Carl Jung’s Red Book contains an extraordinary personal account of engagement with archetypal figures in a series of induced visions. Robert M. Ellis, who has a forthcoming book on the subject, explains how it can also be an inspiring resource for the Middle Way. This talk was given on Zoom on 19th April 2020, as part of the Virtual Festival of the Middle Way. It is followed by questions from the audience.

Category Archives: Great Thinkers

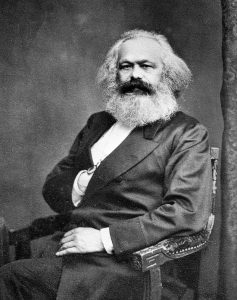

The New Class Struggle

In recent weeks I have been hacking my way through piles of exam papers, particularly featuring a question about Marx. Although this activity generally requires the suppression of all creative impulses in favour of total concentration, I still haven’t managed to stop myself engaging in some reflections about the relevance or otherwise of Marx’s beliefs about class struggle today, and how it all relates to the Middle Way. Now that I’ve finished the marking, I’m finally at sufficient liberty to write down my thoughts.

In ‘The Communist Manifesto’, Marx and Engels famously described the whole of human history as a history of class struggle. In one way or another, they say, the propertied classes have constantly found new ways of exploiting the unpropertied proletariat, in differing circumstances from ancient slavery to the factory floor. However, they go on, capitalism creates such extreme exploitation that eventually the workers “will have nothing to lose but their chains”. Purified by their total exploitation, they will overthrow the bourgeoisie in a revolution, which will usher in a merely temporary dictatorship of the proletariat, followed by the ultimate stability of the communist society.

The elements of dogma in this story are not too hard to identify. The socio-economic determinism is one: Marx’s ‘inevitable’ story shows no signs of turning out quite like that. The purification of the proletariat through suffering is also a projection that seems to have no basis in psychological, let alone historical, conditions. Far from gaining the ultimate wisdom to finally end social and political conflict, people who are suffering acutely tend to get more stressed and more reactive. It’s only if you are very well prepared for your suffering that you might be able to learn from it, but even then it’s unlikely to bring you to an absolute state of moral perfection.

Nevertheless, the power in Marx’s story, fuelling several revolutions, also suggests to me that there must be some insights in it, mixed in with the dogmas. The story that history is a matter of class struggle does seem potent, because it is indeed quite possible to analyse history in that way. More profoundly, though, class struggles are also struggles within individuals, who identify with different sets of beliefs that may either prioritise narrow economic interests or wider values. Those conflicting values also defy resolution because they are framed in absolute terms. When you feel that you have to choose between your job and your conscience, for instance, that is ‘class struggle’ in a the wider sense, whether you are a nineteenth century mill worker or a modern Conservative Member of Parliament. You can focus on class struggle sociologically and ignore the psychology (as Marx did), or you can focus on resolving the psychology of the personal struggle and ignore its political dimension (as in the recent phenomenon of ‘McMindfulness’), but the phenomena you are dealing will have all these dimensions, and the tendency to ignore some of them is an unfortunate result of over-specialisation.

Property can provide powerful vested interests, but vested interest is not the only human motivation, so I cannot agree with Marx’s assumption that the story of class conflict is only about the division between those who have property and those who do not. Instead, it seems to me more powerfully to be between those who absolutise narrow motives (including, but not limited to, property interests) and those who, whilst remaining human and having interests, are capable of thinking provisionally about them and weighing up different values. Ironically enough, those who are capable of doing this quite often have a modest amount of property, which has given them enough security to be able to start thinking provisionally. Those who have no property at all are often (but not always) so insecure that it’s difficult for them to avoid thinking in absolute ways that are constantly fuelled by craving and anxiety. No, the proletariat are not purified by their suffering. Rather their suffering makes them easier for unscrupulous absolutists to exploit.

So what is the class struggle today? Well, we are in the midst of it. The US and the UK particularly are currently wracked by political conflict that seems to have a strong class basis. That political conflict involves ongoing polarised disagreement about climate change, about nationalism, about social justice, about the rights of minorities, and about the role of the state, along with many other associated issues. It’s not a conflict between the property-owning bourgeoisie and the propertyless proletariat though. Rather it’s primarily a conflict between, on the one hand, a cabal of autocrats and billionaires with their numerous stooges, and on the other, middle class intellectuals. Not all members of any particular socio-economic group are necessarily on one side or the other – there are still middle class intellectual climate change denialists, working class internationalists, and billionaire liberals. Nevertheless, the conflicts have a strong class dimension as well as a psychological and philosophical dimension. It would be surprising if they didn’t, given how important social class is to our identity.

The ‘middle class intellectual’ class has not been merely created by material conditions and accompanying vested interests, as Marx would tell us. Rather, they have come to appreciate conditions better, and overcome some of their biases, by having their minds opened in one of a variety of possible ways. University education and professional training provide the most common vectors for it (as shown in Robert Kegan’s work on the contexts for what he calls stage 4 and 5 adult psychological development). Travel, friendship, study, art, and religious experience all provide other possible routes to bigger perspectives that may help to inoculate you against becoming a stooge.

The new propertied exploiters, on the other hand, are defined either by their narrow focus on power and economic advantage, or by other dominant absolute beliefs that facilitate that exploitation (such as religious fundamentalism). The majority of their supporters, though, are subject to what Marx called ‘false consciousness’: that is, they have been influenced into a set of beliefs that are against their own long-term best interests. The sources of false consciousness now come overwhelmingly from media manipulation that can apparently be traced back to autocrats and billionaires, from Fox News to the Daily Mail to Russian troll factories. This media bias chart provides a useful reference of the sources of such manipulation (which are found on left as well as right, but are overwhelmingly weighted towards the right). The strong links between climate change denial, the fossil fuel industry, and right wing politics are also confirmed by a number of academic studies.

In Marx’s analysis, intractable class conflict can come to an end only through violent revolution that breaks the mould of the system. Unfortunately this seems to be another of his delusions, if the evidence of actual revolutions is anything to go by. A revolution may change those in power, but it is unlikely to change the systemic patterns of interaction, which are likely to reassert themselves to a greater or lesser degree (as they did in the Soviet Union). The stakes in our new class conflict, though, are far higher than just the exploitation of one class. The very survival of human civilisation is at stake. The conflict may end in the ‘revolution’ of the destruction of all, or it may be gradually ameliorated through changes in the ways that we respond to conditions. Either way, though, the middle-class intellectuals will evidently prevail in the long-run, just as Marx predicted that the proletariat would prevail, either by being proved right or by running the world their way. That’s not because they’ve been purified or because their perspective is perfect, but rather because they imperfectly recognise that their perspective is imperfect when their opponents do not.

Is this another story as incredible as Marx’s? I think it identifies some of Marx’s insights (class conflict, its intractability, its relationship to ideology, its asymmetry, and the nature of false consciousness) whilst also drawing attention to his dogmas (determinism, absolutisation of vested interest, purification of suffering) and limitations (ignorance of psychology, ignorance of ecology). Marx was concerned, most basically, with how people address conditions, but the ‘science’ with which he interpreted this was heavily loaded with false assumptions. The updated story I’m offering in its place may also be based on some false assumptions, but at least it is based to some degree of recognition of the need to address such assumptions (Marx tended, instead, to say that his story was ‘science’ and everyone else’s was ‘ideology’).

I expect some of the first reactions to that alternative story to be based on false equivalence, which is a common absolutist strategy (think of Trump drawing equivalences between white supremacist demonstrators and their opponents). For an absolutist, everything is dual, and there can be no such thing as better judgement through provisionality. Their opponents are therefore always assumed to be as absolute as they are, and they will insist on reducing all complexity to that equivalence. Incremental marks of credibility (such as expertise, relative lack of vested interest, ability to observe, and corroboration) as well as every kind of evidence and every widely-used value, are ground down by absolutists into the same false equivalence. However, as Marx recognised, the class struggle is asymmetrical. One side is right and the other wrong (even if it’s not always clear who is on each side), because the wrong side is entirely blinded by its assumptions, totally immersed in confirmation bias. We are all subject to confirmation bias, but some of us are facing up to this fact and others are not.

The other objection I am expecting will be to point out a false dichotomy. “It’s not as simple as that,” you may say. “Surely there were not just two conflicting classes in Marx’s day, and there aren’t now either?” I agree. I am only trying to make sense of the idea of “class conflict” by separating out the elements that seem to demonstrably cause conflict from those that are just Marxian dogmas. However, any generalisations we make about “classes”, especially when they involve determinately dividing people up, are fraught with all kinds of complex difficulties. That’s why I only want to define the “classes” in terms of their relationships to absolutisation. Whenever you or I are dominated by absolutisation, we’re in the repressive class, as exploiters or their stooges, even if we’re middle-class intellectuals. If we cease to do so and start to judge provisionally, even if we’re in the pay of Fox News, we cease at least temporarily to be in that exploitative class. We cannot define the classes sociologically in any way that I find remotely satisfactory. The social categories I have used above can only be proxies for psychological ones, and are just ways of pointing out that the psychological conditions do have constant social implications.

Psychologically, too, absolutism is not defined by counter-absolutism, but by its own assumptions. Once again, then, we also see that the Middle Way is not a compromise. If we respond to absolutists with counter-absolutism (as some left-wing absolutists do) we become absolutists. However, if we respond critically but with confident provisionality, we are not being dogmatic. The practice of the Middle Way is provisionality, not compromise, and the confidence with which it needs to be taken up must not be automatically mistaken for dogma. The Middle Way seems to be the only practical solution to the class conflict that so much concerned Marx.

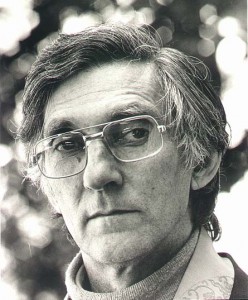

On the Death of Sangharakshita

Over much of the past year, I have been working on a book that is a critical evaluation of the thought of Sangharakshita, the founder of the Triratna Buddhist Movement (formerly the FWBO). This is an exercise in trying to apply the Middle Way to a set of approaches that greatly influenced me in the earlier part of my life, from the mid-1980’s through to 2008, when I resigned from the Triratna Buddhist Order. I have been trying to test Sangharakshita’s ideas by standards that I take to be entirely practical – the standards of Sangharakshita himself at his best. When I was involved in Triratna myself, I actually had little personal contact with Sangharakshita, but had a much closer relationship with members of the Triratna Order who referred to him constantly. Now that I have taken up an evaluative task from without, though, I have actually seen more of him – having six discussions with him between January and June this year. I had arranged a seventh this week, only to hear today that Sangharakshita, after being admitted to hospital with pneumonia, had died. Just as I was reaching the conclusion of my book, by coincidence, Sangharakshita’s life itself has concluded. This is a long-expected event about which Sangharakshita himself was very straightforward, but death still always takes us by surprise.

It is probably fair to say that, without Sangharakshita, there would be no Middle Way Society, at least in the form this one takes. It is from the movement that he founded and shaped that I experienced a living example of a spiritual movement that takes universal elements from Buddhism to apply them in the West, and that puts the emphasis on integrative practice rather than merely belief. It was this model that had influenced me most – both positively and negatively – when I proposed setting up the Middle Way Society, and especially that made me feel that retreats with a focus on practice as well as theory should be an important part of the society’s activity.

Sangharakshita did set considerable store by the Middle Way, and recognised it as an important aspect of Buddhism. One of my discussions with him (in May this year) was recorded as a podcast interview, and was on the theme of the Middle Way and its relationship with Buddhism. I have reproduced this podcast again here. The most interesting part of it begins at around 43:42, where I ask him whether the Middle Way was effectively part of his thinking as he ‘translated’ Buddhism to the West and set up the FWBO/Triratna. Sangharakshita says that he didn’t think it was very much, but also admits that perhaps it should have been, and agrees with me about the distinction between Buddhism and the Middle Way – both that the Middle Way can be found beyond Buddhism, and that Buddhist commitment doesn’t necessarily require people to pay much attention to the Middle Way. Instead, his emphasis was on commitment to the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) as constituting Buddhism.

During the past year, I have read far more of Sangharakshita’s work, and reflected on it far more, than I ever did in the days when I was formally (but often reluctantly) his disciple. This process has confirmed me in my view that this point about Sangharakshita’s attitude to the Middle Way is central to understanding both his strengths and his weaknesses. His strengths, at the heart of what he has achieved in Triratna, all arise from the engagement of aspects of Western culture with aspects of Buddhist teaching. His account of mind reactive and creative provides a universal and practical account of Buddhist conditionality teachings. His use of the idea of integration is highly compatible with psychological approaches, and his emphasis on individuality found fertile ground in a liberal democracy. His ideas about provisionality and experimentation even offered a nod towards scientific method – though one that unfortunately did not extend very much further than a nod. All of these offer different approaches to the kinds of judgements that we make when trying to practise the Middle Way – more creative, provisional, integrated and autonomous judgements – and were not necessarily tied to any commitment to the Buddhist tradition. His talk of archetypes even provided ways of interpreting Buddhas in a similarly helpful fashion. This was ‘universal dharma’.

However, to also understand Sangharakshita’s limitations, it is important to take into account his background. As a boy, he spent years in bed as an invalid with a supposed heart condition, reading avidly and setting up a lifetime’s habit of autodidacticism. This made him into a creative and original thinker, but never trained him in the academic habits of consistent critical thinking, nor of adapting his ideas in response to others’ criticism. He was thus poorly set up to actually practise provisionality, or to learn effectively from scientific approaches (which he tended to caricature as ‘materialism’). At the age of sixteen, he says that he read the Diamond Sutra and immediately realised that he was a Buddhist. This evidently gave him a strong intuitive commitment to the Buddhist Tradition that lasted for the rest of his life. Although he was willing to question aspects of Buddhist tradition, such as monasticism, when experience confronted him with its inadequacies, his commitment to the Buddhist tradition often also made him assume that it must be right and accord it endless benefit of the doubt. He allowed members of his Order to be (softly) “agnostic” about rebirth, for instance, but still expected the teachings on rebirth to yield ultimate truths, rather than being willing to drop belief in rebirth as a practically unhelpful aspect of the tradition.

I think these tendencies provide a basic explanation of why Sangharakshita often completely ignored the Middle Way, subjugating it to the authority of Buddhist tradition and making extremely one-sided pronouncements on all sorts of subjects, from the relative spiritual aptitude of women to the supposedly anti-individual nature of Christianity. It does not seem to have occurred to him that the critical process he began in relation to the Buddhist tradition required some sort of coherent justification beyond the limitations of that tradition itself. So instead, many of his followers have substituted the authority of Sangharakshita himself for any such coherent principle. He himself insisted, as recently as 2009, that the basis of the Order should just be what he chose it to be, apparently regardless of the basis on which he judged that it should be like that, and whether that basis stands up to scrutiny. In my view any such absolute appeal to authority as constituting the Triratna Order is completely incompatible with the Middle Way, and with the practical development of integration, provisionality, creativity and individuality that actually makes that Order as effective as it is. As long as it is followed, the Order will be subject to a deeply undermining form of cognitive dissonance, with the authority of Sangharakshita’s words at odds with the practical requirements of the conditions. It is also only because of this contradictory over-reliance on Sangharakshita’s own authority that his moral mistakes in sexual conduct turned out to be so upsetting for so many people.

Now that Sangharakshita has left us, there will understandably be an immediate response of grief and shock in Triratna. However, once things settle down, the Order will presumably feel the same release that children may feel at the death of a parent. They can now make the decisions for themselves to a much greater extent than they could before, and they can choose to make the basis of the Order whatever they choose to make it. I would urge them to make practical and universal principles the clear basis of the Order, with Buddhist tradition having an archetypal and symbolic rather than authoritative function. Only in that way can they extend the benefits of the best of Sangharakshita’s teaching, and of some of the excellent practices they have built up, to a wider section of the population. Heading the home page of Adhisthana, the retreat centre where Sangharakshita lived and where his funeral will shortly take place, is a quotation from Gustav Mahler: “Tradition is the handing on of the flame, and not the worship of ashes”. Now is the time when we will see if the placing of that quotation means what it says.

For myself, I may well go to the funeral to pay my respects to the man I got to know more personally during his final year of life. I also expect to finish drafting my book fairly soon. After that, I am looking forward to moving on from Triratna-related concerns to wider and more pressing ones – particularly those that relate to the political situation and climate change. I have no intention of getting deeply sucked into Triratna again in the long-term, much as I will have learned, and I hope also perhaps contributed, by a temporary period of re-engagement. If Triratna starts to take the Middle Way more seriously, I will welcome that with great gladness. If it does not, I’m happy to leave it to worship its own ashes.

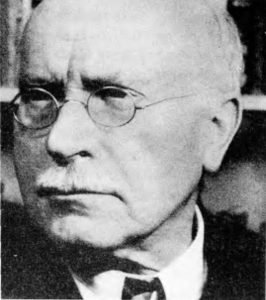

When we were very Jung

It was about 2 years ago now when I first read Jung’s Red Book, which had been published in 2009 after sitting unpublished for nearly a century. Although I previously had a long-standing interest in Jung, reading that extraordinary text brought me to a new level of engagement with Jungian ideas, in recognition of their potential strength of connection with the Middle Way. The first fruit of that engagement was a series of blogs (1,2,3 & 4), but then there were also new reflections on Christian symbols that contributed to The Christian Middle Way, the giving of a talk at the Bristol Jung Lectures, and also the writing of a book on the interpretation of the Red Book which I am currently trying to find a publisher for (The Jungian Middle Way). The other aspect of this engagement that I want to reflect on here, though, has been increasing engagement with Jungians. Who are the Jungians? How do they understand themselves? I’m not sure I can really answer that question, but can only give you some impressions. I’m not sure I’ve ever been quite so baffled by a group of people who in any way shelter under the same label.

There does seem to be a Jungian community – one that gathers in major cities across the Western world for talks or therapeutic training, but that also has a significant online presence. There are a number of Jungian groups on Facebook, and one of their distinguishing features is often how vast they are. The core of that community seems to consist in therapists, but there is obviously also a wider audience from a public that has been grabbed, as I was, by the Red Book, or by earlier popular Jungian writings such as ‘Man and his Symbols’ or the autobiographical ‘Memories, Dreams, Reflections’. Anyone with an imagination can be readily intrigued by Jung.

What I have found most baffling is the range of people and the range of their attitudes. This probably reflects the ambiguities in Jung himself. At his most clear and reflective, Jung is committed to writing only on the basis of experience, whether that takes the form of psychological evidence from patients or from his personal experience. He is unsurpassed, in my view, in his understanding of the meaning of that experience. At his best, he clearly separates archetypal meaning from projections of that meaning onto the world – so, for example, the Shadow is clearly an archetypal form representing our own hatred and rejection, which we should avoid projecting onto people or other entities, but rather symbolise in its own right as Satan or another evil figure (see my earlier blog on evil). In other places, however, Jung relaxes this distinction and drifts into metaphysical assertions (for example in the Gnostic Seven Sermons, near the end of the Red Book), or into groundless empirical assertions – famously including the dawn of the Age of Aquarius, and also including some very dodgy generalisations about gender, nationality and race.

Jungians, I’ve found, are similarly very varied. Some Jungians are balanced, sane, wise, thoughtful, pragmatic people whom I’ve been grateful and honoured to meet. Others are not so wise or discriminating. I am not going to mention any specific names, but here are some of the less balanced types I’ve encountered: the New Age intuitive who takes astrology seriously as a guide to the future; the spiritual intuitive who claims to just KNOW God; the obsessively rigorous scholar who won’t accept anything not clearly proved in the text of Jung’s writings; the pseudo-historian who has a detailed account of a past matriarchal civilisation that he believes could teach us all peace; and the self-appointed online authority who insists that I must be ‘overthinking’ and not using my feeling and intuition if I dare to criticise anything Jung said. Sometimes the Jungian community seems like the nearest we have to a substantial Middle Way community, but at other times it seems like a bunch of credulous hippies, and at other times a rather sinister cult.

It seems to me that perhaps the biggest issue creating this diversity, apart from the inconsistency of Jung’s own writings (and the tendency of some Jungians to absolutise them as a necessary source of truth), is the question of the status of intuition. Intuition is the means by which most of us are able to deal with complex experience readily. We ‘get the gist’ of a situation, or a perspective, or a person through a holistic overview that unconsciously draws on lots of previous experience of similar situations. Those of us who are more inclined to rely on our intuitions may thereby gain an advantage in understanding and preparedness, when compared to someone who tries to work everything out by laboriously matching concepts to what they sense. Intuition also gives us archetypal meaning by unconsciously formatting what we experience. So intuition is not flakey – it’s necessary and everyone uses it. Jung and Jungians, though, perhaps rely on it more than most as a source of insight into psychological forms and relationships.

The crucial issue is that of what intuition can justifiably tell us. On the one hand it can provide a ready access of meaning with which we can understand our experience. However, the problem with Jungianism at its flakiest is the way in which people feel they’re justified in deriving absolute facts directly from intuitions. The meaning gets translated directly into beliefs about the world without going through an intervening process of critical reflection. So that’s why we get people who believe in astrology, think they ‘just know’ God, or know the essential characteristics of, say, Germans, or women, through the operation of intuition. In the terms of Middle Way Philosophy, they are absolutising.

The research on intuition discussed by Daniel Kahneman also shows how unjustified this is. Kahneman compares studies done on the intuition of firefighters and stock traders. Experienced firefighters had excellent intuitions about when a burning building was about to collapse, because the conditions in burning buildings follow a predictable enough pattern to make unconsciously processed information reliable. However, stock traders performed worse than random when they followed their intuitions about which stocks would do best. In the past I’ve written a story about this contrast. The more complex the thing you have intuitions about, the less reliable they are, and the more important it is to slow down and actually think about it and consider the evidence.

Jungianism unfortunately has a bad reputation amongst many people who are scientifically or philosophically trained, because of this unjustifiable use of intuition to draw absolute conclusions. These hard STEM types are missing out on a good deal of very helpful material in Jungian thought. I would urge them to reconsider. But I also really wish that respect for empirical evidence was a more widespread and consistent feature of Jungian thinking than it is. You really don’t have to give up on the riches of Jungian meaning to expect adequate justification for your beliefs. You really can have your cake and eat it here. So perhaps we should all grow up.

Some other resources on Jung on this site:

Jung: Middle Way Thinkers Series

Podcast Interview with Helena Bassil-Morozow on Jungian Film Studies

Picture: Carl Jung by Charles-Henri Favrod (CCBYSA 3.0)

The Buddha’s Breakthrough

What was the Buddha’s breakthrough? He gained enlightenment, right? Well, actually I’ve no idea. Just as I stay agnostic about the existence of God or its denial, likewise with the Buddha’s enlightenment. But recently I’ve been looking again in some detail at the sources on the Buddha’s life in the Pali Canon, and been thus reaffirmed in my view that the Buddha’s breakthrough was not enlightenment (or awakening, or however else you want to translate it) at all. His breakthrough consisted in the recognition of a method.

Let’s consider almost any other case of a historical figure who discovered a new method and then successfully applied it. Do we consider their method to be their most significant achievement, or what they did with it? Let’s take Picasso: was it more significant that he developed cubism, or that he painted Guernica or Les Demoiselles d’Avignon? Or Gandhi: was it more significant that he developed techniques of non-violent direct action that inspired many others, or that he made such a big contribution to the struggle for Indian independence? The further away we are in time and place, the more we are likely to see the significance of the method as far more important than the achievement. Why should the Buddha be treated any differently from that?

However, I’d say the case is actually much stronger with the Buddha than it is with either Picasso or Gandhi, because the Buddha’s method is of such universal importance. The Middle Way, understood as a principle of non-absolute judgement, can be applied by anyone anywhere to make progress from whatever point they’ve reached. By identifying and avoiding absolutisations, whether negative or positive, we can avoid delusions and thus make tangible progress, right now, being aware that absolutisations are our own projections. But enlightenment? It’s clear from human experience that we can make progress with greed, hatred and delusion, but profoundly unclear whether we could ever hope to eliminate them altogether. The description of the state of enlightenment as given in the Pali Canon also depends on metaphysical beliefs in karma and rebirth, because the Buddha is depicted as becoming enlightened by breaking them. Most importantly, no other human state is completely discontinuous. We can make breakthroughs, but they are never completely discontinuous, nor final, and never result in perfect knowledge of any kind. Belief in the Buddha’s enlightenment as an absolute is in conflict with confidence in the Middle Way.

Looking at the Pali Canon account of the discovery of the Middle Way, though, makes it clear how powerfully symbolic that discovery can be, because it involves such a dramatic puncturing of delusion. The Buddha has gone forth from the Palace where he began, and gone forth again from the cults of two different spiritual teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta. In each case, the social context involved people insisting that they had the whole story, and the Buddha recognised that they did not. Then he began to practise asceticism, and he describes trying to stop himself breathing and then nearly starving himself. He’s obviously in a closed, rather obsessive loop whereby absolute beliefs are violently in conflict with his body. So what makes the difference? How does he get out of that state and discover the Middle Way instead?

“I considered: ‘I recall that when my father the Sakyan was occupied, while I was sitting in the cool shade of a rose-apple tree, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, I entered upon and abided in the first jhana, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion.’” (MN 36:20)

He gets back in touch with a memory from his earlier life in the Palace, showing that the Palace was not all bad. This memory is an experience of jhana – of an absorbed meditative state that, crucially, could only have been developed through deep acceptance and relaxation of his body. He has moved decisively from grasping after absolute, disembodied ideals that only produce conflict, to an embodied point of view. From that will follow that he must develop in ways that are possible and realistic for people with bodies, rather than sharing the delusions of those who forget that they have bodies. Not only is his need for nourishment, and the body-awareness that forms the basis of meditative practice, part of that recognition of this embodiment, but also the Middle Way itself, with its sceptical and agnostic awareness that we cannot have perfect knowledge, but instead need to work incrementally and provisionally to integrate the energies, meanings and beliefs of our interrelated mind-body.

When he gives his first address to others following his enlightenment, the Middle Way is the first teaching he then gives:

Bhikkhus, these two extremes should not be followed by one who has gone forth into homelessness. What two? The pursuit of sensual happiness in sensual pleasures, which is low, vulgar, the way of worldlings, ignoble, unbeneficial; and the pursuit of self-mortification, which is painful, ignoble, unbeneficial. Without veering towards either of these extremes, the Tathagata [Buddha] has awakened to the middle way, which gives rise to vision, which gives rise to knowledge, which leads to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbana. (SN 56.11.421)

The version of the Middle Way that he gives here is one applicable to his audience: that is, the five ascetics, his previous comrades, who need to recognise that asceticism is not a helpful path. But it is already clear from the Buddha’s story that the path he has discovered is one that involves the capacity to question any claimed absolute, whether that consists of a belief about oneself, about ideology, about salvation, or any other matter. To show how much the Buddha uses this wider Middle Way, in his conduct, in much of his teaching, and particularly some of his similes, is a longer discussion, but it will form part of the book I am currently writing about the Buddha’s Middle Way.

It will no doubt be pointed out that whenever the Buddha refers to the Middle Way, he also describes it as the way to Nibbana (enlightenment), as he does in the quotation above. There is a positive way we can interpret this without accepting absolute beliefs about Nibbana, which is to see Nibbana as meaning the notional end-point of the Middle Way, pand thus effectively standing, archetypally and symbolically, for the Middle Way itself and the more integrated states that it can help us to develop. Just as God can be interpreted as a glimpse of our potential integration, so can enlightenment – as long as we separate these archetypal relationships clearly from beliefs about the existence of these entities, or indeed of any absolute (revelatory) information that is supposed to come from them. So, we can easily continue to be inspired by the figure of the Buddha, even if in some ways the term engrains an unhelpful emphasis on absolutes into the Buddhist tradition. The Buddha represents the potential integration of our psyches.

Though the Buddha ‘discovered’ the Middle Way in the sense of being the first person, as far as we know, to talk explicitly about it, he did not of course create it, any more that Newton’s ability to label ‘gravity’ and explain how it works magicked gravity into being. The ways in which it can be (and has been) discovered by others with varying degrees of explicitness needs just as much emphasis as the Buddha’s discovery. Nevertheless, that discovery itself, it seems to me, deserves a lot more celebration. The first thing the Buddha ate after discovering the Middle Way was rice porridge: why not eat that ceremonially in remembrance of the Middle Way (a sort of Buddhist eucharist)? His vital recollection of his experience under a rose-apple tree makes that tree perhaps just as important in our associations as the better-known bodhi tree. Here is an example. Eat a rose apple and think of the Middle Way.

Nevertheless, that discovery itself, it seems to me, deserves a lot more celebration. The first thing the Buddha ate after discovering the Middle Way was rice porridge: why not eat that ceremonially in remembrance of the Middle Way (a sort of Buddhist eucharist)? His vital recollection of his experience under a rose-apple tree makes that tree perhaps just as important in our associations as the better-known bodhi tree. Here is an example. Eat a rose apple and think of the Middle Way.

Pictures: (1) Buddha by Odilon Redon, (2) Rose Apple tree (Syzygium jambos) photographed by Forest and Kim Starr, CCSA 3.0