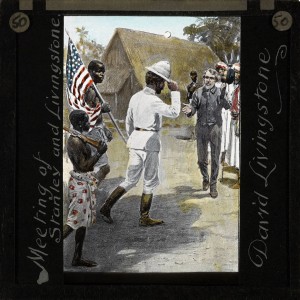

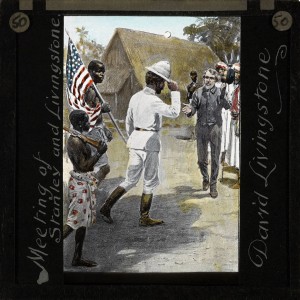

David Livingstone, Christian missionary and explorer of central Africa in the mid-nineteenth century, is quite an extraordinary, often contradictory, figure. Born in poverty and as a child working fourteen hour days in a factory in Blantyre, Scotland, he gained an education, became a qualified doctor and trained for mission out of sheer determination. As a missionary in what is now Botswana, though, after a while he went AWOL, quarrelling with his fellow missionaries and setting off on his own pioneering exploratory projects deeper into the unknown interior. He eventually became famous back in Britain as an explorer, and blazed the trail that later led to British intervention and colonisation in Malawi, Uganda, Kenya, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia. The most famous thing that many people remember about him was his meeting with Henry Morton Stanley at Ujiji, with Stanley’s legendary greeting ‘Dr LIvingstone, I presume?’: however, like many such famous sayings, this one probably never happened at the time, but was a later construction.

My interest in Livingstone has been developing since late last year, when, after the death of my father, I started reading the copy of Livingstone’s account of his earlier travels from my father’s bookshelves. I later followed this up by reading Livingstone’s biography by Tim Jeal. My father was also a missionary in Africa, as was my grandfather, and I have always struggled with feelings of ambivalence about their work – work that, though it changed a great deal during the course of the twentieth century, owed a great deal to Livingstone’s long-term influence. Were the Christian missionaries the agents of Africa’s ruin at the hands of colonial exploitation, or were they self-sacrificing heroes who helped to provide Africans with the basic tools of future development? Obviously both these extremes are misleading caricatures, but I wanted to find out enough to draw some kind of justifiable conclusion in between. Livingstone was not a typical missionary at all, but due to his subsequent influence he was a good place to start. How can one possibly apply the Middle Way in assessing the character, achievements and legacy of such a figure?

Well, to start with we could identify several extremes of presumption that depend on dogmas and are thus better avoided. One obvious one is the idealisation of Livingstone, projecting a hero archetype on him without awareness of the complex man behind the legend. The Livingstone Museum in Blantyre, Scotland, which I have visited, is rather guilty of this one-dimensional adulation. We can learn a great deal there about Livingstone’s phenomenal determination, endless endurance, tolerant kindness towards all Africans, stoicism in the face of endless tropical diseases and other hardships, and faith in what he believed to be God’s purpose for him. However, we won’t learn much there about the Shadow side: his monomania, arrogance, rash over-optimism, habit of quarrelling with others, stubbornness, and willingness to sacrifice others’ lives for his own ends. Much of the subsequent idealisation of Livingstone developed from the write-up he was given by Stanley, a journalist who thought him a new saint. Livingstone’s overwhelming sense of mission but serious lack of self-awareness is a kind of extreme representation of the strengths and weaknesses of Victorian Protestantism (some might even say of Christianity) in general.

But opposite to the absolutisation of Livingstone as an exemplar of a set of Christian values, there is an equally dogmatic dismissal of him, from those who see nothing good in what he was trying to do, and who fail to recognise the complexity of the values at work in that context. At the heart of this opposite response may lie moral relativism, implying that the values of pre-colonial African tribes must have been ‘right for them’ and thus that they were necessarily better off without interference. Accompanying this there might also be anti-colonial political beliefs, with perhaps (from Westerners such as myself) a dose of post-colonial guilt. But pre-colonial Africa was not a paradise, and it was not untouched by outsiders. There was much conflict between tribes including feudal dominance by some over others, routine enslavement of the losers in tribal wars, and well-established slave trading conducted both by the Portuguese and the Arabs. As to whether other common features of African society, such as polygamy, or victimisation due to witchcraft beliefs, would have been better left alone because the alternatives offered by Christian culture were necessarily worse for them – well, this strikes me as at least debatable, and hardly to be assumed without question. There is clearly a big danger of falling into the nirvana fallacy when assessing such things: just because colonial Christian culture had many weaknesses and injustices, we cannot assume that it was worse than the alternatives.

Other conditions that Livingstone’s contemporaries had to face up to were those of cultural inequality and colonial competition. Like it or not, the Africans were in an extremely vulnerable position relative to the West, due to their relative lack of technological, social and political development. If one nation, such as the British, did not adopt colonialist strategies, then not only might practices such as the slave trade persist, but other European nations might well jump in and inflict much worse. This happened, notoriously, in the ‘Congo Free State’ between 1885 and 1908, where Leopold of Belgium ruled a vast area of the Congo basin as a personal fiefdom and inflicted extreme forms of exploitation on the native population. The claim that ‘if we didn’t do it, others would’ can easily be used as an excuse for untrammelled capitalist exploitation, but the underlying point can also be correct. Though earlier on in his career Livingstone often seemed to feel that Africans were better off without interference from outside, later on he urged the British government to establish colonies as the basis for safer missionary activity. In arguing thus we could make a case that he was simply facing up to the conditions of the time.

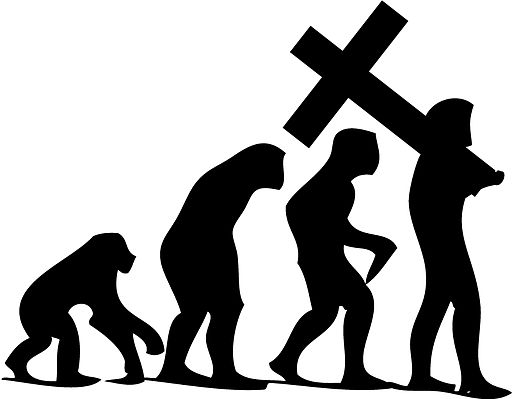

Another element that may make Livingstone’s legacy controversial for many today is the very idea of religious conversion. We may regard a missionary as someone whose job is to make converts to their religion: a process that might at the same time be highly disruptive to that person and their social context, and yet in other ways be superficial, involving the adoption of new absolute beliefs that may well be in conflict with the wider experience of the converted person. ‘Conversion’ in this sense is perhaps one of the worst features of religious absolutism and illustrates its fragility. However, his biographer wryly notes that despite Livingstone’s fame, he was by conventional standards a failure as a missionary, making only one African convert (the chief Sechele) who subsequently relapsed. However, in my view it is that very failure that forms the basis of Livingstone’s most admirable features. At quite an early stage Livingstone seems to have realised that trying to convert Africans to Christianity without an accompanying wider social and cultural change was both fruitless and unhelpful. Sechele himself illustrates this, as he tried to become a good Christian by giving up four of his five wives: of course this created widespread disruption and offence in his society. That also set up a conflict in Sechele which culminated in him committing ‘adultery’ with one of his former wives. Livingstone left Sechele’s township shortly afterwards.

Instead of converting people, Livingstone recognised that he would make a much more positive contribution to the lives of Africans by the more incremental use of cultural influence. Though he often spoke about Christianity (using magic lantern shows), this amounted to little more than spreading awareness, and he was also much concerned with providing medical aid when he could and with challenging the slave trade. One of his biggest obsessions was the belief that in order to give up the slave trade, Africans needed a positive alternative in the shape of legitimate trade that enabled them to access Western goods in exchange for other resources. To support legitimate trade, he sought out navigable rivers that would provide viable routes into the interior, and later urged the development of British colonisation that could provide protection and infrastructure as well as challenging slave-trading. Livingstone thus recognised the inter-relationship of different aspects of development, and thus the fruitlessness of pursuing narrow goals in isolation. That he was a ‘failure’ as a missionary was thus in many ways to Livingstone’s credit, and put him in harmony with some more recent liberal Christian attitudes to mission that are more concerned with development than direct persuasion.

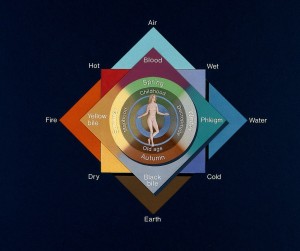

Livingstone also developed an interest in the scientific aspects of exploration, both in creating accurate maps and in recording the flora, fauna and geology of the region. Livingstone’s journals are full of lengthy asides in which he writes in some detail about some aspect of the country, such as the behaviour of red ants or hippopotami, or the varieties of fruit and the prospects for their cultivation. It seems clear that for him, ‘Creation’ was not merely an absolute or abstract idea, but also an experience of fascinated engagement with the world. Often he writes with similar appreciativeness about the customs of the people – to such an extent that it is jarring when one suddenly runs into a more typical Victorian complaint about, say, idol-worship, grotesque body art and ornamentation, or the unashamed nakedness of African ‘ladies’. Of course, Livingstone was a Victorian, but he also had remarkably wide interests and sympathies that he was able to apply in a totally new environment.

Livingstone’s temperament, however, was in many other ways antipathetic to the Middle Way. He was an obsessive, driven by successive schemes such as those of proving the rivers Zambezi and Shire navigable (both turned out to be blocked by major rapids) or finding the ‘Four Fountains of Herodotus’ as the source of the Nile. His final expedition, particularly, is a sad story of delusion drawing close to madness, as Livingstone gambled away his health and life on the false certainty of finding the source of the Nile further south than other explorers had placed it. Wandering around eastern Africa with very few of the necessary resources or followers, subject to lengthy bouts of fever that meant he often had to be carried, Livingstone became increasingly isolated from European peers who might have challenged his fixations. He was relieved only by his meeting with Stanley, who lionised him rather than puncturing his delusions. It was not so much his Christian beliefs as his geographical ones that were the source of absolutisation that was Livingstone’s undoing. But of course the two were also connected, because Livingstone evidently had unassailable views about himself and about the path set for him by God: a path that he came to increasingly see in geographical terms. It is these kinds of states that led him apparently not to care when his European followers were killed on the disastrous Zambezi Expedition, and to a coldness in which others seemingly became tools in his grand designs.

However, without this intense single-mindedness, Livingstone would never have been who he was. He would never have studied Latin after a fourteen hour day in the cotton mill, and thus not managed to escape his background. He would also probably have achieved far less as an explorer. Should we wish that those with intense left-hemisphere dominance did not have it, when it was so constitutive of who they were and what they did? I think not. Would Livingstone’s career have been more consistently successful if he had been able to introduce a more balanced perspective, albeit from his skewed starting point? Perhaps. But rather than indulge in counter-factual speculations that depend on hindsight, it’s probably better to recognise that we don’t know how far Livingstone’s less savoury qualities were inextricable from his more positive ones. Somewhere, there was probably a better balance that could have been struck, but only Livingstone himself could have found that point of balance without betraying the very things we admire about him.

So should we revere ‘great men’ like Livingstone, who did extraordinary things that were often at the expense of balanced judgement? Of course, I’m going to suggest that we should strike a balance, not revering them unconditionally, but also trying to appreciate positively what they did achieve. That balanced position is probably more powerful than mere hero-worship in the long run, because it relates to our wider experience rather than just our uncritical, abstract constructions of heroism. For the same reason, I think a biography that reveals the complexity of a historical figure is much more powerful than a hagiography that portrays a one-sided view of them. In the process of engaging with them in such a balanced way, we also simultaneously engage with aspects of ourselves, and by understanding Livingstone better, I feel I have got a little bit further in understanding the complex issues that lie behind the actions of my missionary ancestors.

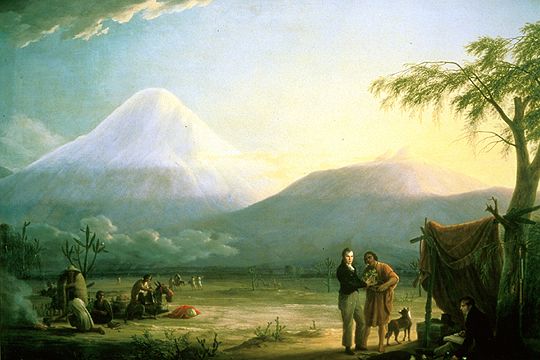

Humboldt’s way of doing science united analysis with synthesis in a way that seems to be largely lost today. His general conclusions could be backed up with detailed evidence from observation that was often first-hand, but at the same time he could pan out and make links between diverse fields of study. For example, he noted the effects of the Spanish colonial system on the environment of South America, and the impoverishment of plant and animal life it was already creating in some areas, even whilst abundant life thrived in those less affected by human interference. He also linked human-created deforestation to a feedback loop of climate change, as the lack of trees desiccated a local environment. To make links in this way, across the boundaries of politics, botany, meteorology and geography, is to synthesise, creating new understanding, rather than just to analyse causes and justifications within an accepted field of discourse.

Humboldt’s way of doing science united analysis with synthesis in a way that seems to be largely lost today. His general conclusions could be backed up with detailed evidence from observation that was often first-hand, but at the same time he could pan out and make links between diverse fields of study. For example, he noted the effects of the Spanish colonial system on the environment of South America, and the impoverishment of plant and animal life it was already creating in some areas, even whilst abundant life thrived in those less affected by human interference. He also linked human-created deforestation to a feedback loop of climate change, as the lack of trees desiccated a local environment. To make links in this way, across the boundaries of politics, botany, meteorology and geography, is to synthesise, creating new understanding, rather than just to analyse causes and justifications within an accepted field of discourse.