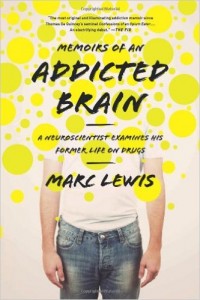

Memoirs of an addicted brain, by Marc Lewis (Public Affairs, 2013)

Reviewed by Robert M Ellis

Marc Lewis has had a seriously dodgy early life. After unhappy experiences at boarding school and joining the drugs party in late sixties Berkeley, he ends up frequenting an opium den in Calcutta and burgling Canadian medical facilities in search of drugs: before eventually making a complete recovery. The main purpose of this book is to tell that story, which it does in a highly absorbing fashion. What makes this book unusual, though, is the way that the memoir is punctuated by explanation of what was going on in his brain at the time. For most people, the orbito-frontal cortex, glutamates and dopamine receptors are not everyday fare: but, given how directly important these things are for all our experience at every moment, perhaps they should become so, and it is hard to imagine a presentation that would make them much more relevant and exciting than this one.

After reading Lewis’s later book, ‘The Biology of Desire’, I was rather expecting this earlier book to also have a particular angle on addiction and the brain to match the ‘addiction is not a disease’ subtitle of the later book. Although it combines anecdote and technical explanation in a similar way, though, I did not find such a strong thesis in these memoirs. Instead, whatever we learn about addiction from Lewis’s memoir is much more dependent on our own interpretation. I felt I learnt a good deal.

One thing I particularly got from this book is a deeper appreciation of the role of a lack of social acceptance in triggering addiction. Lewis stresses the role of natural opioids in our body’s system in providing us with a basic sense of contentment and self-acceptance. Because of the distancing of his parents and a negative response to the very competitive male environment in his boarding school, Lewis encountered depression early on because of this lack of opioids, and learnt to supply the warmth he needed to avoid it artificially by such drugs as heroin.

My interest in Lewis’s work to begin with was partly impelled by an interest in the relationship between addiction and dogma, and the two seem to have a close relationship here. Lewis shows how the dilemma of drug addiction often arose from the lack of any middle alternative between two extreme views of himself: either a negative view of himself, or a limitlessly positive one temporarily created by a flow of artificial opioids. To develop a Middle Way capacity, where he could make mistakes without descending into depression, he needed more support from his early conditioning than he received. If the young Lewis had not been in a position where he could so readily get hold of drugs, one can easily imagine him falling into, say, a religious cult instead, where the opioids would be natural ones arising from group acceptance, but the over-compensation just as extreme and rigid.

The way in which Lewis eventually recovers is also very interesting, though I felt that Lewis handled it more briefly than he might have done (compared to the detail given to his accounts of extreme self-torment in the final stages of his addiction, the account of his recovery seems rather rushed). However, we do get some detail on what seems to be a turning point.

I take a blank sheet of paper from my drawer and I draw a complex shape, somewhere between a flower and a mandala, around the word “No” in the centre of the page. Then I draw lines extending from that nexus to all the edges of the page. So that every bit of the paper is intersected by a line that leads back to the central “No”. I work on this for half an hour, embellishing it with elaborate designs that come without effort. My heart is beating slowly, steadily, with a sense of possibility. I dare not think about anything except the goal: to say no all day, every day, every moment it’s needed. No is my friend. No can be my centre. I finally look at my work and a slight smile comes to me. That smile is another taste of warmth. That smile soothes me and begins to strengthen me, and I tell myself, Yes, you can do it. You can say no. it’s only you who has to be convinced. (p.295)

Read superficially, this might seem to add justification for the “just say no” brigade. However, read and reflect more carefully and it seems clear that Lewis is doing a lot more than just saying ‘no’. In fact, in more profound ways he is saying ‘Yes’ – ‘yes, you can say no’. The intuitive work that goes into the mandala design seems crucial in creating the conditions for the integrative moment that finally occurs here, and that we come to recognise at the mention of warmth: that Lewis has a positive emotional investment in the alternatives to drugs. Those alternatives indicate that he is finally responding to his problems creatively.

It is at this point that Lewis seems to find a Middle Way between the extremes that have been oppressing him throughout his life up to that point: a Middle Way dependent on the provisionality of considering more than two opposed options. The conditions that allowed that new option to happen are surely complex, which is why I would have liked to know a bit more about them than he tells. Crucially, though, it is clear that some sort of alternative is emerging in his life at this time. His academic success, leading ultimately to professorship, comes after his recovery is under way, but I wondered how much that success, with its attendant social reassurance, contributed in the long-term to his avoidance of relapse.

I highly recommend this book, as a gripping read, an account of a spiritual breakthrough, and a source of understanding for how we get into extreme states. It’s treatment of the brain is entirely complementary to its treatment of direct experience, and gives you a vivid picture of their interrelationship

I’ll finish with Lewis’s own account of the central message of his book, given in his epilogue. Again, this puts me very much in mind of the close relationship between addiction and absolutisation. One could say what he says about addiction here about almost any dogma that afflicts us, from absolutised neo-liberalism to Islamic fundamentalism to fixed views of oneself.

But if there’s a central lesson to be learned, perhaps it’s this: The brain’s condensation of value is an error. Addiction is a neural mistake, a distortion, and attempted shortcut to get more of what you need by condensing “what you need” into a single, monolithic symbol. The drug (or other substance) stands for a cluster of needs: in my case, needs for warmth, safety, freedom, and self-sufficiency. Then it becomes too valuable, and you cannot live without it. But one thing cannot be all things. And that’s why, in the long run, addictions do such a lousy job of fulfilling needs – if they fulfil them at all. At the same time, many addictions, and certainly addictions to drugs, dash real opportunities to fulfil those needs elsewhere. (p.305)