Though I’m now trying to give up the common practice of using ‘myth’ to mean falsity, I must also confess to having long used the term ‘hagiography’ (which means the written life of a saint) pejoratively, to mean a one-sided adulatory biography. Both these usages, though, tend to reduce meaningful symbolic material to claims about facts, when their chief significance doesn’t consist in anything of that kind.

Recently I’ve been rethinking my assumptions about hagiography when reading the Life of St. Cuthbert by the Venerable Bede. Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon saint from Northumbria in north east England, closely associated with the holy island of Lindisfarne, and Bede is the scholarly monastic writer of the early eighth century, better known for his ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicles’, though he wrote in Insular Latin (the weird form of Latin we used to use on these benighted islands). In his youth, though, Bede knew and served Cuthbert. Though he claims to have composed it only on the basis of reliable testimony, Bede’s life of Cuthbert is just one damned miracle after another. He cures the sick all over the place. An eagle brings him food in the wilderness. His incorruptible corpse cures the sick too. And when ravens steal straw from the roof of his island hermitage, he banishes them until they come back and apologise, with “feathers outspread and wings bowed low”. What are we to make of all this?

For me this is another opportunity to apply the thinking I’ve been developing in my book The Christian Middle Way (which I’ve drafted and am now hawking around publishers), where I thought about the interpretation of Jesus’ miracles in the New Testament. As regards factual claims about miracles, I’ve long accepted Hume’s argument that accounts of miracles are more likely to be mistaken than otherwise, given that our other experience shows them to be extremely unlikely. Though the probabilities are against the correctness of miracles literally interpreted, we really don’t know. We can speculate about what ‘really happened’ and construct alternative explanations, but this is all likely to be a distraction from appreciation of the meaning of the stories about what happened. That meaning does not depend in any way on what ‘really happened’, but is rather a product of the ways in which the stories reflect the archetypal functions of individuals in the context of a particular culture’s interpretation of those archetypes.

St. Cuthbert’s miracles can be more deeply appreciated if one lets go of the factual questions and focuses only on these archetypes. To illustrate this, let’s start with the healing miracles. Here’s a fairly typical example:

One day, as he was going round the diocese giving saving counsel in all the houses and hamlets of the countryside, and laying his hand on the newly baptised so that the grace of the Holy Spirit might come down upon them, he came to the house of a member of the royal bodyguard whose wife lay ill and seemed to be dying. The man ran to meet him, knelt down and thanked God that he had come, brought him into the house, and made him most welcome…. Then the man told him that his wife was desperately ill and begged him to bless some holy water to sprinkle on her.

‘I am sure,’ he said, ‘God will grant her a speedy recovery, or if she must die, put an end to her long agony and take her without delay.’

Cuthbert had water brought, blessed it, and gave it to a priest to sprinkle over the sick woman. The priest entered her bedroom and found her lying there looking like a corpse. He sprinkled the bed, sprinkled her, opened her mouth, and poured a little of the life-giving draught down her throat. The patient was quite unaware of what was being done, but as soon as the water touched her an astonishing thing happened: she was immediately restored to full health both of body and mind. She came to, blessed and thanked the Lord for deigning to send such guests to cure her, and then, rising from her bed, ministered to those who had just ministered to her, the patient tending the physicians. (ch.29)

Let’s first note the context in which the healing took place. Cuthbert is laying hands on people to give them the grace of the Holy Spirit. The ‘Holy Spirit’ has become such a stock phrase in Christianity that it might seem almost meaningless, a dead concept, but the live meaning of it in experience is probably more about people recognising new possibilities and extending their awareness in ways that also lift up and broaden their emotions, symbolically related to the confidence expressed in the baptism ceremony. Cuthbert is making people aware of the possibility of new integration.

Note then also that when Cuthbert comes to the dying woman, he does not claim to have power over her illness. It is God who kills or cures, not him. ‘God’ here is also a way of talking about the conditions and reconciling people to them. If the woman had died we would presumably not have heard about this miracle, so the story of her recovery may just reflect confirmation bias, coincidence, selective interpretation and the placebo effect: but in the context, Cuthbert focuses our attention on acceptance of the outcome, helping people to adapt to the conditions, whatever they turn out to be.

In that context, like any other healer, he also demonstrates compassion. This compassion is inevitably selective, because he is human and cannot heal everyone. The story thus does not tell us about God’s justice, but rather helps to reconcile us to his selectiveness. Some will live and others die, and the causes of them doing so are very complex and beyond full human understanding. Yet at the same time an intervention that offers renewed confidence for the suffering person may produce a breakthrough, which can then be recorded and inspire others to similar confidence and openness to integration.

Finally, there is also the actions of the woman after her miraculous recovery. Again, this should probably not be taken literally, as in that case it might seem both medically questionable (she would need time to recuperate) and patriarchal (her service to men couldn’t even be interrupted by near-death!). What I find striking about it is the way it deliberately challenges our expectations. Who is sick and who is well? We attach these labels to people, but the conditions are often more complex. Those who have been ill often remark on this problem: that others don’t know quite how to treat them and are unsure about what they can or cannot be reasonably asked to do. They are shoved either into the indulgent category of convalescent or the negative one of malingerer, because we have trouble with coming to terms with the incrementality of health and have to turn it into black and white terms. Miraculous healing makes all things possible, and its function is to make us aware and appreciative of what is possible, and the ways we might be otherwise constrained by our expectations.

Just as in the life of Jesus, so in Cuthbert there are both ‘healing miracles’ and ‘nature miracles’ in which the saint is depicted as being able to participate in God’s control over nature. The following story can illustrate this other type of miracle, and again it is important to quote some of the context.

Not only the inhabitants of the air and ocean but the sea itself… showed respect for the venerable old man. No wonder: it is hardly strange that the rest of creation should obey the wishes and commands of a man who has dedicated himself with complete sincerity to the Lord’s service. We, on the other hand, often lose that dominion over creation which is ours by right through neglecting to serve its Creator. The very sea, I say, was quick to lend him aid when he needed it.

He set about constructing within the walls of his dwelling a small shed which should be big enough for his day to day requirements. It was to be built towards the sea with the floor over a long deep cleft hollowed out by the constant action of the waves. It was to be twelve feet long, for that was the length of the cleft, so he asked the monks to bring him some planks of that length for floorboards the next time they came. They willingly agreed, received his blessing, went off home and forgot all about it. Back they came on the appointed day but without the wood. He gave them a very warm welcome, commending them to god with the usual prayer, then asked ‘Where is the wood?’ Then they remembered. They confessed they had forgotten and asked him to pardon their negligence. The kindly old man soothed their anxiety with a gentle word and bade them stay till next morning: ‘For I do not believe God will forget my wish’. They complied with his request. The following morning when they went out there was a piece of wood of the correct length thrown up by the tide right under the site of the shed. They marvelled at the sanctity of a man whom the very elements obeyed, and blushed with shame at their own slackness in needing to be reminded by inanimate nature what obedience is due to saints. (ch. 21)

‘Coincidence’, I think, as you probably do too. But we don’t know whether or not it should be rightly described in such a way. What the story records, however, is the meaning of these events for the participants. The monks interpreted the driftwood as a divine rebuke because they were ashamed of their negligence, so for them it served the purpose of symbolising their limited awareness and its consequences, regardless of whether or not the driftwood was the result of supernatural intervention. Cuthbert, however, did not offer such a rebuke but responded kindly, presumably in awareness that the monks’ integration (and thus their remembrance of others’ needs in future) would be better supported by such kindness.

Where Bede sees creation as serving the servant of God, we can see a person who is integrated enough to have fully adapted to his environment, recognising both what he can and cannot do in it. He can make use of one piece of driftwood, but since he asked for ‘planks’ he presumably still needs more than this for his building project. He accepts those conditions that he has no power over, but makes the most of those that he can affect. He is emotionally as well as cognitively adapted, not just resourceful but also flexible in his expectations. Read helpfully, then, this story is not about power over nature at all, but about the balanced acceptance of our lack of power. Our ‘dominion over nature’ is only ours by right when we serve its creator: meaning that we only get what we want by recognising the full extent of the contrary conditions. Today, the belief in ‘dominion over nature’ has been blamed by thinkers like Peter Singer for the attitudes that created anthropogenic climate change, but if that belief had been better tempered by awareness and respect for conditions we would have been much readier to accept our role and its effects at an earlier stage when we could do more to prevent it.

So, miracle stories, read carefully with an eye for their meaning in context, can offer us inspiration rather than falsehood. I am not suggesting that this is what they ‘really mean’: rather that we can usefully choose to interpret them in this way – the Middle Way that avoids the reductions of presumed truth or falsehood. Hagiography of a more traditional kind thus takes on a new meaning. However little I learnt about the faults and shadows of the historical Cuthbert from Bede’s biography, I at least found some inspiring reminders of the meaningful wisdom of the past. I don’t take that as a justification for writing such hagiographies today, because it is more important for us to develop balanced beliefs about more recent lives. But Cuthbert for me, and probably for you, is much more of an archetype than a historical figure. The Anglo-Saxon world offers a distance that makes such symbolic power possible.

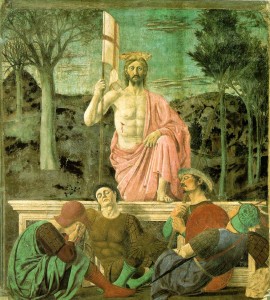

Picture: St Cuthbert Praying from Bede’s manuscript: British Library Yates Thompson MS 26. Reproduced for comment under fair use terms.

Quotations from Bede’s Life of Cuthbert come from ‘The Age of Bede’ trans J.F. Webb, pub. Penguin Classics. Reproduced for comment under fair use terms.

Links to some related posts:

Podcast discussion of faith

Franciscan Saintliness

Video: separating absolute belief from archetypal meaning

Audio talks on archetypes (scroll down)