The world is burning, burning, burning…. Yes, with greed, hatred and ignorance, as the Buddha pointed out about 2500 years ago in his ‘Fire Sermon’ (also found in T.S. Eliot’s ‘Wasteland’). But it is not just burning ‘metaphorically’. The world is burning quite literally. There are, or recently have been, wildfires in Greece, the US, Canada, Sweden, even Northern England… In 1997, massive fires in Indonesia added 40% to the world’s CO2 emissions. Such fires should add to anyone’s sense of urgency as regards climate change.

What the two kinds of fire have in common is that they are both part of closed feedback loops. The literal fires create more CO2, which adds to the Greenhouse Effect and Global Warming, desiccating the forests and creating more fires. The ‘metaphorical’ fires, on the other hand, burn in our reptilian brains: our striatum (craving) and amygdala (anxiety) create stress responses that interfere with our ability to understand and respond to the complex systemic problems known as ‘global warming’. The more stressed we feel, the more we reach desperately for shortcut absolutisations to contain it or dismiss it, the less adequate our response becomes, and the more we continue to behave in ways that exacerbate the situation – in turn increasing our stress. Runaway climate change could very easily happen inside people’s brains as well as in the world at large.

It is a feature of closed feedback loops that they tend to become ‘runaway’. The self-feeding causal loops create more and more of the same effect, taking us further and further away from any degree of equilibrium or stability. The ways in which the ecosystemic phenomena of the planet are getting caught up in these runaway loops is increasingly understood by those who pay any attention to climate change. We know that the melting ice caps reduce reflectivity of the sun’s radiation back into space, thus accelerating global warming. We also know that melting permafrost releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas that also accelerates the process. Both of these runaway loops are already well under way. We also know that higher CO2 levels acidify the oceans, which in turn reduces their ability to absorb carbon. Those are just the headlines of these complex ecosystemic loop effects. Many of them are well described in this excellent article by David Wallace-Wells.

But the runaway feedback loops are not limited to ecosystemic phenomena. They are also found in our psychological responses to them. Runaway feedback loops are particularly found in the mentally ill, the ideologically possessed, the addicted, the traumatised and the desperate. They are created by responses that our forebears probably developed to deal with short-term crisis situations that can only be resolved by rapid action, like fleeing a predator. But when the ‘predator’ keeps coming again and again without being decisively escaped, we replay the crisis response again and again in our heads. Our behaviour then turns to extremes, because we can only then act in shortcut, desperate ways. We may fight someone other than the source of danger because of a false association. We may deny that there is any danger present, or we may keep fleeing in the wrong direction. We will do anything as long as we feel we are doing something – anything but assessing and responding to the situation adequately. To do that we would have to understand more of its complexity and take long-term action. That would require a more balanced, stable, aware state of mind.

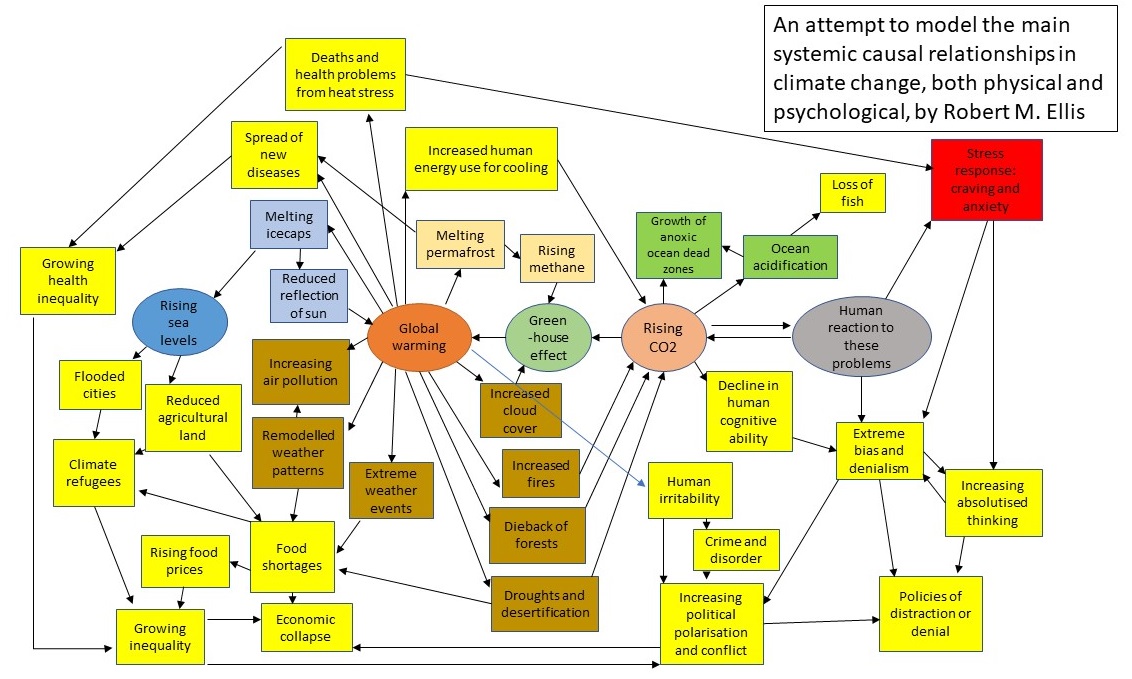

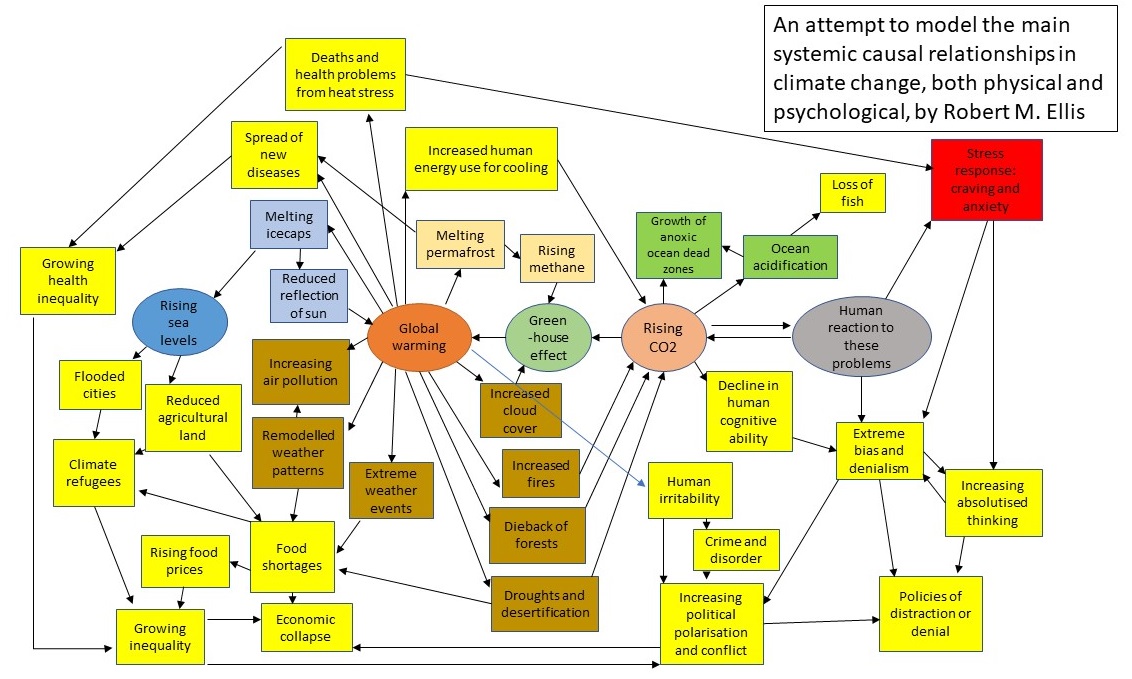

To understand global warming at all requires systemic thinking, in which we don’t restrict ourselves to one type of phenomenon or one way of studying it, but rather try to see all the processes in relation to each other (as far as we can). Nevertheless, many discussions of global warming seem to pay insufficient attention to the ways that the same feedback loops occur in our psychological responses to it. So, I have tried to combine the ecosystems with the psychosystems in this diagram. Like any attempt to represent a complex system, it is bound to leave a lot out. Even the phenomena mentioned will be related to each other in ways that aren’t represented by arrows, and then there will be lots of other phenomena involved that aren’t mentioned. But hopefully it is complex enough to show a variety of important closed feedback loop relationships (and related one-way causal effects), thus raising awareness, without being too complex to understand.

Whilst creating this diagram, I was reflecting on the ways that simply making this range of connections may be sufficient to understand the most important elements of the issue, without the necessity for detailed knowledge of exactly how strong any of these causal relationships are at any one point, or of the detailed evidence for that strength. Of course, that kind of knowledge is desirable, but perhaps the importance of acquiring it is often over-rated. If you focus too much on the evidence for one of these links (say, the causes and extent of the melting ice caps), you may end up building your entire response to global warming on that evidence (which may offer various potentials for disputed interpretation) and losing sight of the larger web of systemic connections that it is part of. However, even if you were to cut out the melting ice caps there are still plenty of other closed feedback loops at work, carrying the potential for serious runaway effects.

Simply understanding the systemic connections, and the ways in which these causal processes may operate to varying degrees, is enough to raise our awareness, when we realise how much many of them are mutually reinforcing. Many people, however, make the mistake of only thinking about some aspects of these mutually reinforcing loops whilst assuming that everything else will hold steady. This is particularly the case for the psychological (and thus political) effects. When we imagine humans responding to increasing climate change threats in the future, we tend to imagine humans living in the relatively stable, liberal world of Western democracy, where the more highly educated still have a fair amount of influence and there is still a fair degree of consensus between the educated and the powerful. What we need to take into account is that in all probability, the massive instability, widespread trauma, economic collapse and conflict that will be created by global warming will also massively degrade the capacity of human societies to make effective decisions in relation to it.

Central to recognising this is the relationship between absolutisation, bias, polarisation and stress responses that have been closely related to my interests in developing Middle Way Philosophy. The development of the mindfulness movement has made society increasingly aware of the negative effects of stress and the ways it can be counteracted, but not yet sufficiently of the ways that stress interacts with bias and polarisation, and there is very little awareness indeed that absolutisation can be recognised as a factor in all this. However, the more stressed we are, the more we are likely to rely on prefabricated mental shortcuts (absolutisations), rather than slowing down either for more careful conceptual thinking, or to take in more information, or to consider new models or ways of interpreting that information. Our current represented conceptual formulations are likely to be assumed to be enough, however limited the awareness on which they are based. Thus, at the very point when we face a crisis of unparalleled complexity, for which we need the maximum of awareness and reflectiveness, we are likely to start losing it. David Wallace-Wells points out that even the rise of CO2 levels itself directly degrades human cognitive capacity. Even those individuals who retain higher levels of awareness are likely to lose influence, when ever greater numbers of people in society as a whole are going into absolutising mode.

The most frightening thing is that this is no longer just a debatable prediction for the future – it’s happening already. That Brexit and Trump have occurred at the very point in human history when something resembling a halfway adequate worldwide political response to climate change had developed (in the shape of the Paris Agreement), can hardly be a coincidence. Brexit and Trump mark popular revolts against liberalism and the loss of identity and communal security it is perceived as bringing with it. These popular revolts, compared to the establishment consensus liberalism that they have usurped, are more strongly marked by heavy confirmation bias, single cause fallacies, straw men, ad hominem attacks and other such shortcuts. Whilst Brexit is wielded by neo-liberal ideologues who are prepared to use nationalism as a tool of influence, Trump is an endlessly manipulable pawn in the hands of similar ideologues in the US. The nuanced thinking of expert civil servants is being sidelined both in Washington and in London. This revolt is not yet primarily about climate change, but it is certainly directed against the liberal culture that was capable of doing something about climate change, and maintains the short-term interests of those with most to lose from its recognition – the rich. As such, it offers a foretaste of what is likely to follow when climate change strengthens, and when a collapse in food supply and the economy, coupled with increasingly extreme events, create greater panic.

As to when this will happen, it’s crucial to recall the properties of complex systems. Complex systems appear robust up to the point when they suddenly collapse, because their complexity gives them lots of adaptive options for new conditions. But each of these new adaptations adds more complexity and thus more vulnerability to any threat to the basic conditions that keep that whole system going. Thus, we can expect that when food scarcities arise from drought, flooding and other extreme weather events, the complex worldwide trading system will keep compensating by bringing food in from anywhere in the world, as well as finding new sources of food and more economical ways of producing it. However, that system can also suddenly collapse when there is no longer enough food to immediately support the people who maintain the trading systems. At that point, the inventiveness ceases and is replaced by desperate conflict over the remaining resources. When the system goes, it will go quite suddenly, along with all its inter-connecting dependent elements: food, economy, government, social support, security, basic trust and confidence. We may still have faith in that system until the moment it collapses.

The danger in writing in this vein is that this, also, may contribute to the very same closed feedback loops that the Middle Way is concerned with trying to avoid. When confronted by climate change, the most common response is denial of one kind or another – either theoretical denial or mere denial of practical responsibility. Much publicity about climate change often seems to accentuate this effect. On the other hand, it can also produce extreme positive responses. A friend of mine going back to childhood, Roger Hallam, has recently been involved in hunger striking against the third runway at Heathrow, and is now leading an ‘Extinction Rebellion’. Desperate times, we may feel, justify desperate measures. The trouble is that desperate measures are another form of shortcut – they simply do not work, because of the mental states they have to be pursued in. I greatly agree with everything Roger says about climate change, and even his assessment of the urgency of the situation, but I won’t be joining his rebellion.

By contrast, the Middle Way is not likely to work quickly enough, even if it was much more widely adopted. But the practice of the Middle Way depends on a more or less liberal political context, a tolerant society, and a weight of population that is both well-educated and secure. When we lose these, the chances of practising the Middle Way will become very slim indeed. Yet, despite this, as far as I can see, the Middle Way is our only hope. Extreme lunges tend to be based on rigid ideological assessments of the situation, or alternatively on a single-minded pursuit of the interests of a limited class. Their effect is to create more conflict and add further to our difficulties. Only the capacity to re-assess, adapt and persuade as we go along can possibly help us address this situation, and that depends on awareness, not rebellion. If the conditions for the practice of the Middle Way decay, all we can do is try to build them back up again.

Our sanity in the difficult times to come seems to me to be sustainable only by a feature of human brains that in other times has often served us ill: the shallow optimism of the left hemisphere. Even when Western civilisation is collapsing, we may still keep looking for the next opportunity round the corner. There is always hope, because, unless we are predisposed towards depression, hope is our default setting. It is not based on there being reasons enough for hope. At times, too, that hope may become more integrated, and we may reconnect with a basic contentment arising from our bodies. If we can slow or stop the closed feedback loop in our own brains, perhaps we will be able to live out our lives doing our best, however hopelessly, to maintain the earth.

Sources

There are many sources of information about climate change. David Wallace-Wells’ article, which was one of the catalysts for this one, has a fully referenced version. I’d suggest that his references offer a good place to start when checking on the factuality of any of the (widely accepted) factual assumptions about global warming in this article.

Many of the psychological elements here arise from my own work in Middle Way Philosophy. The relationship between absolutisation, biases and polarisation is particularly explored in Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief. This work synthesizes various other influences that are reviewed on this site, such as Iain McGilchrist’s ‘The Master and his Emissary’ and Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’. Paul Gilbert’s ‘The Compassionate Mind’ is a good source on the disruptive effects of the Reptilian brain and how they can be soothed.

On systems theory, I have also recently reviewed an excellent new introduction by Capra and Luisi. This includes some good material on ecosystems, but also puts these in the context of systems theory as a whole.

The diagram was created by me, and may be freely used by others for any educational purpose.

spects, though it also seems to slightly miss the point in some others.

spects, though it also seems to slightly miss the point in some others.