To point out the likely consequences of a course of action usually seems like a helpful thing to do: for example, discouraging your friend from making themselves ill by drinking, or considering how much the recipient will really value the gift you are preparing. However, there are some cases where appealing to a particular consequence is a form of distraction or manipulation. Perhaps the consequence is frightening or flattering, but not nearly as important or probable as it is being presented as being, but because we have had our minds focused on that consequence we miss more important factors. An appeal to consequences needs to be distinguished from merely alerting people to them as possibilities.

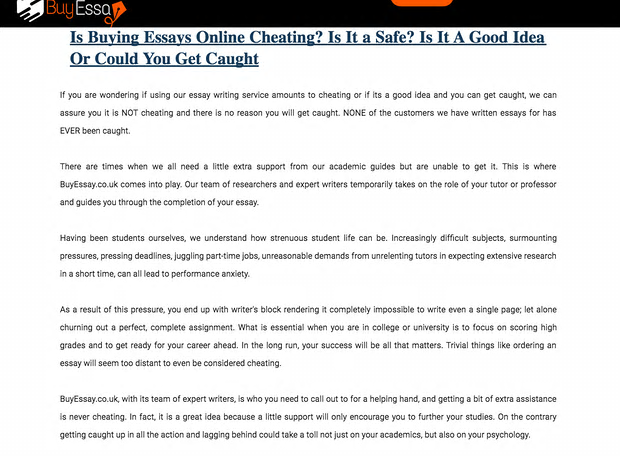

I came across a striking example recently in an article about ‘essay mill’ sites where students can pay to have essays written for them. This included the following clip from an essay mill site, in which its authors tried to persuade students of the morality of using it: This is quite cleverly done. The moral idea of cheating is ambiguously conflated with the idea of getting caught, so the unlikelihood of getting caught may well be confused with the justifiability of using the essay mill (even though the very idea of ‘getting caught’ implies cheating!). The student’s likely feelings are then sympathetically anticipated, making it more likely that the student will feel that the author understands their situation and can guide them wisely. But the clinching argument is where the appeal to consequences comes in: “In the long run, your success will be all that matters. Trivial things like ordering an essay will seem too distant to even be considered cheating”.

This is quite cleverly done. The moral idea of cheating is ambiguously conflated with the idea of getting caught, so the unlikelihood of getting caught may well be confused with the justifiability of using the essay mill (even though the very idea of ‘getting caught’ implies cheating!). The student’s likely feelings are then sympathetically anticipated, making it more likely that the student will feel that the author understands their situation and can guide them wisely. But the clinching argument is where the appeal to consequences comes in: “In the long run, your success will be all that matters. Trivial things like ordering an essay will seem too distant to even be considered cheating”.

“Your success will be all that matters” is a matter of the end justifying the means. In order to persuade the student of this, the author invites the student to think ahead to when they’ve got their qualification and succeeded in their goals, and the importance of those goals to them will doubtless outweigh every other consideration. This is an appeal to consequences because it invites us to assume that this consequence is necessarily the one that trumps all other considerations – in this case the normal social and academic rules about cheating. But just because it may contribute to the achievement of a goal that may be of great importance to you does not necessarily mean that this form of cheating is justified.

Another form of appeal to consequence is the type that seeks to persuade people to change beliefs that are justified by evidence because of the political, social, or economic benefits of doing so. Thus, for example, a climate change scientist might be appealed to by a politician or administrator distort their findings to follow an official anti-climate change line, despite the weight of evidence for climate change. At an extreme, this might amount to a form of blackmail (change your beliefs or you might lose your job) or bribery (change your beliefs and you’ll get promoted), which also involves an appeal to consequences. The reason that we should reject such appeals to change our beliefs about the ‘facts’, in my view, is not that the ‘facts’ are incontrovertible or that we do not at some level generally accept certain ‘facts’ because of the pragmatic consequences of doing so, but because from a wider and more integrated perspective the long-term consequences of supporting beliefs that fit the evidence better are far more important than the short-term reasons for rejecting them.

Why should the student resist the temptation to cheat? Not just because there are social rules against cheating, because those social rules are not necessarily correct just because they are social rules. Rather, because a more integrated perspective, in which the student remained fully in touch with a desire for integrity both in their own lives and in the academic system, should motivate the avoidance of cheating. A student tempted to cheat, or a climate change scientist tempted to abandon the integrity of their research for political reasons, might be better able to resist that temptation if they reflected on the situation not as just a conflict between social rules and individual inclination, or even between rival ‘facts’, but rather between different desires that they themselves possess – desires that can only be reconciled by taking the more integral and sustainable path. The alternative is not just a danger of being ‘caught’, but also a danger of long-term guilt and conflict.

The problem with appeals to consequences is thus the narrow absolutisation of the particular consequences that are being appealed to. The Middle Way, which asks us to return to the middle ground between positive and negative types of absolutisation, would point out that neither the social rules against cheating nor the rationalisations we might give for cheating are absolute. By freeing ourselves from both sets of extreme assumption, we are in a better position to make a judgement that is actually based on both evidence and values that are sustainable in the long-term.

Link to a list of other posts in the critical thinking series