The idea that there is something that a person, an observation, a text or a word ‘really means’ seems to me one of the most undermining of our understanding of conditions around us. It is based on a widespread misunderstanding of meaning itself: that meaning somehow stands beyond our experience and we only have to tap into the ‘true’ meaning. To avoid beliefs about ‘true meaning’ is not to give up confidence in meaning or to believe that any particular thing (let alone the world as a whole) is ‘meaningless’: rather it is to recognise that it is us who experience meaning, in our bodies and their activity.

Here are some examples of the kinds of assumptions people often seem to make about ‘what things really mean’:

A person:

- “What I really meant when I said that was that you look better than you did before. That was a compliment. There’s no need to take offence.”

- “What David Cameron really means when he talks about a ‘big society’ is one where the state is so starved of resources that the poor depend on random acts of charity.”

An observation:

- “What the low level of UK productivity really means is that here can be no long-term or secure economic recovery.”

A text:

- “What the gospels tell us about eternal life really means an experience that goes beyond the ego.”

A word or term:

- “What the Middle Way really means is the Buddha’s teaching of conditionality as an alternative to belief in the eternal self (sassatavada) or extinction of the self at death (ucchedavada).”

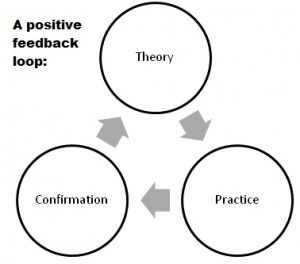

In any of these examples, I’d argue that, of course, we cannot claim that these things are not part of what is meant. Perhaps they are even an important part. Very often, in practice, by appealing to ‘what is really meant’ people just want to offer an alternative to what someone else has assumed. However, the language of ‘really’ is very likely to involve an implicit absolutisation. Against one set of limiting assumptions, we offer the opposite, which tends to entrench us in further limiting assumptions.

At one extreme, this may amount to a seriously misleading straw man, where we give an account of someone else’s view that they would be unlikely to recognise themselves (e.g. the second example above, about David Cameron). At the other, an illuminating new interpretation may be offered that may greatly add to our useful understanding, and may help get beyond previous absolute assumptions that cause conflict (as in the first and third examples above), but this is still undermined by the new interpretation itself being absolutised. The third example (about UK productivity) and the final one (about the Middle Way) are somewhere in between: they offer interpretations that may be relevant and helpful in some circumstances, but may become limiting and unhelpful in others.

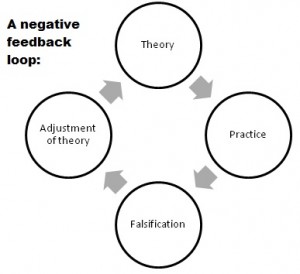

As an alternative, I want to suggest that we not only need to recognise the limitations of our interpretations, but also take responsibility for them. When we assume that our interpretation is the only possible one, we tend to see it as inevitable that we should think in this way: either because it allows us to make claims that are ‘true’ or ‘false’, or because we assume that ‘nature’ dictates how we should think. However, as long as we experience alternatives, we can also experience choice in our interpretations. If you choose to always interpret a particular politician’s statements in the worst possible light because it fits your ideological commitments to do so, then you are increasingly responsible for such a choice the more alternatives you become aware of. If you choose to only interpret the Middle Way in traditional Buddhist terms, you are responsible for deciding to do that to the extent that you have encountered alternatives. You cannot simply avoid that responsibility by appealing to Buddhist tradition as possessing the ‘true’ interpretation.

In my experience people often find it easier to recognise this point in relation to another person than in relation to ourselves. We commonly experience problematic misinterpretation of others and then have to painfully clear it up in order to maintain our relationships with them: that’s the normal grist of social life. Recognising that there was not something that we ourselves ‘really meant’ is much harder, though. We can be taken by surprise by someone else’s reaction because the interpretation they made was not the one at the forefront of our minds, but that doesn’t prove that it wasn’t in the background somewhere. So often “I didn’t really mean it” is a shortcut for “My dominant feelings are friendly, even though there’s always some ambiguity in these things.” The value in giving expression to those ambiguities in humour is, on the contrary, that there isn’t something we ‘really meant’ – rather a set of meanings within us that we can play with.

When it comes to texts and words, feelings can run even higher. For some reason, when it’s written down, it becomes far harder to recognise that the meaning we get from a text lies in us rather than in those apparently permanent words. That’s particularly the case with religious texts, which are deeply ambiguous. Yet relating positively to religious texts as sources of inspiration seems to me to depend very much on acknowledging our responsibility for interpretation, and that interpretation is part of the practical path of our lives rather than a prior condition for it. For example, interpreting the sayings and attitudes of Jesus in the gospels in terms that can be helpful rather than absolutizing is for me a way of engaging with Christianity positively. If, though, on the contrary, I assumed that a certain interpretation was a prior condition of my living my life helpfully, I would be obliged to fix that interpretation from the beginning and thus – however much the traditional view of the text may seem in theory to be supporting responsibility – I would be undermining my responsibility for my life.

But if the interpretation of religious scriptures causes debate, it is as nothing to the outrage that I find can be generated when one attempts to expand the meaning of a word or a term and deliberately use it in non-standard ways. For many, the dictionary appears to be a much more sacred text than any other. But the right to stipulate – that is, to decide for oneself on the meaning of a word one is using – seems to me to be at the heart of human freedom. Other kinds of freedom may turn out not to make a lot of difference, if the way we think about how to use our freedom is constantly limited by conformity to the tram-tracks of accustomed ways of using words. More than anything, I think it is the dualisms or false dilemmas implicit in the ways philosophers and other habitually use certain abstract words that requires challenging: self and other, mind and body, theism and atheism, freewill and determinism, objective and subjective. To use words in new ways, whilst trying to make one’s usage as clear as possible, seems to me the only way to break such chains. Stipulation is never arbitrary, but always builds on or stretches existing usage in some way. It does not threaten meaning, even if at times it can cause misunderstanding, but on the contrary in the long-term aims to make our terms more meaningful by keeping them adequate to our experience.