Our guest today is Dan Nixon. He’s a writer and researcher specialising in themes around attention, environmental philosophy and digital culture. A particular area of interest and expertise is the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty and he’s also a mindfulness teacher. He’s written a couple of essays for Aeon and his ideas have been picked up and discussed in the Sunday Times, The Economist and the Guardian among others. He co-lead Perspectiva’s work on the Digital Ego. He’s going to talk to us today about cultivating a spirit of questioning in relation to our digital lives.

Category Archives: Culture

Why the left fails – and how it can succeed

The UK is still reeling from the election results of a few days ago, in which Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party not only won a majority, but did so by capturing many traditional working-class seats across the north and midlands of England. Australia has experienced a similar election recently, whilst the US got there first with the surprise election of Trump in 2016. The devastating surprise in all of these elections seems to lie in how far working class people are prepared to vote against what seem clearly their own interests: namely, against improvements in the public spending they rely upon, and in favour of grossly inconsistent right wing governments, supported by big business interests who evade tax and impose exploitative working conditions on them. That’s even before we get onto the pressing issue of climate change, where all our interests are deeply threatened, and the right wing responses are generally either denialist or inadequately weak. The jokes about turkeys voting for Christmas have abounded.

But beyond that, how can we helpfully understand and learn from the underlying problem here? Very few analyses seem to drill down to the most basic issue, which is one of human judgement. Applying the Middle Way, one tries to avoid absolute assumptions, whether negative or positive – which in this case probably means avoiding the single cause fallacy. Why, then, do so many working class people – whether in Workington, Brisbane or Des Moines – persist in voting like turkeys? It’s very easy to take one kind of explanation and absolutise it, in accordance with the particular political concerns your experience has equipped you with, but in the process avoid the most basic underlying issues. We can blame leaders, we can blame biased and sometimes false media coverage, we can blame party policies and manifestos, we can blame party tactics, or even voter stupidity. All of these factors are no doubt part of the picture, but they need to take their place in relation to the question of human judgement. What actually decides the values that actuate people when they cast their vote?

In understanding this, I’ve found the following video from Rebel Wisdom helpful. It mentions a couple of things that I think are very relevant. One of these is the analysis of six foundational political values by Jonathan Haidt (authority, loyalty, sanctity, care, justice, freedom) – see my review of his book. Another is an idea that comes from Ken Wilber – the pre/trans fallacy: namely that people often react against a later stage of integrative development that has incorporated the more helpful elements of an earlier one, because they mistake it for the earlier stage. I do recommend watching the video if you have time, although it’s 35 minutes long. It doesn’t answer all the questions that I think need to be asked (which I continue with below), but it provides a very good starting point.

Where this video leaves us is with the idea of “performative contradiction”, namely the idea that the left contradicts itself unconsciously by committedly extolling the values of care and justice, but doing so in a way that feels exclusive to working-class people. Whilst I think that’s a good point, I also think it’s not sufficient to leave it there, because it has the implication that the left is to blame for being too exclusive by being intellectual, middle class etc, when these are largely just part of the conditions that middle class left wingers are working with.

However, if we take the six foundational values of Haidt and probe them further, we can start to ask what the values of working class people may be, and why they are opposed to those of middle class left wingers. The obvious answer seems to lie in those values identified by Haidt as more collective ones: authority, loyalty and sanctity. Haidt’s major point is that conservatives combine these three values with the others (care, justice and freedom), but ‘liberals’ (in the American sense) concentrate only on care, justice and freedom and fail to understand why anyone values authority, loyalty or sanctity. This is also somewhat hypocritical of the left, of course, because left wingers, being human, do have their own values of authority, loyalty and sanctity, but they tend to confine them to private life (family, friendships, religion, maybe business or professional relationships). Left wingers just don’t feel it’s appropriate to make political judgements on the basis of authority, loyalty or sanctity, meaning that they are more likely to be anti-elite, internationalist and anti-religious.

But do the working classes share these ‘left wing’ or ‘liberal’ types of value? It seems obvious to me that the majority do not, and the psychological preferences of the majority help to create cultural trends that subsume many more (such as the popularity of Brexit). Why, then, have working class voters in industrial towns across northern England traditionally voted Labour? Obviously care, justice and freedom are of some concern to these voters, but they are not prepared to use them as a sole basis of judgement without a good helping of authority, loyalty and sanctity to help them along. In traditional industrial northern England (where I spent much of my childhood) these sources of authority, loyalty and sanctity were clearly present in working class culture. Socialist leaders, some of working class origins, provided authority. Working class solidarity itself, particularly exercised through the unions, the pubs and the churches, provided the basis of loyalty. In the past, voting Tory would have been an unthinkably disloyal thing to do. Sanctity, too, was present in the power particularly of non-conformist Christianity in the earlier Labour movement. Even in the 1970’s, when I was growing up amongst the small towns south east of Manchester, the churches of each town would all parade with their banners and assemble outside the town hall, dressed up in pride for the ‘Whit Walks’ every Whitsuntide Sunday: a display uniting the sanctity and solidarity of the churches, the town and civic society (see this link for pictures: one of which is here).  However, under the impact of social and economic change, these sources of value are largely gone: church attendance has plummeted, pubs have closed, and unions have been seriously weakened. The left has become an increasingly middle class phenomenon, including those who may have been born into the working class but adopted middle class culture and expectations. The working classes are left to rudderless individualism.

However, under the impact of social and economic change, these sources of value are largely gone: church attendance has plummeted, pubs have closed, and unions have been seriously weakened. The left has become an increasingly middle class phenomenon, including those who may have been born into the working class but adopted middle class culture and expectations. The working classes are left to rudderless individualism.

I think there’s a further theoretical perspective that can shed light on this: that’s the work of Robert Kegan on the stages of adult psychological development. Kegan extended the work previously done by Piaget on how children develop, in the process identifying some quite well-definable stages in both the cognitive development and the changing values of adults. The video below gives an introduction to the five stages of development in Kegan’s thought.

The vast majority of adults are at either what Kegan would call the ‘interpersonal’ stage (stage 3), or at the ‘institutional’ stage (stage 4). In the interpersonal stage, we rely to a greater extent on other people’s approval as the basis of our values, so we could expect this to largely correspond to the ‘conservative’ six values thinking in Haidt’s analysis. If your relationship with others is the prime basis of your values, then authority and loyalty will continue to be important to your judgement. Care, justice and freedom will also be part of the mix, but not by themselves in too much abstraction from the social context to which you feel your loyalty. It is only when people are able to move on to stage 4 that they are likely to be able to adopt those ‘liberal’ values: justice, care and freedom applied systematically beyond the bounds of immediate group loyalties. If they are able to move beyond stage 4 into the ‘interindividual’ stage 5, they will then see the limitations even of these systemically applied values and how their interpretation is limited by contextual assumptions – but only a relatively small number of people manage this. Mistaking stage 5 for regression to stage 3 is the pre/trans fallacy mentioned above.

The crucial factor in people’s lives that helps them to shift from stage 3 to stage 4, according to Kegan, is likely to be either university study or the demands of a profession. To do either of these, generally speaking, you are forced to adopt more systematic habits of mind, and to adopt a standpoint beyond that of loyalty to your background group or social class. However, when you get a university degree or join a profession you almost by definition become middle class, and in the process are likely to adjust your peer groups, your housing, your location, and your voting habits. I can’t find any research that has been done on the correlation between Kegan’s stages and social class, but I would be astonished if there does not turn out to be a strong correlation when such research is done.

So, to return to the main theme, why does the left fail? Why do the working classes fail to support it? My hypothesis for the key answer is that they fail to support it because they are still at stage 3, and thus because they still require authority, loyalty and perhaps sanctity as an element in the basic values of what they will support. The reason is thus not primarily leadership, policies, media or tactics, although these all undoubtedly interact with people’s basic values and produce smaller short term changes in voting habits. With the growing individualism in society, the working classes have lost whatever basis of loyalty to the left they ever had. Instead, the conditions that produce systematic thought about the application of care, justice and freedom (along with systematic thought about how to respond to issues like climate change) are overwhelmingly those of university education.

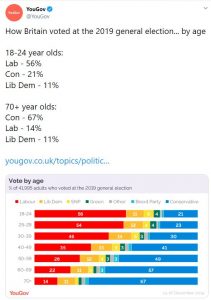

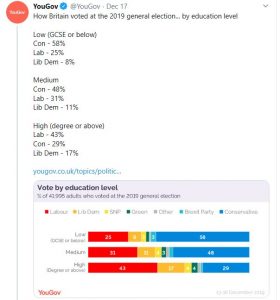

The voting figures for the recent UK general election show big disparities, not just by region, but by age and education. According to YouGov, age and education are now clearly the most important indicators of voting intention. The following graphs show just how big that disparity is.

But it needs to be remembered that these are not just social categories – they are also psychological ones determining how people make judgements.

But it needs to be remembered that these are not just social categories – they are also psychological ones determining how people make judgements.

So, how can the left succeed? Not by wooing the working classes back, but by coming to terms with the fact that the basis of left wing support is education – and that this means that in the longer-term, conditions are on their side. All they have to do is maintain the support of a majority of educated voters, and wait for higher levels of education to filter through the population. Of course, anything they can do to support and spread education is also part of the key to success. Reforming education itself so that it is more effective – including basic knowledge of the political system and more effective teaching of critical thinking skills for all – would also help.

The removal of unnecessary divisions on the left would also help a great deal to get them into power sooner rather than later. In the UK Labour and the Liberal Democrats are competing with each other and splitting the anti-Conservative vote in many seats, with the first past the post system making this disastrous in its effects. These parties need to merge or ally themselves in order to stand a chance, because they are largely fishing in the same pool of educated voters. the only differences between them lie in the degree of emphasis between the three ‘liberal’ values, with Labour emphasising care and justice rather more, and the Lib Dems trying to strike a balance between justice/ care on the one hand a freedom on the other. Their commonalities are much more important than their differences. Both parties now face a change of leadership, and it is to be hoped that the new leaders see the sense of creating an alliance rather than competing. In the Labour party, though, this means facing down those who are attached to the Marxist belief that social change must be instigated by the oppressed themselves: Haidt and Kegan between them have shown that this is wrong.

In my personal judgement, in the embodied situation I find myself in politically, a Middle Way judgement means that one needs to support the left. However, I can well understand that people will reach different political judgements by sincerely applying the Middle Way in different circumstances. I support the left, not because of any absolute commitment to care, justice or freedom (I think these need to be balanced with the other values, making me in some ways a small-c conservative – see blog on this), but because I think justice, particularly, has been neglected in the Western world since the rise of neo-liberalism in the 1980’s, and because systematic thinking is overwhelmingly needed to address climate change. My political views are pragmatically led. This is not the time for exaggerated suspicions of the state, nor for any other distraction from the big picture of the conditions we need to address and the best way of getting there. Nor is it time to give up hope. Tony Blair had many weaknesses with his strengths as a leader, but he seemed to be right in one well-known statement of his priorities: “Education, education, education”.

The MWS Podcast 148: Sally Kohn on the Opposite of Hate

Our guest today is Sally Kohn, who is arguably one of the leading progressive voices in America. A frequent guest on CNN, MSNBC and Fox News. Sally is a popular keynote speaker including most recently with the Forgiveness Project , talking about political division, hate, otherizing, diversity and identity — and how we can solve the deep problems of our past and present. Her first book ‘The Opposite of Hate’ came out last year and will be the topic of our discussion today.

MWS Podcast 148: Sally Kohn as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_148_Sally_Kohn

Stream podcast from Itunes Library

In Defence of, the Much Maligned, Twitter

“For any women who are compelled, against their wishes, to wear a Hijab, I would fully support such a notion [to arrange a #TakeOffYourHijab day in solidarity with the Iran protests]. Similarly, I would not like to see any woman compelled, against her wishes, to remove her Hijab either”.

I tweeted this on 31st December last year, in response to the suggestion by – counter-extremist, author, broadcaster and Founding Chairman of Quilliam – Maajid Nawaz that, what he calls the ‘regressive left’ would not support a Take Off Your Hijab Day, even though they have been vocal in their support of World Hijab Day. It’s an uncontroversial response in what I think was an interesting and important debate (one that had been inspired by the Iranian protests which were ongoing at the time). However, it’s not the content of this debate that I want to discuss here but what happened next and how it caused me to reflect  on my overall experience of Twitter (and online communication in general).

on my overall experience of Twitter (and online communication in general).

I’ve had loads of debates and disagreements on Twitter. These have covered a whole range of subjects and have involved people from a wide range of political backgrounds. I’ve debated with left-wing Jeremy Corbyn supporters about media bias and Donald Trump supporters about gun control, but the issue of Muslim women wearing head coverings, and the comments that I made about it, seemed to inspire a level of hostility that I hadn’t encountered on Twitter before. Now, I should say right away that, although it felt abusive at times, what I experienced was still extremely mild compared to what others – notably women – can, and do, experience on a disturbingly regular basis. Nevertheless, it was still quite shocking and, while I’m not one who takes offence very easily, it became pretty overwhelming. This was partly because of the frequency with which the criticisms came, but it was more to do with the nature of the onslaught. My points were largely being ignored in favour of increasingly personal attacks. Eventually, feeling deflated and tired following twenty-four hours of Twitter exchanges, I muted the conversation (meaning I could only view my own previous posts, but would not see anything else) and reported some of the most abusive participants, thereby bringing my role in the discussion to an end.

This spiral into uncivilised discourse all seems rather predictable. It’s a common trope to point out the negative and harmful effects of Twitter, and other forms of social media; it is often discussed by the public and widely reported upon by the media. I don’t want to play down this aspect of social media; it is real, it can have extremely severe consequences and there has not yet, in my opinion, been anyway near enough done to address it – by either the companies involved, various governments, or society in general. Online bullying, shaming, threats of rape, and the spread of destructive ideologies are just a few examples of a problem for which endless discussion has led to little in the way of meaningful action. Nonetheless, my experience, as described above, affected me in a way that was as intense and vivid as it was surprising. My initial weariness passed quite quickly, and what I was left with was the realisation that the overwhelming majority of my experiences on Twitter have  been positive. Sometimes deeply so.

been positive. Sometimes deeply so.

Sure, as I said before, I’ve had lots of debates and arguments that have often felt intense and fractious, but even these have been positive in one way or another. Even in some of the most impassioned debates, people have been civil and have tended to focus on the points being made, rather than resorting to personal insults. Inevitably, such encounters have ended with an agreement to disagree and a mutual well-wishing from each party. To my mind, the point of such arguments is not to change anyone’s mind – the chance of being successful on a platform like Twitter is miniscule – but to allow parties of differing political persuasions and opinions to understand why someone might think differently to them.

While I don’t doubt that there is a problem with some people swaddling themselves in the safety of their carefully constructed echo-chamber, this hasn’t been my experience. Brexiters and Trump supporters regularly respond to, and challenge, things that I have written – and I’m always pleased when they do. For my part, I try very hard to stick to a few simple rules that include: never passing comment on personal features and traits, and never ridiculing people for spelling and grammatical errors. Although, my biggest weakness, I have to admit, is a tendency for sarcasm. I am frequently sarcastic on Twitter – much more than I am in ‘real life’ – but I do think it serves a useful purpose. I try not to be sarcastic about the things detailed above; instead, I usually use sarcasm to highlight, what I think, is a logical error in someone’s argument or just to try and be humorous about something frivolous. What the former often achieves is the provocation of a response, in a way that blandly pointing out a perceived mistake rarely does, meaning that the issues can then be discussed in greater detail.

Of course a large part of Twitter activity doesn’t involve abuse, or politically infused arguments; most of it consists of superficial attempts to provide stimulation of the neurological pleasure receptors:

Post something that you hope is interesting or funny.

Receive a ‘like’.

Experience an instant, but short lived feeling of satisfaction (or not, if your post doesn’t get any response at all).

Despite this apparently shallow cycle, Twitter (and the wider world of internet communication) can be, and frequently is, the source of meaningful personal encounters and opportunities that might not otherwise be possible. In the spring of last year, I was struggling to find the motivation I needed to finish an assignment. I was reading the news, making repeated trips to the cupboard for snacks, listening to music, staring into space and, naturally, checking Twitter. As part of this particularly long bout of procrastination I constructed and posted some frivolous tweets – hoping, of course, for another short-lived hit of dopamine. One such Tweet was a comment on my current efforts of procrastination alongside a wish to obtain just a small portion of – Art Historian, Oxford University lecturer, author, TV presenter and enthusiastic Tweeter – Dr. Janina Ramirez’s – apparently (as anyone who follows her work will know) endless levels of energy. These kinds of Tweets rarely get any response at all, so I was surprised when Janina replied. Although it was a small gesture I was struck by the kindness of it. I wasn’t commenting on something she was trying to sell, and she didn’t need to respond; I was quite happy throwing Tweets into the, usually unresponsive, abyss. Instead, I received my sought-after hit and also enjoyed a fresh wave of motivation, with which I was able to complete the assignment (for which I received my highest mark of the previous few years).

Anyway, to take a sharpened cleaver to a rather long story, this simple sharing of Tweets led to my attending the wonderful Gloucester History Festival, where I was able to chat with Janina, who is the President of the festival, along with some of her supporters and friends – a few of whom I had briefly communicated with on Twitter before. One of the  main things that struck, and surprised, me about this experience was how easy it was to speak to those people I had met previously on Twitter. Although I don’t avoid crowds (I quite enjoy them), I don’t usually feel very comfortable meeting a lot of new people and can be perfectly happy staying in the background, either on my own or with a small group of friends. On this occasion, however, the joy of meeting people who I’d only known online, and getting on well with them, was quite emotional and even a little overwhelming. Since then I regularly converse with the people I met there, and now consider them (Janina included) to be friends. That such meaningful relationships are possible from relatively flippant tweets is a wonder, and stands firmly in opposition to the characterisation of social media as a vacuous and futile cesspit.

main things that struck, and surprised, me about this experience was how easy it was to speak to those people I had met previously on Twitter. Although I don’t avoid crowds (I quite enjoy them), I don’t usually feel very comfortable meeting a lot of new people and can be perfectly happy staying in the background, either on my own or with a small group of friends. On this occasion, however, the joy of meeting people who I’d only known online, and getting on well with them, was quite emotional and even a little overwhelming. Since then I regularly converse with the people I met there, and now consider them (Janina included) to be friends. That such meaningful relationships are possible from relatively flippant tweets is a wonder, and stands firmly in opposition to the characterisation of social media as a vacuous and futile cesspit.

My very involvement with the Middle Way Society, and the friendships I’ve made within it, were also made possible through online communication. If I hadn’t become involved in a debate about the definition of religion on an online forum several years ago then I wouldn’t be writing this, and nor would I have subsequently had so many wonderful opportunities. My experience of meeting founding members Robert and Barry (at what I thought was a Secular Buddhist UK retreat, but was in fact a kind of committee meeting for a soon-to-be-no-more organisation), was similar to the one I later had in Gloucester. We’d all been involved in several discussions on the aforementioned forum and, on eventually meeting in person, we seemed to know each other better than I had expected. Robert, Barry and Peter (who I met at the same time online, but later in person) quickly became dear friends. Following the ensuing foundation of the Middle Way Society, I was asked if I’d like to join, which – after some hesitation (I’ve always been wary of becoming part of a ‘group’) – I agreed to do, as well as agreeing to become a member of the committee. This has meant I’ve been able to push myself and achieve things that I never thought I would – like writing blogs, for instance.

seemed to know each other better than I had expected. Robert, Barry and Peter (who I met at the same time online, but later in person) quickly became dear friends. Following the ensuing foundation of the Middle Way Society, I was asked if I’d like to join, which – after some hesitation (I’ve always been wary of becoming part of a ‘group’) – I agreed to do, as well as agreeing to become a member of the committee. This has meant I’ve been able to push myself and achieve things that I never thought I would – like writing blogs, for instance.

There are many problems with Twitter (and social media in general), but there are also many positives. We are still learning how to use this relatively new form of interaction; we are still immature and naïve. Even so, I feel confident that we’ll learn how to make use of social media with more maturity and care than we currently do. Part  of the problem is that this new frontier of communication gives the illusion that we are not dealing with embodied human beings, but lines of text generated from an abstract source. This has the effect of reducing our sense of social responsibility and shielding users from the effects that they have on others. Social conventions and restrictions can, when implemented wisely, serve as cohesive and stabilising forces. These have yet to develop fully, or effectively, in cyberspace and it remains difficult to predict what form they will eventually take, but I nonetheless believe that things will get better. By highlighting and encouraging that which is beneficial, as well as highlighting and challenging that which is harmful, we can begin to negotiate a Middle Way between the extremes of an imagined online utopia on the one hand and an online world that is categorised as a threat to society itself on the other.

of the problem is that this new frontier of communication gives the illusion that we are not dealing with embodied human beings, but lines of text generated from an abstract source. This has the effect of reducing our sense of social responsibility and shielding users from the effects that they have on others. Social conventions and restrictions can, when implemented wisely, serve as cohesive and stabilising forces. These have yet to develop fully, or effectively, in cyberspace and it remains difficult to predict what form they will eventually take, but I nonetheless believe that things will get better. By highlighting and encouraging that which is beneficial, as well as highlighting and challenging that which is harmful, we can begin to negotiate a Middle Way between the extremes of an imagined online utopia on the one hand and an online world that is categorised as a threat to society itself on the other.

You can hear our 2016 podcast about public shaming on social media with, journalist and author, Jon Ronson here.

If you are, or know someone who is, experiencing online abuse then these links provide advice of what you can do:

http://www.stoponlineabuse.org.uk/

https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/bjp8ma/expert-advice-on-how-to-deal-with-online-harassment

All pictures courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and licenced for reuse.

The MWS Podcast 135: Anthony McCann on the Garaiocht Manifesto

We’re joined this week by the creative and versatile polymath Anthony McCann. As a keynote speaker, after-dinner speaker, consultant, coach, trainer, and facilitator, he inspires people to reimagine and redesign their relationships, working environments, and communities through a better understanding of proximity, power, and possibility in their lives.

His work is based on 20 years of original research and teaching across the humanities and social sciences, and also of practitioner experience in leadership, community development, and performing arts. He’s here to talk to us today about ‘The Garaiocht Manifesto’ . More an invitation than a message. When it comes to professional life, trust your humanity. The Manifesto offers a human-scale and humane set of principles for sustaining the heart of being human in the art of being human in professional life.