Here is Robert M. Ellis’s recent talk on the Christian Middle Way at the Virtual Festival of the Middle Way, 18th-19th April 2020, (followed by discussion). His powerpoint can also be downloaded.

Category Archives: Middle Way Philosophy

Introduction: what is the Middle Way

Here is the edited video from the first session of the Virtual Festival of the Middle Way: What is the Middle Way? There is also a copy of the powerpoint and saved chat.

Cutting the Gordian Knot

The ability to cut through complexity and reach a simple resolution has an obvious appeal, yet ‘shortcuts’ can also be very damaging because they fail to engage with complexity. Are shortcuts always absolutisations? The story of Alexander the Great cutting through the Gordian Knot has always appealed to me. Here were lots of people arguing with endless complexity about how to untie the knot, and Alexander saw intuitively that all this complexity was unnecessary and unhelpful – so he cut the knot! Can this be justified?

I think it can. Absolutisations are always shortcuts, but shortcuts are not always absolutisations. Sometimes shortcuts are the best practical response to a situation in which continuing to try to address complexity is just creating more and more loops of conflict. Endless complex debate can also reinforce a certain limited framework within which a problem is being understood, with the boundaries strangely being reinforced by the complexity of discussion. Complexity is always there, and things are indeed likely to be more complex than we recognise, but that does not necessarily imply that a response that tries to limitlessly deal with complexity is the best one for us as agents within that system.

Alternative examples to Alexander cutting the Gordian Know can be found everywhere. For example, I think that agnosticism about God is a good example. The ramifications of theological debate about God’s ‘existence’ are endless, but their complexity depends on particular conceptual assumptions that do not actually help us address the complexity of conditions. Cutting the Gordian Knot here means pointing out that it’s totally irrelevant to our experience of phenomena (including religious experience), and of value, whether or not God ‘exists’ as a supernatural entity. The obsession with God’s ‘existence’ consists of a set of assumptions that we can simply cast aside. As long as we are caught up in the complexity of the arguments, that approach seems unthinkable, until one moment when it simply occurs to us that we don’t actually have to take a position on all of this. We can cast the burden aside and walk free.

But how can we tell when it’s justifiable to cut a Gordian Knot, rather than try to face up to complexity? I’d suggest that the key test is not about complexity at all, but about whether we’re facing up to alternatives. If we are offered alternatives that we simply ignore or dismiss because they are ‘off the map’ (not because of a reasonable judgement about their credibility), then the chances are that we are absolutizing, whether the alternative we’re ruling out is simple or complex. In the case of agnosticism about God, in most cases agnostics have tried out the arguments about God’s ‘existence’ and found them only productive of conflict, and have then recognised agnosticism as an alternative. Theists and atheists, on the other hand, routinely misunderstand, ignore or dismiss agnosticism: they have not engaged with it as a genuine option. On the other hand, many British attitudes to the EU routinely ignore its complexity, especially by jumping to the conclusion that it is ‘anti-democratic’, without examining the great complexity around the question either of what democracy means, or what it would mean for a supra-national body to be appropriately democratic. In this case, in my view the failure to face up to complexity is also a failure to consider alternatives to the easy view one has adopted, or to break out of the limited assumptions of a particular discourse.

My thoughts on this question have been especially stimulated recently by the Brexit impasse as it is continuing to ramify in the UK. I have taken a great interest in the complexity of these events, and am inclined at times to feel frustrated at the failure of most members of the public to engage with this complexity. However, I’m also beginning to think that one particular simple answer may in practice be the best one: that is, the recently adopted Liberal Democrat policy of simply revoking Article 50 and thus ending the whole Brexit debacle through one parliamentary action. It’s been pointed out to me that this would not be ‘simple’ at all, because it would create a lot of resistance, but this is where we also need to avoid the nirvana fallacy and compare different possible courses of action with each other rather than with an impossible ideal. The UK is deadlocked because there is great resistance to any possible course of action – so the choice seems to be between different actions that would all create great resistance: no-deal, deal, second referendum or revocation. Of these, the first three all threaten to prolong the impasse, because of the contradictions and impracticality in the case for Brexit itself. Only revocation seems to stand a chance of ending it in the long-term: but its simplicity seems to be one of the main barriers. Those who have been trying to engage with the complexity for so long can no longer believe that it might be that simple: just let go!

Part of the problem with discussing this topic also seems to be that people’s assumptions about what is ‘simple’ and what is ‘complex’ vary hugely with their background and perspective. If we are accustomed to dealing with complexity in a certain subject area, our handling of the concepts gets gradually easier, so it no longer seems ‘complex’ to us at all. Things that seem simple in one respect may also be complex in another – as I think is the case with Middle Way Philosophy in general, which is simple in its key idea, but complex in its application. However, we can probably all agree that cutting the Gordian Knot is a relatively simple action compared to trying to untie it. I expect lots of disagreement with my views on the two contentious examples I have used – God and Brexit, but the key point in my view will be not so much whether you are prepared to cut Gordian knots on occasion, but what your approach is to judging those occasions. Can you face up to alternatives, even if those alternatives sometimes seem unacceptably simple rather than unacceptably complex? That is an ongoing practice for everyone.

Picture: Alexander cutting the Gordian Knot by Lorenzo de Ferrari (Wikimedia Commons/ Carlo Dell’Orto CCBYSA 4.0)

Fractal adaptivity

Should the concept of adaptivity (or adaptiveness) not itself be adaptive? In my work on Middle Way Philosophy, I’ve often found myself arguing that a traditional way of thinking about a concept that may have worked in a past context is too restrictive for the present one. Moving on from the limitations of Buddhist ways of thinking of the Middle Way as lying between ‘eternalism’ and ‘nihilism’ is one example of this, and another (that I’m working on for my next book) is the need to move on from Jungian accounts of archetypes as innate features of the ‘collective unconscious’. In both cases, the alternative needs to be a more universal and thoroughly functional account of the concept, helpful to all people in all places rather than tied to a limiting paradigm. We owe a huge debt to the people who developed these concepts, but need to pass on the flame rather than worshipping the conceptual ashes. So it seems, also, with the concept of adaptivity itself, which for many people is strongly tied to a Darwinian paradigm.

In the basic Darwinian view, adaptivity is a matter of the continuing survival and reproduction of an organism in changing conditions. The organism passes on its genes to its descendants with minor mutations, some of which are better adapted to new conditions and others of which are not. ‘Natural selection’ then ensures that the better adapted organisms survive and reproduce, whilst the less well adapted die out. This kind of adaptivity , however, is a relatively crude. It takes a very long time for significant adaptation to occur, only operates at the level of entire species or sub-species, and requires the maladapted to perish in the process. Nevertheless, many thinkers still seem to think of this as the only acceptable understanding of adaptivity. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, for instance, expresses a valuable perspective on the long-term value of our ability to adapt to extreme and unpredictable events, or ‘fat tails’ as he calls them. If our perspective is too short-term, and we fail to take these events into account, even if we appear to be well-adapted to a more limited immediate range of conditions, we lose. However, the kind of adaptiveness he has in mind appears to be only that of survival (even if not strictly only of a species). In this he seems to follow a strand of thinking in evolutionary biology that reduces all other forms of adaptation to that one.

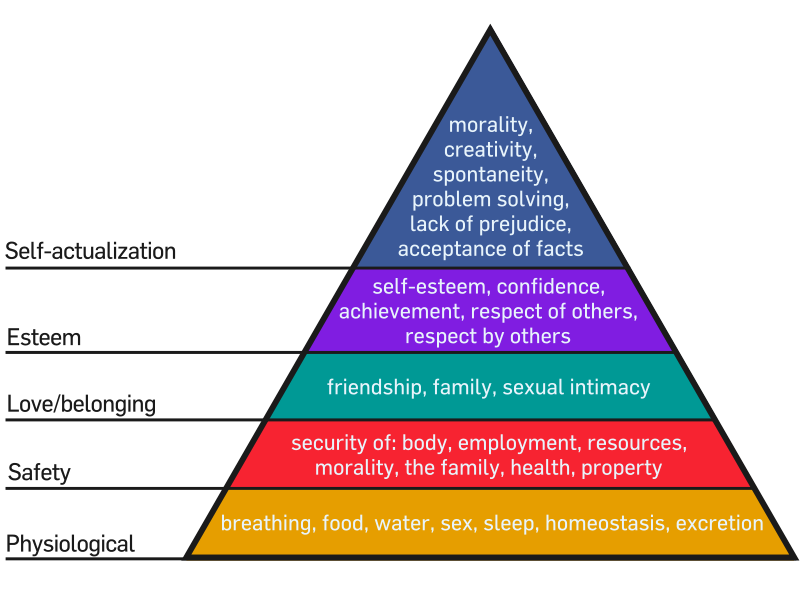

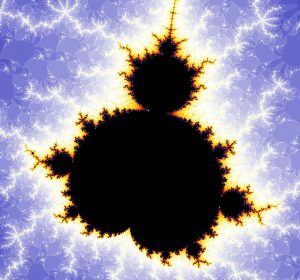

However, adaptation is clearly a much more complex concept than that. It is a feature of a system, and systems may operate at different levels where their goals may not be just the survival of the system (practically necessary though that remains), but rather the fulfilment of a variety of needs. As systems evolve greater complexity, their goals also become more complex. Whilst survival is always the grounding condition on which the development of other goals depends, a hierarchy of ‘higher’ goals can develop in dependence on them. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs expresses those adaptive goals for humans, working up from the social adaptations of belonging and esteem to the individual one of what Maslow called ‘self-actualisation’. But how can we understand Maslow’s insights in the context of adaptation? After all, a reductive evolutionary biologist would probably say that all of these needs boil down to survival in the end, and that even self-actualisation is only adaptive because it helps us solve problems or get on with others in ways that help us survive. I don’t agree that that’s the whole story, though, and it has recently occurred to me that talking in terms of a fractal structure may help to explain the relationships between different types of adaptivity. In a fractal structure, the features of a larger system are reproduced (potentially infinitely) at smaller and smaller scales, the Mandelbrot Set (pictured) being an example of th

But how can we understand Maslow’s insights in the context of adaptation? After all, a reductive evolutionary biologist would probably say that all of these needs boil down to survival in the end, and that even self-actualisation is only adaptive because it helps us solve problems or get on with others in ways that help us survive. I don’t agree that that’s the whole story, though, and it has recently occurred to me that talking in terms of a fractal structure may help to explain the relationships between different types of adaptivity. In a fractal structure, the features of a larger system are reproduced (potentially infinitely) at smaller and smaller scales, the Mandelbrot Set (pictured) being an example of th ese relationships mathematically turned into an image.

ese relationships mathematically turned into an image.

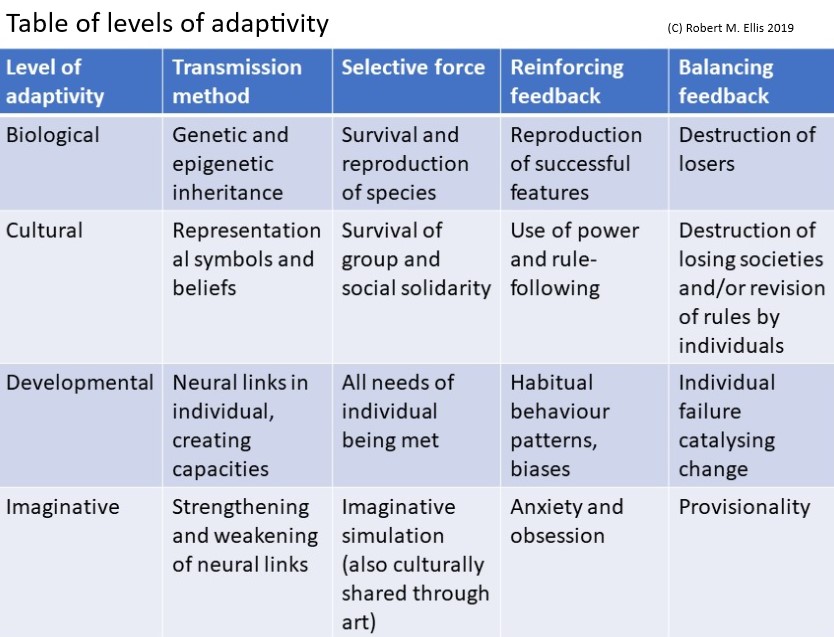

To think of adaptivity in a fractal way, we’ll need to think of a hierarchy of successively smaller systems (smaller both in time and space) dependent on the larger one, but in which the same basic pattern of conditions operates. Exactly how you divide up levels of adaptivity may be a matter of debate, but I think we can distinguish at least four levels: biological, cultural, individual and imaginative. In each case there is a means of transmission of certain features that operates only at that level, a specific selective force that depends on the fulfilment of needs in different conditions, and both reinforcing and balancing types of feedback. I’ve suggested what the features of these four levels might be in the table below, though I’m sure this sketch can be refined.

When we get to the ‘higher’, or more distinctively human, forms of adaptivity, it is our use of symbols to create meaning that seems to be the basis of adaptivity, but operating in three different ways. At a cultural or social level, shared symbols and beliefs help societies to adapt, although rigidity in those symbols and beliefs can also become maladaptive. At this level, safety, belonging and respect start to become important in addition to survival. At an individual level, the development of an individual capacity for meaning and belief through neural links allows that individual to meet all their needs, including self-actualisation. Again, however, rigidity of belief can be maladaptive – this time for the individual. Within the individual, and within a shorter time-frame rather than a whole life, there is finally an imaginative level of adaptivity that is created by our ability to use symbols hypothetically and thus simulate possibilities in our minds. This imaginative process boosts our adaptivity as individuals, helping us to adapt far more quickly than we could do by merely waiting for our previous habits to fail us in new conditions. However, once again, maladaptivity for the individual occurs through the reinforcing feedback of imaginative reconstruction in loops of anxiety or obsession.

I think that these ways of understanding adaptivity help us to distinguish the Middle Way clearly from other kinds of adaptivity to a context. The practice of the Middle Way does not consist in just any kind of balancing feedback loop, but rather the development of awareness required for provisionality. If we can examine alternatives hypothetically, we can not only be freed from reinforcing feedback at the imaginative level, but also start to make an impression on the more basic levels. Provisionality applied consistently and courageously can change both long-term individual development and social beliefs, slow and frustrating though that process may seem when we see our societies going through damaging reinforcing feedback loops. Whether we can successfully influence the biological level is much more debatable.

However refined our thinking as individuals, however, we are still subject to the more basic conditioning of the biological level. As we are increasingly discovering through the climate crisis, the very existence of the more complex and refined systems, both social and individual, is under threat if we cannot maintain the basic conditions for our survival as a species.

Pictures: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs by factoryjoe (Wikimedia Commons). Mandelbrot Set picture of unknown origin. Table of levels of adaptivity by the author.

The New Class Struggle

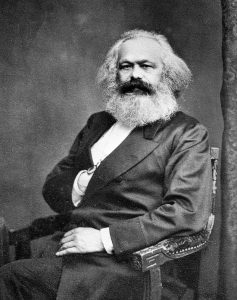

In recent weeks I have been hacking my way through piles of exam papers, particularly featuring a question about Marx. Although this activity generally requires the suppression of all creative impulses in favour of total concentration, I still haven’t managed to stop myself engaging in some reflections about the relevance or otherwise of Marx’s beliefs about class struggle today, and how it all relates to the Middle Way. Now that I’ve finished the marking, I’m finally at sufficient liberty to write down my thoughts.

In ‘The Communist Manifesto’, Marx and Engels famously described the whole of human history as a history of class struggle. In one way or another, they say, the propertied classes have constantly found new ways of exploiting the unpropertied proletariat, in differing circumstances from ancient slavery to the factory floor. However, they go on, capitalism creates such extreme exploitation that eventually the workers “will have nothing to lose but their chains”. Purified by their total exploitation, they will overthrow the bourgeoisie in a revolution, which will usher in a merely temporary dictatorship of the proletariat, followed by the ultimate stability of the communist society.

The elements of dogma in this story are not too hard to identify. The socio-economic determinism is one: Marx’s ‘inevitable’ story shows no signs of turning out quite like that. The purification of the proletariat through suffering is also a projection that seems to have no basis in psychological, let alone historical, conditions. Far from gaining the ultimate wisdom to finally end social and political conflict, people who are suffering acutely tend to get more stressed and more reactive. It’s only if you are very well prepared for your suffering that you might be able to learn from it, but even then it’s unlikely to bring you to an absolute state of moral perfection.

Nevertheless, the power in Marx’s story, fuelling several revolutions, also suggests to me that there must be some insights in it, mixed in with the dogmas. The story that history is a matter of class struggle does seem potent, because it is indeed quite possible to analyse history in that way. More profoundly, though, class struggles are also struggles within individuals, who identify with different sets of beliefs that may either prioritise narrow economic interests or wider values. Those conflicting values also defy resolution because they are framed in absolute terms. When you feel that you have to choose between your job and your conscience, for instance, that is ‘class struggle’ in a the wider sense, whether you are a nineteenth century mill worker or a modern Conservative Member of Parliament. You can focus on class struggle sociologically and ignore the psychology (as Marx did), or you can focus on resolving the psychology of the personal struggle and ignore its political dimension (as in the recent phenomenon of ‘McMindfulness’), but the phenomena you are dealing will have all these dimensions, and the tendency to ignore some of them is an unfortunate result of over-specialisation.

Property can provide powerful vested interests, but vested interest is not the only human motivation, so I cannot agree with Marx’s assumption that the story of class conflict is only about the division between those who have property and those who do not. Instead, it seems to me more powerfully to be between those who absolutise narrow motives (including, but not limited to, property interests) and those who, whilst remaining human and having interests, are capable of thinking provisionally about them and weighing up different values. Ironically enough, those who are capable of doing this quite often have a modest amount of property, which has given them enough security to be able to start thinking provisionally. Those who have no property at all are often (but not always) so insecure that it’s difficult for them to avoid thinking in absolute ways that are constantly fuelled by craving and anxiety. No, the proletariat are not purified by their suffering. Rather their suffering makes them easier for unscrupulous absolutists to exploit.

So what is the class struggle today? Well, we are in the midst of it. The US and the UK particularly are currently wracked by political conflict that seems to have a strong class basis. That political conflict involves ongoing polarised disagreement about climate change, about nationalism, about social justice, about the rights of minorities, and about the role of the state, along with many other associated issues. It’s not a conflict between the property-owning bourgeoisie and the propertyless proletariat though. Rather it’s primarily a conflict between, on the one hand, a cabal of autocrats and billionaires with their numerous stooges, and on the other, middle class intellectuals. Not all members of any particular socio-economic group are necessarily on one side or the other – there are still middle class intellectual climate change denialists, working class internationalists, and billionaire liberals. Nevertheless, the conflicts have a strong class dimension as well as a psychological and philosophical dimension. It would be surprising if they didn’t, given how important social class is to our identity.

The ‘middle class intellectual’ class has not been merely created by material conditions and accompanying vested interests, as Marx would tell us. Rather, they have come to appreciate conditions better, and overcome some of their biases, by having their minds opened in one of a variety of possible ways. University education and professional training provide the most common vectors for it (as shown in Robert Kegan’s work on the contexts for what he calls stage 4 and 5 adult psychological development). Travel, friendship, study, art, and religious experience all provide other possible routes to bigger perspectives that may help to inoculate you against becoming a stooge.

The new propertied exploiters, on the other hand, are defined either by their narrow focus on power and economic advantage, or by other dominant absolute beliefs that facilitate that exploitation (such as religious fundamentalism). The majority of their supporters, though, are subject to what Marx called ‘false consciousness’: that is, they have been influenced into a set of beliefs that are against their own long-term best interests. The sources of false consciousness now come overwhelmingly from media manipulation that can apparently be traced back to autocrats and billionaires, from Fox News to the Daily Mail to Russian troll factories. This media bias chart provides a useful reference of the sources of such manipulation (which are found on left as well as right, but are overwhelmingly weighted towards the right). The strong links between climate change denial, the fossil fuel industry, and right wing politics are also confirmed by a number of academic studies.

In Marx’s analysis, intractable class conflict can come to an end only through violent revolution that breaks the mould of the system. Unfortunately this seems to be another of his delusions, if the evidence of actual revolutions is anything to go by. A revolution may change those in power, but it is unlikely to change the systemic patterns of interaction, which are likely to reassert themselves to a greater or lesser degree (as they did in the Soviet Union). The stakes in our new class conflict, though, are far higher than just the exploitation of one class. The very survival of human civilisation is at stake. The conflict may end in the ‘revolution’ of the destruction of all, or it may be gradually ameliorated through changes in the ways that we respond to conditions. Either way, though, the middle-class intellectuals will evidently prevail in the long-run, just as Marx predicted that the proletariat would prevail, either by being proved right or by running the world their way. That’s not because they’ve been purified or because their perspective is perfect, but rather because they imperfectly recognise that their perspective is imperfect when their opponents do not.

Is this another story as incredible as Marx’s? I think it identifies some of Marx’s insights (class conflict, its intractability, its relationship to ideology, its asymmetry, and the nature of false consciousness) whilst also drawing attention to his dogmas (determinism, absolutisation of vested interest, purification of suffering) and limitations (ignorance of psychology, ignorance of ecology). Marx was concerned, most basically, with how people address conditions, but the ‘science’ with which he interpreted this was heavily loaded with false assumptions. The updated story I’m offering in its place may also be based on some false assumptions, but at least it is based to some degree of recognition of the need to address such assumptions (Marx tended, instead, to say that his story was ‘science’ and everyone else’s was ‘ideology’).

I expect some of the first reactions to that alternative story to be based on false equivalence, which is a common absolutist strategy (think of Trump drawing equivalences between white supremacist demonstrators and their opponents). For an absolutist, everything is dual, and there can be no such thing as better judgement through provisionality. Their opponents are therefore always assumed to be as absolute as they are, and they will insist on reducing all complexity to that equivalence. Incremental marks of credibility (such as expertise, relative lack of vested interest, ability to observe, and corroboration) as well as every kind of evidence and every widely-used value, are ground down by absolutists into the same false equivalence. However, as Marx recognised, the class struggle is asymmetrical. One side is right and the other wrong (even if it’s not always clear who is on each side), because the wrong side is entirely blinded by its assumptions, totally immersed in confirmation bias. We are all subject to confirmation bias, but some of us are facing up to this fact and others are not.

The other objection I am expecting will be to point out a false dichotomy. “It’s not as simple as that,” you may say. “Surely there were not just two conflicting classes in Marx’s day, and there aren’t now either?” I agree. I am only trying to make sense of the idea of “class conflict” by separating out the elements that seem to demonstrably cause conflict from those that are just Marxian dogmas. However, any generalisations we make about “classes”, especially when they involve determinately dividing people up, are fraught with all kinds of complex difficulties. That’s why I only want to define the “classes” in terms of their relationships to absolutisation. Whenever you or I are dominated by absolutisation, we’re in the repressive class, as exploiters or their stooges, even if we’re middle-class intellectuals. If we cease to do so and start to judge provisionally, even if we’re in the pay of Fox News, we cease at least temporarily to be in that exploitative class. We cannot define the classes sociologically in any way that I find remotely satisfactory. The social categories I have used above can only be proxies for psychological ones, and are just ways of pointing out that the psychological conditions do have constant social implications.

Psychologically, too, absolutism is not defined by counter-absolutism, but by its own assumptions. Once again, then, we also see that the Middle Way is not a compromise. If we respond to absolutists with counter-absolutism (as some left-wing absolutists do) we become absolutists. However, if we respond critically but with confident provisionality, we are not being dogmatic. The practice of the Middle Way is provisionality, not compromise, and the confidence with which it needs to be taken up must not be automatically mistaken for dogma. The Middle Way seems to be the only practical solution to the class conflict that so much concerned Marx.