto someone, for example, creates one kind of conflict, but a failure to imagine may take all the energy out of it and lead to another type of division between you. We may not be able to develop double vision all at once, and it’s best not to over-stretch our capacity for it, but the counter-balancing path is open to you right now from here. Here are some follow-on suggestions on this site: if you’re a soulless nerd, go to my blogs about Jung’s Red Book. If you’re more of credulous “woo” person, try my critical thinking blogs.

Pictures (both public domain): double vision from the US air force and Simone Martini’s ‘Annunciation’.

Order, disorder, reorder

It’s almost a simplistic metaphor, but … picture three boxes: order, disorder, reorder. … [I]f you read the great myths of the world and the great religions, that’s the normal path of transformation.

–Richard Rohr

The words above are taken from a recent On Being podcast, where the host Krista Tippett interviewed the American Franciscan friar Richard Rohr. I’m not one for listening to religious programming, given my leanings towards the non-dogmatic and agnostic Middle Way, but I’ve found that this weekly series hosts a variety of guests with a range of beliefs, from diverse backgrounds and traditions. Krista Tippett, as host, guides the discussions in such a way that the conversations are always mature, nuanced, and tolerant of ambiguity – truly conversations rather than sycophantic platform-building or antagonistic arguments. Furthermore Richard Rohr described himself as being “on the edge of the inside” of traditional Catholicism, pushing at the boundary of Christianity in a very liberal, mystical way.

While I was listening yesterday to the episode featuring Richard Rohr (and I recommend listening to the full ‘unedited’ version of the conversation rather than the 50-minute ‘produced’ show) many interesting facets revealed themselves, but I was particularly intrigued to hear about his “three box” metaphor for the path of adult spiritual development. I understand that in his 2012 book Falling Upward he further explores the idea of the two halves of life, intending to show that those who have fallen, failed, or gone down in their spiritual progress are the only ones who understand ‘up’. However, I’ve not read that book(!) and what I’m going to discuss here is based on what I heard during a part of the interview with Krista Tippett.

While I was listening yesterday to the episode featuring Richard Rohr (and I recommend listening to the full ‘unedited’ version of the conversation rather than the 50-minute ‘produced’ show) many interesting facets revealed themselves, but I was particularly intrigued to hear about his “three box” metaphor for the path of adult spiritual development. I understand that in his 2012 book Falling Upward he further explores the idea of the two halves of life, intending to show that those who have fallen, failed, or gone down in their spiritual progress are the only ones who understand ‘up’. However, I’ve not read that book(!) and what I’m going to discuss here is based on what I heard during a part of the interview with Krista Tippett.

As it is rather lengthy, I’ve split this discussion into three separate blog posts: in this, the first, I discuss the synthetic metaphorical three box model in the context of a well-known a modern myth. In the next (second) post I will consider how Rohr’s three box model might be usefully applied to political polarisation in society. In the third and final blog post I will frame my own ‘spiritual’ development in terms of Rohr’s model.

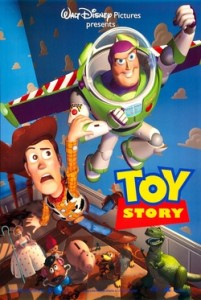

A modern myth – Toy Story

Now, I’m not sure to what extent the Disney/Pixar film Toy Story counts as a great myth of the world, but it’s a story that’s familiar to anyone in the Western world who has grown up – or has had children grow up – in the past 30 years. I have a soft spot for it, having it watched it first (somewhat guiltily) in the cinema as an 18-year old, and more recently on DVD with my son and his cousins. I’m going to use the plot of Toy Story as an example of this “three box” metaphor for the path of transformation – and note that I’m using the term ‘myth’ its original sense as a story richly imbued with archetypical meaning, and not meaning a widely-believed falsehood.

Anyway, in Toy Story the character Woody, the old-fashioned pull-string cowboy doll, starts off in the metaphorical “order box” as Andy’s favourite toy, de facto leader of all Andy’s toys, and comfortable with his position in this microcosm. He is forced into the “disorder box” by the arrival of Buzz Lightyear, the astronaut action figure, who upsets the social order and brings out feelings and behaviour in Woody that he’s not had to deal with before. This disorder is a product of circumstances beyond Woody’s control: he wouldn’t have deliberately chosen to break with the status quo as he was so comfortable within it. His sense of self-esteem is closely linked with his role as Andy’s favourite plaything.

Anyway, in Toy Story the character Woody, the old-fashioned pull-string cowboy doll, starts off in the metaphorical “order box” as Andy’s favourite toy, de facto leader of all Andy’s toys, and comfortable with his position in this microcosm. He is forced into the “disorder box” by the arrival of Buzz Lightyear, the astronaut action figure, who upsets the social order and brings out feelings and behaviour in Woody that he’s not had to deal with before. This disorder is a product of circumstances beyond Woody’s control: he wouldn’t have deliberately chosen to break with the status quo as he was so comfortable within it. His sense of self-esteem is closely linked with his role as Andy’s favourite plaything.

However, through the messy process of being taken out of his comfort zone and learning through novel experiences, Woody eventually is able to move into the metaphorical “re-order” box by integrating his conflicting desires and meaning, establishing a new equilibrium where he and Buzz can cooperate in their roles as Andy’s ‘favourite toys’. However, and more importantly, Buzz and Woody also enjoy the new meaning and richness that comes from their relationship with each other, a relationship that has value beyond their existence as playthings for a child.

By the end of the film Woody has developed a new perspective on his existence, one that encompasses the need for constructed order and the inevitability of uncomfortable disorder – he knows that suffering is part of the deal, and is better embraced than pushed away. Not only is Woody now wiser, but his new worldview better addresses the changing conditions, as Andy is growing up (as seen in the sequels, particularly Toy Story 3) and will no longer ‘need’ Woody, depriving him of his original raison d’etre when he was comfortably housed in the “order” box.

Note that, alongside Woody’s development, Buzz follows a parallel path of transformation. His original existence – where he truly believed himself to be a space ranger crash-landed on a hostile alien planet – may have been delusional, but it was well and truly ordered. He had a sense of who he was, what his mission was, and was confident in his superiority and rightness. Only when his delusion was eroded by continued contact with the ‘real’ world did he have to face up to disorder. Buzz’s fall from order was harsh, but he made progress through the disorder and – by uniting with Woody against common enemies – he was able to reorder his worldview into something more mature mature, integrating his love of himself with his newfound love for others (as opposed to his earlier ‘duty’ to others).

At the close of this first installment in the series I invite you to participate using the comments section below. If you can see how this model can be further extended to Toy Story, or other myths, please go ahead and share your thoughts. If you can see limitation of this model in this context of analysing mythic narratives then please also jump in. In the second installment I will move on to consider how the order-reorder-disorder model might shed some light on the problem of political polarisation in society, and in the third and final installment I’ll be viewing my own spiritual biography through the lens of this model. I hope that you will join me there…

- Continue to Order, disorder, reorder – Part 2…

- Jump ahead to Order, disorder, reorder – Part 3

Featured image of US mailboxes in the snow courtesy of pixabay.com

Photograph of Richard Rohr by Svobodat [License: CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The Toy Story image is a low resolution version of the Disney-copyright poster, used for illustration only under ‘fair use’

Rethinking saintly miracles

Though I’m now trying to give up the common practice of using ‘myth’ to mean falsity, I must also confess to having long used the term ‘hagiography’ (which means the written life of a saint) pejoratively, to mean a one-sided adulatory biography. Both these usages, though, tend to reduce meaningful symbolic material to claims about facts, when their chief significance doesn’t consist in anything of that kind.

Recently I’ve been rethinking my assumptions about hagiography when reading the Life of St. Cuthbert by the Venerable Bede. Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon saint from Northumbria in north east England, closely associated with the holy island of Lindisfarne, and Bede is the scholarly monastic writer of the early eighth century, better known for his ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicles’, though he wrote in Insular Latin (the weird form of Latin we used to use on these benighted islands). In his youth, though, Bede knew and served Cuthbert. Though he claims to have composed it only on the basis of reliable testimony, Bede’s life of Cuthbert is just one damned miracle after another. He cures the sick all over the place. An eagle brings him food in the wilderness. His incorruptible corpse cures the sick too. And when ravens steal straw from the roof of his island hermitage, he banishes them until they come back and apologise, with “feathers outspread and wings bowed low”. What are we to make of all this?

For me this is another opportunity to apply the thinking I’ve been developing in my book The Christian Middle Way (which I’ve drafted and am now hawking around publishers), where I thought about the interpretation of Jesus’ miracles in the New Testament. As regards factual claims about miracles, I’ve long accepted Hume’s argument that accounts of miracles are more likely to be mistaken than otherwise, given that our other experience shows them to be extremely unlikely. Though the probabilities are against the correctness of miracles literally interpreted, we really don’t know. We can speculate about what ‘really happened’ and construct alternative explanations, but this is all likely to be a distraction from appreciation of the meaning of the stories about what happened. That meaning does not depend in any way on what ‘really happened’, but is rather a product of the ways in which the stories reflect the archetypal functions of individuals in the context of a particular culture’s interpretation of those archetypes.

St. Cuthbert’s miracles can be more deeply appreciated if one lets go of the factual questions and focuses only on these archetypes. To illustrate this, let’s start with the healing miracles. Here’s a fairly typical example:

One day, as he was going round the diocese giving saving counsel in all the houses and hamlets of the countryside, and laying his hand on the newly baptised so that the grace of the Holy Spirit might come down upon them, he came to the house of a member of the royal bodyguard whose wife lay ill and seemed to be dying. The man ran to meet him, knelt down and thanked God that he had come, brought him into the house, and made him most welcome…. Then the man told him that his wife was desperately ill and begged him to bless some holy water to sprinkle on her.

‘I am sure,’ he said, ‘God will grant her a speedy recovery, or if she must die, put an end to her long agony and take her without delay.’

Cuthbert had water brought, blessed it, and gave it to a priest to sprinkle over the sick woman. The priest entered her bedroom and found her lying there looking like a corpse. He sprinkled the bed, sprinkled her, opened her mouth, and poured a little of the life-giving draught down her throat. The patient was quite unaware of what was being done, but as soon as the water touched her an astonishing thing happened: she was immediately restored to full health both of body and mind. She came to, blessed and thanked the Lord for deigning to send such guests to cure her, and then, rising from her bed, ministered to those who had just ministered to her, the patient tending the physicians. (ch.29)

Let’s first note the context in which the healing took place. Cuthbert is laying hands on people to give them the grace of the Holy Spirit. The ‘Holy Spirit’ has become such a stock phrase in Christianity that it might seem almost meaningless, a dead concept, but the live meaning of it in experience is probably more about people recognising new possibilities and extending their awareness in ways that also lift up and broaden their emotions, symbolically related to the confidence expressed in the baptism ceremony. Cuthbert is making people aware of the possibility of new integration.

Note then also that when Cuthbert comes to the dying woman, he does not claim to have power over her illness. It is God who kills or cures, not him. ‘God’ here is also a way of talking about the conditions and reconciling people to them. If the woman had died we would presumably not have heard about this miracle, so the story of her recovery may just reflect confirmation bias, coincidence, selective interpretation and the placebo effect: but in the context, Cuthbert focuses our attention on acceptance of the outcome, helping people to adapt to the conditions, whatever they turn out to be.

In that context, like any other healer, he also demonstrates compassion. This compassion is inevitably selective, because he is human and cannot heal everyone. The story thus does not tell us about God’s justice, but rather helps to reconcile us to his selectiveness. Some will live and others die, and the causes of them doing so are very complex and beyond full human understanding. Yet at the same time an intervention that offers renewed confidence for the suffering person may produce a breakthrough, which can then be recorded and inspire others to similar confidence and openness to integration.

Finally, there is also the actions of the woman after her miraculous recovery. Again, this should probably not be taken literally, as in that case it might seem both medically questionable (she would need time to recuperate) and patriarchal (her service to men couldn’t even be interrupted by near-death!). What I find striking about it is the way it deliberately challenges our expectations. Who is sick and who is well? We attach these labels to people, but the conditions are often more complex. Those who have been ill often remark on this problem: that others don’t know quite how to treat them and are unsure about what they can or cannot be reasonably asked to do. They are shoved either into the indulgent category of convalescent or the negative one of malingerer, because we have trouble with coming to terms with the incrementality of health and have to turn it into black and white terms. Miraculous healing makes all things possible, and its function is to make us aware and appreciative of what is possible, and the ways we might be otherwise constrained by our expectations.

Just as in the life of Jesus, so in Cuthbert there are both ‘healing miracles’ and ‘nature miracles’ in which the saint is depicted as being able to participate in God’s control over nature. The following story can illustrate this other type of miracle, and again it is important to quote some of the context.

Not only the inhabitants of the air and ocean but the sea itself… showed respect for the venerable old man. No wonder: it is hardly strange that the rest of creation should obey the wishes and commands of a man who has dedicated himself with complete sincerity to the Lord’s service. We, on the other hand, often lose that dominion over creation which is ours by right through neglecting to serve its Creator. The very sea, I say, was quick to lend him aid when he needed it.

He set about constructing within the walls of his dwelling a small shed which should be big enough for his day to day requirements. It was to be built towards the sea with the floor over a long deep cleft hollowed out by the constant action of the waves. It was to be twelve feet long, for that was the length of the cleft, so he asked the monks to bring him some planks of that length for floorboards the next time they came. They willingly agreed, received his blessing, went off home and forgot all about it. Back they came on the appointed day but without the wood. He gave them a very warm welcome, commending them to god with the usual prayer, then asked ‘Where is the wood?’ Then they remembered. They confessed they had forgotten and asked him to pardon their negligence. The kindly old man soothed their anxiety with a gentle word and bade them stay till next morning: ‘For I do not believe God will forget my wish’. They complied with his request. The following morning when they went out there was a piece of wood of the correct length thrown up by the tide right under the site of the shed. They marvelled at the sanctity of a man whom the very elements obeyed, and blushed with shame at their own slackness in needing to be reminded by inanimate nature what obedience is due to saints. (ch. 21)

‘Coincidence’, I think, as you probably do too. But we don’t know whether or not it should be rightly described in such a way. What the story records, however, is the meaning of these events for the participants. The monks interpreted the driftwood as a divine rebuke because they were ashamed of their negligence, so for them it served the purpose of symbolising their limited awareness and its consequences, regardless of whether or not the driftwood was the result of supernatural intervention. Cuthbert, however, did not offer such a rebuke but responded kindly, presumably in awareness that the monks’ integration (and thus their remembrance of others’ needs in future) would be better supported by such kindness.

Where Bede sees creation as serving the servant of God, we can see a person who is integrated enough to have fully adapted to his environment, recognising both what he can and cannot do in it. He can make use of one piece of driftwood, but since he asked for ‘planks’ he presumably still needs more than this for his building project. He accepts those conditions that he has no power over, but makes the most of those that he can affect. He is emotionally as well as cognitively adapted, not just resourceful but also flexible in his expectations. Read helpfully, then, this story is not about power over nature at all, but about the balanced acceptance of our lack of power. Our ‘dominion over nature’ is only ours by right when we serve its creator: meaning that we only get what we want by recognising the full extent of the contrary conditions. Today, the belief in ‘dominion over nature’ has been blamed by thinkers like Peter Singer for the attitudes that created anthropogenic climate change, but if that belief had been better tempered by awareness and respect for conditions we would have been much readier to accept our role and its effects at an earlier stage when we could do more to prevent it.

So, miracle stories, read carefully with an eye for their meaning in context, can offer us inspiration rather than falsehood. I am not suggesting that this is what they ‘really mean’: rather that we can usefully choose to interpret them in this way – the Middle Way that avoids the reductions of presumed truth or falsehood. Hagiography of a more traditional kind thus takes on a new meaning. However little I learnt about the faults and shadows of the historical Cuthbert from Bede’s biography, I at least found some inspiring reminders of the meaningful wisdom of the past. I don’t take that as a justification for writing such hagiographies today, because it is more important for us to develop balanced beliefs about more recent lives. But Cuthbert for me, and probably for you, is much more of an archetype than a historical figure. The Anglo-Saxon world offers a distance that makes such symbolic power possible.

Picture: St Cuthbert Praying from Bede’s manuscript: British Library Yates Thompson MS 26. Reproduced for comment under fair use terms.

Quotations from Bede’s Life of Cuthbert come from ‘The Age of Bede’ trans J.F. Webb, pub. Penguin Classics. Reproduced for comment under fair use terms.

Links to some related posts:

Video: separating absolute belief from archetypal meaning

Audio talks on archetypes (scroll down)

Finding Jesus (perhaps that hole isn’t God shaped after all)

My relationship with Jesus of Nazareth has recently changed for the better. I’ve never felt particularity negatively towards him, as I have towards God (I just can’t respond well to a character who encourages filicide, slavery, bigotry and genocide, to satisfy their own jealous insecurities) and have always found his depiction to be strangely captivating. Yet I have not consciously regarded him as a figure of inspiration; I always felt that he was the property of practising Christians, and anyway, wasn’t he the Son and earthly manifestation of the God that I find so problematic? This, I am pleased to report, is no longer representative of how I feel (about Jesus, at least) and I’d like to spend some time explaining how this change of heart has come to pass.

As the assumed Son (and earthly manifestation) of a perfect God, it has always been posited to me that Jesus must also be perfect; this was either something you believed in or you didn’t, take this view of Jesus or don’t take him at all. I assumed that as there are compelling arguments to suggest that the Abrahamic God is far from perfect, then it must also follow that Jesus could not be perfect. Further confirming this view, a recent reading of the New Testament revealed a sometimes flawed and aggressive Christ rather than the serene, unshakably tolerant, haloed figure of Christian tradition. This Biblical character seemed leagues apart from the perfect Jesus that I’d been taught about, through art and carefully selected Bible readings. I also had the suspicion that even if I did find inspiration in Jesus, I could not do so openly and easily without belief in God – as an atheist (hard agnostic) I have often been asked (sometimes forcefully) why I celebrate Christmas, and the fact that my wife and I were married, as atheists, in our local parish Church has also caused confusion and even offence. When I considered all of this alongside the glaring inconsistencies in the New Testament my response was one of rejection.

In the past year or so I have read two books that have caused me to think again: Zealot by Reza Aslan and Jesus for the Non-Religious by John Shelby Spong. Although I discuss them here, this is by no means supposed to be a detailed analysis or synopsis. I would, however, recommend them both for reading. Aslan spends a lot of time exploring the historical context of Jesus’ life and of the subsequent writing of the books of the New Testament. I think he does this well and draws many interesting conclusions. The main one being that Jesus was a radical Jew who, as part of a wider movement, challenged the authority of Rome and perceived corruption of the priestly class, and despite being unsuccessful had a profound impact on those that followed him. In the decades after Jesus’s death and in the wake of the Roman’s retaliatory destruction of Jerusalem (following their successful expulsion), the foundations of the Christian church were laid – by some that knew him and by many that did not. Interesting as they are, such conclusions were not the most affecting aspect of my time with this book. Rather, by thinking about Jesus as a human being and the New Testament as a series of documents – both worthy of historical analysis and set within a surprisingly (for me at least) well understood historical context, I found that my entrenched rejection began to subside. The fact that Jesus might have existed (and I think it seems likely that he did, given the short time in which his cult developed following his death) and that I felt able to explore this possibility, without feeling that I should harbour some sort of Christian belief, has become fundamental to the way I am able to engage with him and the texts in which he appears.

One can argue, rather successfully as it happens, that to be inspired by Jesus’s life and message requires neither Christian belief nor interest in the historical figure. I agree, to an extent; why should one have to suspect that Jesus existed to respond positively to his message of forgiveness? One doesn’t. Nonetheless, by doing so I have been able to attain much more meaning from the Jesus story than I could before. Why then, should it matter if individuals or events can be argued to be historical in relation to the meaning they have for me?

Take the image of Father Christmas. I’ve long believed that the red and white colour scheme of his outfit was designed and introduced by Coca-Cola as part of a marketing campaign. Red and white are the identifying colours of the company and they do have an irritating habit of plastering Santa’s image over a massive articulated lorry that appears on their festive adverts and visits various towns and cities. It came to my town this year and people went wild, standing round it in large crowds staring excitedly – filming it on their mobile devices, no doubt. Anyway, this association with a) the advertising industry and b) a multi-national company, that has a rather chequered ethical reputation, tarnished the meaning of images of Father Christmas for me. I still had fond memories of childhood, of family getting together in merriment, of nativity plays, of Christmas smells (the list goes on) – but they were mixed up with notions of cynicism, commercialism and exploitation of communities in the developing world. Of course, the whole Christmas season involves these things, it is a time of excessive contradictions, but the idea of this treasured figure from my childhood being the cynical marketing construction of a company that I have had ethical concerns about distilled this somehow. Thus, I was quite delighted to find out that the story is probably not true. Yes, Santa’s image is widely used for cynical marketing purposes, but the fact that his traditional image is used, rather than having been created for, this purpose seems to matter to me. The story of Coca-Cola creating Father Christmas’s modern image still exists, but the knowledge that it is likely a misconception, rather than historical event changes, for me, the nature of its meaning, and the meaning of depictions of Santa.

Walter White and the series Breaking Bad provide another example of how confidence in the historicity of events can impact on the meaning they may have on an individual. I loved Breaking Bad; I didn’t want to, because of its popularity, but I did. The series is harrowing in places and the actions of White become increasingly extreme and difficult to justify. It skilfully explores a wide range of ethical issues, and I often found myself questioning not only the characters, but myself. However, if I’m honest, I was always on the side of White. No matter what he did, I was with him all the way. Now, if I ‘d gone into the series with the belief (or found out after) that it was either a biography based on actual events, or that it was a documentary, I would have had a very different response to White and his activities. The ethical questions would still be there, as would the wonderful grey morality in which the story revels, but my response, both intellectual and emotional would be very different; White and his story would have had different meanings for me.

By thinking about Jesus without personal associations of Christian dogma, I’ve been able to imagine, with varying degrees of confidence an individual of greater scope and depth. This does not require a separation of Jesus from either Jewish or Christian belief. Nobody seems to quarrel when historians study Alfred the Great or Joan of Arc. Both individuals were pious Christians, both have mythologies that blur the lines between history and fiction, and one does not have to share their beliefs to study or take inspiration from them. It seems acceptable, in a way that it often isn’t with Jesus, to examine the evidence and conclude with a degree of confidence that each of these figures existed and that some life events are more likely to have occurred than others. Joan of Arc (like most historical figures) is both a figure of mythology and of history, there is no conflict and the lines between the two need not be distinct. If I consider the possibility of Jesus as the radical reformative Jew described above and then take a hard-agnostic view on the possibility of him being the Son of God (whether he thought he was or not is often debated, but there is at least the possibility of finding historical evidence) then Jesus ceases to be perfect, and this is a good thing. Apart from being more interesting, his sometimes erratic and even intolerant behaviour becomes less problematic. As a human in a specific historical context, he can be excused for being imperfect, or even morally questionable in a way that God cannot. The New Testament can be similarly viewed. Even more than Jesus (who is not around today), the Bible has a history, its various books can be placed, with varying degrees of accuracy, within historical times and places. The authors need not be identified to understand the context in which they were written. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle is a vast document that details events over a long period. It’s often contradictory and seems to freely mix fiction with historical events and yet it’s place as an important historical document is rarely questioned. I don’t have to have the same beliefs as those that wrote it and I don’t have to think that everything that is written in it actually happened. Aslan, treats the New Testament in much the same way, not just studying the text itself, but also exploring the societies and historical events that frame their construction. While Aslan’s book enabled me to look at Jesus with fresh eyes and provided an interesting perspective, it didn’t describe a Jesus who significantly inspired me. Agreeing with all of Aslan’s conclusions felt unimportant compared to the process of exploration that he provided.

Spong’s book, on the other hand, did present me with an inspirational figure. Like Aslan, Spong also considers historical evidence for Jesus’s life and the formation of the books of the New Testament, but his focus is very different. In many ways, it’s an account of how he, as a Bishop and long standing Christian who can no longer adhere to mainstream Church teachings, has struggled and succeeded in maintaining his meaningful experience of Jesus and God. The Jesus he presents is (very roughly) a first century Jew whose radical activities and high levels of humanity, love and integration were able to inspire similar attributes in those that knew him and those that came to know the versions of him that existed after his death. Spong describes a Jesus that is able to inspire a deeper level of human experience; an integrated state that he calls the ‘God experience in Jesus’. For me, as someone who has no attachment to the idea of God, I would not describe such an experience in those terms. Nonetheless, a combination of my experiences with this society (especially Roberts explorations of inspirational integrated Christian figures such as St. Francis of Assisi) and the reading of these two books has allowed me to reassess and come to understand how one could experience and describe a ‘Jesus experience’ of integration, regardless of background or faith.

I haven’t had such an experience, but I’m now able to experience Jesus as a figure of inspiration alongside others, such as Julian of Norwich, Albert Einstein, Nelson Mandela or Malala Yousafzai. Another unexpected consequence is that my various Buddha figures have taken on additional meaning: instead of representing only the Buddha, the statues now seem able to represent all those who I find inspirational and who also appear to have experienced high levels of integration. For some, the historical existence of these characters, and others like them will have little impact on their relationship with them. For me, confident historical speculation seems to augment my experience with deeper levels of meaning. I have got no idea if the story of Jesus washing Peters feet (depicted above) represents something that happened but I still find it inspirational. If, however, evidence was discovered that increased my confidence in its historicity then the inspiration and meaning I experience would be further enhanced.